(Press-News.org) MADISON — A promising therapy that treats blood cancers by harnessing the power of the immune system to target and destroy cancer cells could now treat solid tumors more efficiently. Thanks to a recent study published in Molecular Therapy – Methods & Clinical Development from Dan Cappabianca and Krishanu Saha at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can be improved by altering the conditions the T cells are grown in. And it was all discovered by chance.

T cells are white blood cells crucial for the immune system’s response to infections and cancer. They can be modified with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology to express a specific receptor that redirects their natural “killing instincts” toward targeting cancer cells, specifically those in tumors. T cells can "remember" a pathogen after first exposure, allowing a quicker and stronger response if encountered again, like how vaccines train the immune system to recognize and fight off specific pathogens.

But for the cells to be used as a robust cancer treatment, they must be made in specific conditions in the lab.

"We were comparing two distinct T-cell media formulations with varying nutrient levels," explains Cappabianca. "Interestingly, our breakthrough came entirely by chance. I inadvertently placed the cells in the wrong medium, which unexpectedly became the focal point of my entire thesis!"

In the body, T cells develop from stem cells in the bone marrow. In the lab, researchers activate the T cells in a nutrient-deficient medium with low concentrations of glucose and glutamine which the cells need for energy. Then they move them to a high-nutrient medium. The first step stresses the cells and triggers specific processes that can enhance their ability to target tumors, promote the formation of T memory cells, and select the more resilient cells that can survive with such low levels of energy. The second step supports rapid growth and T cell multiplication.

The result of this “metabolic priming” was that treated cells retained their stem cell-like qualities, thus enhancing their ability to kill cancer cells, transform into durable memory cells, and survive longer in the body.

"We discovered that by briefly restricting sugar exposure, akin to a three-day 'keto diet,' our T cells showed reduced maturity at the end of the manufacturing process. The less mature they are when reinfused into a patient, the longer they live fighting cancer," says Cappabianca.

The two-step process also appeared to help with cell memory. In CAR T-cell therapy, boosting these memory properties helps T cells better recognize and combat cancer over time.

In recent studies using T cells grown with the lab’s new approach, 63% of patients experienced a partial or complete reduction in tumors for a time. That’s an improvement from clinical trials using CAR T cells that were not grown with the lab’s two-step process where just 15% of patients experienced a partial or complete reduction in tumors after treatment.

More research is needed to understand the key factors that help these CAR T cells live longer and become effective against solid tumors. Looking ahead, researchers hope that this process of “metabolically priming” these specific kinds of CAR T cells can be adapted for large-scale manufacturing with the ultimate goal of treating patients within the next few years.

“A famous aphorism by French chemist, Louis Pasteur is that ‘chance favors only the prepared mind,’” says Saha. “Our unplanned media switch — really by chance — led us on a new path of discovery.”

–Laura RedEagle

END

Serendipity reveals new method to fight cancer with T cells

2024-07-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Financial incentives double smoking cessation rate for people with socioeconomic challenges

2024-07-02

OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLA. – A study published today by a University of Oklahoma researcher shows that financial incentives can make a big difference in helping smokers quit. The study found that when people with low socioeconomic staus are offered small financial incentives to stop smoking (in addition to receiving counseling and pharmacotherapy, primarily nicotine replacement therapy), they achieve higher quit rates, with some measures doubling the quit rates, when compared to study participants who received the same treatments without incentives. This finding is particularly important because adults with socioeconomic challanges ...

Biomolecular condensate ‘molecular putty’ properties found encoded in protein sequence

2024-07-02

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – July 2, 2024) Biomolecular condensates are membraneless hubs of condensed proteins and nucleic acids within cells, which researchers are realizing are tied to an increasing number of cellular processes and diseases. Studies of biomolecular condensate formation have uncovered layers of complexity, including their ability to behave like a viscoelastic material. However, the molecular basis for this putty-like property was unknown. Through a multi-institution collaboration, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists examined the interaction networks within condensates ...

New MSU study finds systematic biases at play in clinical trials

2024-07-02

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Randomized controlled trials, or RCTs, are believed to be the best way to study the safety and efficacy of new treatments in clinical research. However, a recent study from Michigan State University found that people of color and white women are significantly underrepresented in RCTs due to systematic biases.

The study, published in the Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, reviewed 18 RCTs conducted over the last 15 years that tested treatments for post-traumatic stress and alcohol use disorder. The researchers ...

Nuclear spectroscopy breakthrough could rewrite the fundamental constants of nature

2024-07-02

Key takeaways

Raising the energy state of an atom’s nucleus using a laser, or exciting it, would enable development of the most accurate atomic clocks ever to exist. This has been hard to do because electrons, which surround the nucleus, react easily with light, increasing the amount of light needed to reach the nucleus.

By causing the electrons to bond with fluorine in a transparent crystal, UCLA physicists have finally succeeded in exciting the neutrons in a thorium atom’s nucleus using a moderate amount of laser light.

This accomplishment means that measurements of time, gravity and other fields that are currently performed ...

Groundbreaking University of Alberta study discovers connection between between heart and brain in KBG syndrome

2024-07-02

EDMONTON — A new groundbreaking study sheds light on a medical question scientists have long wondered: why do 40 per cent of children with the rare neurodevelopmental disorder KBG syndrome have heart defects? The research now points to a critical link between the heart and the brain.

KBG syndrome can cause unusual facial development, skeletal abnormalities, intellectual underdevelopment and heart defects. The syndrome is caused by mutations in the ANKRD11 gene, which plays a crucial role in brain development, but it wasn’t until now ...

Optoelectronics gain spin control from chiral perovskites and III-V semiconductors

2024-07-02

A research effort led by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has made advances that could enable a broader range of currently unimagined optoelectronic devices.

The researchers, whose previous innovation included incorporating a perovskite layer that allowed the creation of a new type of polarized light-emitting diode (LED) that emits spin-controlled photons at room temperature without the use of magnetic fields or ferromagnetic contacts, now have gone a step further by integrating a III-V semiconductor ...

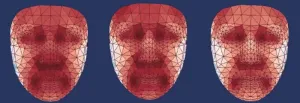

Doctors could soon use facial temperature for early diagnosis of metabolic diseases

2024-07-02

A colder nose and warmer cheeks may be a telltale sign of rising blood pressure.

Researchers discovered that temperatures in different face regions are associated with various chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and high blood pressure. These temperature differences are not easily perceptible by one’s own touch but can instead be identified using specific AI-derived spatial temperature patterns that require a thermal camera and a data-trained model. The results appear July 2 in the journal Cell Metabolism. With ...

Engineered plasma cells show long-lasting antileukemic activity in mice

2024-07-02

Researchers show for the first time that engineered human plasma B cells can be used to treat a disease—specifically leukemia—in a humanized animal model. The results mark a key step in the realization of ePCs as therapies to treat cancer, auto-immune disorders, and protein deficiency disorders. The results appear July 2 in the journal Molecular Therapy.

“We hope that this proof-of-concept study is the first of many applications of engineered plasma B cells, and eventually will lead to a single-shot therapeutic,” says senior study author Richard James (@ScienceRicker) of the Seattle Children’s ...

Proteins and fats can drive insulin production for some, paving way for tailored nutrition

2024-07-02

When it comes to managing blood sugar levels, most people think about counting carbs. But new research from the University of British Columbia shows that, for some, it may be just as important to consider the proteins and fats in their diet.

The study, published today in Cell Metabolism, is the first large-scale comparison of how different people produce insulin in response to each of the three macronutrients: carbohydrates (glucose), proteins (amino acids) and fats (fatty acids).

The findings reveal that production of the blood sugar-regulating hormone insulin is much more dynamic and individualized than previously ...

Melting of Alaskan glaciers accelerating faster than previously thought

2024-07-02

Melting of glaciers in a major Alaskan icefield has accelerated and could reach an irreversible tipping point earlier than previously thought, new research suggests.

The research, led by scientists at Newcastle University, UK, found that glacier loss on Juneau Icefield, which straddles the boundary between Alaska and British Columbia, Canada, has increased dramatically since 2010.

The team, which also included universities in the UK, USA and Europe, looked at records going back to 1770 and identified three distinct periods in how icefield volume changed. They saw that glacier volume loss remained fairly ...