(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Angelman syndrome is a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the maternally-inherited UBE3A gene and characterized by poor muscle control, limited speech, epilepsy, and intellectual disabilities. Though there isn't a cure for the condition, new research at the UNC School of Medicine is setting the stage for one.

Ben Philpot, PhD, the Kenan Distinguished Professor of Cell Biology and Physiology at the UNC School of Medicine and associate director of the UNC Neuroscience Center, and his lab have identified a small molecule that could be safe, non-invasively delivered, and capable of “turning on” the dormant paternally-inherited UBE3A gene copy brain-wide, which would lead to proper protein and cell function, amounting to a kind of gene therapy for individuals with Angelman syndrome.

“This compound we identified has shown to have excellent uptake in the developing brains of animal models,” said Philpot, who is a leading expert on Angelman syndrome. “We still have a lot of work to do before we could start a clinical trial, but this small molecule provides an excellent starting point for developing a safe and effective treatment for Angelman syndrome.”

But these results, which were published in Nature Communications, mark a major milestone in the field, according to Mark Zylka, W.R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of Cell Biology and Physiology at the UNC School of Medicine and Director of the UNC Neuroscience Center. No other small molecule compound has yet to show such promise for Angelman, he added.

Unlike other single-gene disorders such as cystic fibrosis and sickle-cell anemia, Angelman syndrome has a unique genetic profile. Researchers have found that children with the conditions are missing the maternally-inherited copy of the UBE3A gene, while the paternally-inherited copy of the UBE3A gene remains dormant in neurons, as it does in neurotypical individuals. Typically, UBE3A helps regulate the levels of important proteins; missing a working copy leads to severe disruptions in brain development.

For reasons that aren’t fully clear, the paternal copy of UBE3A is normally “turned off” in neurons throughout the entire brain. Thus, when the maternal copy of the UBE3A gene is mutated, this leads to a loss of UBE3A protein in the brain. Philpot and other researchers have theorized that turning on the paternal copy of UBE3A could help treat the condition.

Hanna Vihma, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Philpot lab and first author on the study, and colleagues screened more than 2,800 small molecules from a Pfizer chemogenetic library to determine if one could potently turn on paternal UBE3A in mouse models with Angelman syndrome.

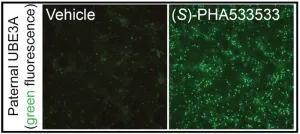

Researchers genetically modified mouse neural cells with a fluorescent protein that glows when the paternal UBE3A gene is turned on. After treating the neurons with more than 2,800 small molecules for 72 hours, researchers compared their thousands of treated cells against those treated with topotecan, a known small molecule that can turn on paternal UBE3A but lacked therapeutic value in animal models of the condition.

(S)-PHA533533, a compound that was previously developed as an anti-tumor agent, caused neurons to express a fluorescent glow that rivaled that induced by topotecan, meaning that its effect was potent enough to successfully turn on paternal UBE3A. Researchers were able to confirm the same results using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from humans with Angelman syndrome, indicating that this compound has clinical potential.

Additionally, researchers observed that (S)-PHA533533 has excellent bioavailability in the developing brain, meaning it travels to its target with ease and sticks around. This is notable in that previous genetic therapies for Angelman syndrome have had more limited bioavailability.

“We previously showed that topotecan, a topoisomerase inhibitor, had very poor bioavailability in mouse models,” said Vihma. “We were able to show that (S)-PHA533533 had better uptake and that the same small molecule could be translated in human-derived neural cells, which is a huge finding. It means it, or a similar compound, has true potential as a treatment for children.”

Although (S)-PHA533533 shows promise, researchers are still working to identify the precise target inside cells that causes the desired effects of the drug. Philpot and colleagues also need to conduct further studies to refine the medicinal chemistry of the drug to ensure that the compound – or another version of it – is safe and effective for future use in the clinical setting.

“This is unlikely to be the exact compound we would take forward to the clinic,” said Philpot. Along with medicinal chemists in the lab of Jeff Aubé, PhD, the Philpot lab is working to identify similar molecules with improved drug properties and safety profiles. “However, this gives us a compound that we can work with to create an even better compound that could be moved forward to the clinic.”

This work was supported by the Angelman Syndrome Foundation, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Simons Foundation, a sponsored research agreement between the University of North Carolina and Pfizer (to BDP), and Pinnacle Hill, LLC, a portfolio company of certain funds managed by Deerfield Management Company, L.P (to BDP).

END

UNC researchers identify potential treatment for Angelman syndrome

2024-07-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study: Weaker ocean circulation could enhance CO2 buildup in the atmosphere

2024-07-08

As climate change advances, the ocean’s overturning circulation is predicted to weaken substantially. With such a slowdown, scientists estimate the ocean will pull down less carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. However, a slower circulation should also dredge up less carbon from the deep ocean that would otherwise be released back into the atmosphere. On balance, the ocean should maintain its role in reducing carbon emissions from the atmosphere, if at a slower pace.

However, a new study by an MIT researcher finds that scientists may have to rethink the relationship between the ocean’s circulation and its ...

Brain size riddle solved as humans exceed evolution trend

2024-07-08

The largest animals do not have proportionally bigger brains - with humans bucking this trend - a new study published in Nature Ecology and Evolution has revealed.

Researchers at the University of Reading and Durham University collected an enormous dataset of brain and body sizes from around 1,500 species to clarify centuries of controversy surrounding brain size evolution.

Bigger brains relative to body size are linked to intelligence, sociality, and behavioural complexity – with humans having evolved exceptionally large brains. The new research, published today (Monday, 8 July), reveals the largest animals do not have proportionally bigger brains, ...

GeneMAP discovery platform will help define functions for ‘orphan’ metabolic proteins

2024-07-08

A multidisciplinary research team has developed a discovery platform to probe the function of genes involved in metabolism — the sum of all life-sustaining chemical reactions.

The investigators used the new platform, called GeneMAP (Gene-Metabolite Association Prediction), to identify a gene necessary for mitochondrial choline transport. The resource and derived findings were published July 8 in the journal Nature Genetics.

“We sought to gain insight into a fundamental question: ‘How does genetic variation determine our “chemical individuality” — the inherited differences that make us biochemically unique?” said Eric Gamazon, ...

Zero-emissions trucks alone won't cut it: Early retirement of polluters key to California's emission goals

2024-07-08

California must implement early retirement for existing heavy-duty vehicles as well as introducing zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs) to protect Black, Latino and vulnerable communities and hit net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions targets by 2045. This is the outcome of a new study published in Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability by researchers from Stanford University and Arizona State University.

Stringent policies for mandating both ZEVs and early vehicle retirement could reduce cumulative emissions by two-thirds (64%) and reduce half of pollution-related mortality, particularly among disadvantaged communities.

California is the world’s 5th largest ...

Hexagonal perovskite oxides: Electrolytes for next-generation protonic ceramic fuel cells

2024-07-08

This study presents a significant advancement in fuel cell technology. Researchers from Tokyo Tech identified hexagonal perovskite-related Ba5R2Al2SnO13 oxides (R = rare earth metal) as materials with exceptionally high proton conductivity and thermal stability. Their unique crystal structure and large number of oxygen vacancies enable full hydration and high proton diffusion, making these materials ideal candidates as electrolytes for next-generation protonic ceramic fuel cells that can operate at intermediate temperatures without degradation.

Fuel cells offer a promising solution for clean energy by combining hydrogen and oxygen to generate electricity, ...

Genomic data integration improves prediction accuracy of apple fruit traits!

2024-07-08

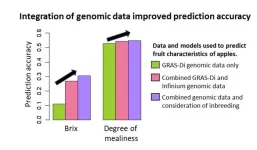

Over the past few decades, the world has witnessed tremendous progress in the tools used for genomic analysis. While it’s usually more common to associate these tools with the fields of biology and medicine, they have proven to be very valuable in agriculture as well. Using numerous DNA markers obtained from next-generation sequencing technologies, breeders can make genomic predictions and select promising individuals based on based on their predicted trait values.

Various systems and methodologies aimed at improving the ...

Visualizing short-lived intermediate compounds produced during chemical reactions

2024-07-08

Immobilizing small synthetic molecules inside protein crystals proves to be a promising avenue for studying intermediate compounds formed during chemical reactions, report scientists from Tokyo Tech. By integrating this method with time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography, they successfully visualized reaction dynamics and rapid structural changes occurring within reaction centers immobilized inside protein crystals. This innovative strategy holds significant potential for the intelligent design of drugs, catalysts, and functional materials.

Most complex chemical reactions, whether synthetic or biological, do not involve ...

It’s time to rethink our attitude to fatness, academic argues

2024-07-08

Prejudice against fat people is endemic in our society and public health initiatives aimed at reducing obesity have only worsened the problem, according to a U.S. academic.

In her new book Why It’s OK To Be Fat, Rekha Nath, an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Alabama, argues for a paradigm shift in how society approaches fatness.

According to Nath, society must stop approaching fatness as a trait to rid the population of, and instead fatness should be approached through the lens of social equality, attending to the systematic ways that society penalizes fat people for their body size.

Nath explains: “Being fat is seen as unattractive, as gross even. ...

Braiding community values with science is key to ecosystem restoration

2024-07-08

Up on the “roof of the world”, one of the world’s largest ecosystem restoration projects is taking place. The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP) in western China is the world’s highest plateau and covers a land area roughly five times the size of France.

Home to thousands of rare plants and wildlife and the source of water for more than 2.5 billion people, this vital ecosystem is under threat.

The region’s grassland is degrading due to climate change and intense livestock grazing. Government ...

Study of key characteristics of politicians reveals ‘ambition, narcissism, genuine idealism’ among common traits

2024-07-08

In a new study of politicians’ personalities, humour, charm and raw courage are listed among the most important character traits for successful leaders.

Bill Jones, Honorary Professor of Political Studies at Liverpool Hope University, has combed through biographies and interviewed key political figures to understand the kind of people who enter politics, and strengths and frailties of those who occupy positions of power.

Jones explains: “Why do aspiring politicians embark on such a perilous journey, involving hugely long hours, no real job security and, on occasions, high degrees ...