(Press-News.org) Some people lose weight slower than others after workouts, and a Kobe University research team found a reason. They studied what happens to mice that cannot produce signal molecules that respond specifically to short-term exercise and regulate the body’s energy metabolism. These mice consume less oxygen during workouts, burn less fat and are thus also more susceptible to gaining weight. Since the team found this connection also in humans, the newly gained knowledge of this mechanism might provide a pathway for treating obesity.

It is well known that exercise leads to the burning of fat. But for some people, this is much more difficult than for others, casting doubt on whether the mechanism behind losing or gaining weight is as simple as “calories in minus calories out.” Researchers have previously identified a signal molecule, a protein by the name of “PGC-1⍺,” that seems to link exercise and its effects. However, whether an increased amount of this protein actually leads to these effects or not has been inconclusive, since some experiments suggested it while others didn’t. More recently, the Kobe University endocrinologist OGAWA Wataru as well as other researchers found that there are actually a few different versions of this protein. Ogawa explains: “These new PGC-1α versions, called “b” and “c,” have almost the same function as the conventional “a” version, but they are produced in muscles more than tenfold more during exercise, while the a version does not show such an increase.” His team therefore set out to prove the idea that it is the newly discovered versions, and not the previously known one, that regulate the energy metabolism during workouts.

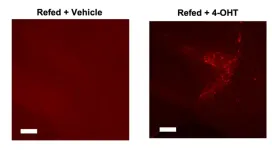

To do so, the researchers created mice that lack the b and c versions of the signal molecule PGC-1⍺ while they still have the standard a version, and measured the mice’s muscle growth, fat burning and oxygen consumption during rest and short-term as well as long-term workout. They also recruited human test subjects with and without type 2 diabetes and submitted them to similar tests as the mice, because insulin-intolerant and obese people are known to have reduced levels of the signal molecule.

Ogawa and his team published their results in the journal Molecular Metabolism. They found that, while all versions of the signal molecule cause similar biological reactions, their different levels of production have far-reaching consequences for the organism’s health. The lack of the alternative b and c versions of PGC-1⍺ means that the organism is essentially blind to short-term activity and does not adapt to these stimuli, with the effect that such individuals consume less oxygen and burn less fat during and after workouts. In humans, the research team found that the more the test subjects produced the b and c versions of the signal molecule, the more they consumed oxygen and the less percent body fat they had, across healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes. “Thus, the hypothesis that the genes in skeletal muscle determine susceptibility to obesity was correct,” summarizes Ogawa these findings. However, they also found that long-term exercise stimulates the production of the standard a version of PGC-1⍺, and mice that exercised regularly over the course of six weeks exhibited an increase in muscle mass irrespective of whether they could produce the alternative versions of the signal molecule or not.

In addition to the production in muscles, the Kobe University team looked at how the production of the different versions of PGC-1⍺ changes in fat tissues, and found no relevant effect in response to exercise. However, since animals also burn fat to maintain body temperature, the researchers also investigated the mice’s ability to tolerate cold. And indeed, they found that the production of the b and c versions of the signal molecule in brown adipose tissue is increased when the animals are exposed to cold, and that the body temperature of individuals that cannot produce these versions dropped significantly under these conditions. On the one hand, this may contribute to these individuals’ having more body fat, but on the other hand it seems to imply that the b and c versions of the signal molecule may be responsible for metabolic adaptations to short-term stimuli more generally.

Ogawa and his team point out that understanding the physiological activity of the different versions of PGC-1⍺ might allow to devise treatment approaches for obesity: “Recently, anti-obesity drugs that suppress appetite have been developed and are increasingly prescribed in many countries around the world. However, there are no drugs that treat obesity by increasing energy expenditure. If a substance that increases the b and c versions can be found, this could lead to the development of drugs that enhance energy expenditure during exercise or even without exercise. Such drugs could potentially treat obesity independently of dietary restrictions.” The team are now conducting research to find out more about the mechanisms that lead to the increased production of the signal molecule’s b and c versions during exercise.

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grants 26461337, 16H01391 and 15H04848). It was conducted in collaboration with researchers from Tokushima University, the Karolinska Institutet, Kyoto University, Gunma University, the National Defense Academy, Nippon Medical School, the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research and Asahi Life Foundation.

Kobe University is a national university with roots dating back to the Kobe Commercial School founded in 1902. It is now one of Japan’s leading comprehensive research universities with nearly 16,000 students and nearly 1,700 faculty in 10 faculties and schools and 15 graduate schools. Combining the social and natural sciences to cultivate leaders with an interdisciplinary perspective, Kobe University creates knowledge and fosters innovation to address society’s challenges.

END

Same workout, different weight loss: Signal molecule versions are key

2024-07-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Trained peers are as effective as clinical social workers in reducing opioid overdose, new trial finds

2024-07-11

In Rhode Island, USA, over one in four emergency department (ED) patients at high risk of overdose has a non-fatal opioid overdose in the 18 months post-discharge. A parallel, two-arm, randomized controlled trial conducted in Rhode Island of over 600 ED patients at high risk of opioid overdose found that support from a peer recovery support specialist (a trained support worker with lived experience of addiction) was as effective in reducing opioid overdose as support from a licensed clinical social worker. In other words, interviewing and intervention techniques informed by lived ...

Study: Algorithms used by universities to predict student success may be racially biased

2024-07-11

Washington, July 11, 2024—Predictive algorithms commonly used by colleges and universities to determine whether students will be successful may be racially biased against Black and Hispanic students, according to new research published today in AERA Open, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association. The study—conducted by Denisa Gándara (University of Texas at Austin), Hadis Anahideh (University of Illinois Chicago), Matthew Ison (Northern Illinois University), and Lorenzo Picchiarini (University of Illinois Chicago)—found ...

Comprehensive evaluation of large language models in mining gene relations and pathway knowledge

2024-07-11

Understanding complex biological pathways, such as gene-gene interactions and gene regulatory networks, is crucial for exploring disease mechanisms and advancing drug development. However, manual literature curation of these pathways cannot keep pace with the exponential growth of discoveries. Large-scale language models (LLMs) trained on extensive text corpora contain rich biological information and can be leveraged as a biological knowledge graph for pathway curation.

Recently, Quantitative Biology published a study titled "A Comprehensive ...

Researchers pinpoint brain cells that delay first bite of food

2024-07-11

LA JOLLA, CA—Do you grab a fork and take a first bite of cake, or say no and walk away? Our motivation to eat is driven by a complex web of cells in the brain that use signals from within the body, as well as sensory information about the food in front of us, to determine our behaviors. Now, Scripps Research scientists have identified a group of neurons in a small and understudied region of the brain—the parasubthalamic nucleus (PSTN)—that controls when an animal decides to take a first bite of food.

In the study, published in Molecular Psychiatry on July 4, 2024, the team of scientists set out to selectively manipulate a group of PSTN cells that dial up their ...

With spin centers, quantum computing takes a step forward

2024-07-11

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Quantum computing, which uses the laws of quantum mechanics, can solve pressing problems in a broad range of fields, from medicine to machine learning, that are too complex for classical computers. Quantum simulators are devices made of interacting quantum units that can be programmed to simulate complex models of the physical world. Scientists can then obtain information about these models, and, by extension, about the real world, by varying the interactions in a controlled way and measuring the resulting behavior of the quantum simulators.

In a paper published in Physical Review B, a UC Riverside-led research team ...

Scientists release new research on planted mangroves’ ability to store carbon

2024-07-11

U.S. Forest Service ecologists and partners published new findings on how planted mangroves can store up to 70% of carbon stock to that found in intact stands after only 20 years.

Researchers have long known that mangroves are superstars of carbon absorption and storage. But until now, limited information existed on how long it took for carbon stored in planted mangroves to reach levels found in intact mangroves.

“About ten years ago, Sahadev Sharma, then with the Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, and I discovered that 20-year-old mangrove plantations in Cambodia had carbon stocks comparable to those of intact forests,” ...

New immune cell therapy benefits laboratory models of ALS and has some positive results in an individual with the disease

2024-07-11

Immune system dysregulation and elevated inflammation contribute to the development of the fatal neurodegenerative condition amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.

In new research published in The FASEB Journal, repeated infusions of certain immune cells delayed ALS onset and extended survival in mice, and also reduced markers of inflammation in an individual with the disease. The work was conducted by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General ...

Trial of cell-based therapy for high-risk lymphoma leads to FDA breakthrough designation

2024-07-11

CAR-T cell therapy, which targets a specific protein on the surface of cancer cells, causes tumors to shrink or disappear in about half of patients with large B-cell lymphoma who haven’t experienced improvement with chemotherapy treatments.

But if this CAR-T treatment fails, or the cancer returns yet again — as happens in approximately half of people — the prognosis is dire. The median survival time after relapse is about six months.

Now, a phase 1 clinical trial at Stanford Medicine ...

Major trial looks at most effective speech therapy for people with Parkinson’s disease

2024-07-11

A major clinical trial, led by experts at the University of Nottingham, has shown the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD®) is more effective than the current speech and language therapy provided by the NHS, when treating patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD).

The results of the NIHR HTA funded trial, which are published today in the BMJ, showed that LSVT LOUD® was more effective at reducing the participant’s reported impact of voice problems than no speech and language therapy, as well as the NHS delivered speech and language therapy.

The trial was led by experts from the Universities of Nottingham and Birmingham, ...

Intensive voice treatment more effective than NHS speech therapy for Parkinson’s disease

2024-07-11

An intensive voice treatment developed in the USA and known as the Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT LOUD) is more effective than conventional NHS speech and language therapy or no therapy for people with Parkinson’s disease, finds a trial published in The BMJ today.

The researchers say the results emphasise the need to optimise the use of speech and language therapy resources for people with Parkinson’s disease.

Slurred or slow speech (known as dysarthria) is a common feature of Parkinson’s disease and can have a significant effect ...