(Press-News.org) Engineers at the University of California San Diego have trained a humanoid robot to effortlessly learn and perform a variety of expressive movements, including simple dance routines and gestures like waving, high-fiving and hugging, all while maintaining a steady gait on diverse terrains.

The enhanced expressiveness and agility of this humanoid robot pave the way for improving human-robot interactions in settings such as factory assembly lines, hospitals and homes, where robots could safely operate alongside humans or even replace them in hazardous environments like laboratories or disaster sites.

“Through expressive and more human-like body motions, we aim to build trust and showcase the potential for robots to co-exist in harmony with humans,” said Xiaolong Wang, a professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. “We are working to help reshape public perceptions of robots as friendly and collaborative rather than terrifying like The Terminator.”

Wang and his team will present their work at the 2024 Robotics: Science and Systems Conference, which will take place from July 15 to 19 in Delft, Netherlands.

What makes this humanoid robot so expressive is that it is trained on a diverse array of human body motions, enabling it to generalize new motions and mimic them with ease. Much like a quick-learning dance student, the robot can swiftly learn new routines and gestures.

To train their robot, the team used an extensive collection of motion capture data and dance videos. Their technique involved training the upper and lower body separately. This approach allowed the robot’s upper body to replicate various reference motions, such as dancing and high-fiving, while its legs focused on a steady stepping motion to maintain balance and traverse different terrains.

“The main goal here is to show the ability of the robot to do different things while it’s walking from place to place without falling,” said Wang.

Despite the separate training of the upper and lower body, the robot operates under a unified policy that governs its entire structure. This coordinated policy ensures that the robot can perform complex upper body gestures while walking steadily on surfaces like gravel, dirt, wood chips, grass and inclined concrete paths.

Simulations were first conducted on a virtual humanoid robot and then transferred to a real robot. The robot demonstrated the ability to execute both learned and new movements in real-world conditions.

Currently, the robot’s movements are directed by a human operator using a game controller, which dictates its speed, direction and specific motions. The team envisions a future version equipped with a camera to enable the robot to perform tasks and navigate terrains all autonomously.

The team is now focused on refining the robot’s design to tackle more intricate and fine-grained tasks. “By extending the capabilities of the upper body, we can expand the range of motions and gestures the robot can perform,” said Wang.

Paper title: “Expressive Whole-Body Control for Humanoid Robots.” Co-authors include Xuxin Cheng*, Yandong Ji*, Junming Chen and Ruihan Yang, UC San Diego; and Ge Yang, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

END

Learning dance moves could help humanoid robots work better with humans

2024-07-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Women and social exclusion: The complicated nature of rejection and retaliation

2024-07-11

New research from the University of Ottawa (uOttawa) has provided a complicated glance into young women’s responses to interpersonal conflict, with retaliation often the answer to rejection and perceived social exclusion by other females.

The study, published in Nature’s Scientific Reports, highlights the complicated nature of women’s interpersonal relationships by examining the stress arising from rejection, and if the personal characteristics of those imposing the rejection influences ...

Immunotherapy approach shows potential in some people with metastatic solid tumors

2024-07-11

Early findings from a small clinical trial provide evidence that a new cellular immunotherapy approach may be effective in treating metastatic solid tumors. In the trial, researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) genetically engineered normal white blood cells, known as lymphocytes, from each patient to produce receptors that recognize and attack their specific cancer cells. These initial findings are from people with metastatic colorectal cancer who had already undergone multiple earlier treatments. The personalized immunotherapy shrank tumors in several patients and was able to keep the tumors from regrowing for up to seven months. ...

Neighborhood impact on children's well-being shifted during COVID-19 pandemic, ECHO study suggests

2024-07-11

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted daily life and has raised concerns about its impact on children’s well-being. A new study from the NIH Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes Program (ECHO) sheds light on how a neighborhood’s physical and social environment influenced a child’s well-being before and during the pandemic.

According to an analysis of ECHO Cohort data, the neighborhood environment was less likely to be associated with child well-being during the ...

Neurobiologist Sung Soo Kim receives 2024 Scholar Award from McKnight Foundation

2024-07-11

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Birds migrating. Your cat, returning home from a day of roaming. Bees taking pollen to their hives. You, finding yourself back home without actually remembering the drive from work. Animal navigation is a fundamental behavior, so innate that most of the time we don’t notice that we’re doing it. And yet, so many times a day we (and the animals around us) unerringly find our ways to our target locations whether they be old haunts or new venues, from different directions and even in the dark.

How do we do it? That’s the question UC Santa Barbara neurobiologist Sung Soo Kim seeks to ...

Charting an equitable future for DNA and ancient DNA research in Africa

2024-07-11

CLEVELAND AND NAIROBI — July 11, 2024 — Today, the American Journal of Human Genetics published a perspective piece on the need for an equitable and inclusive future for DNA and ancient DNA (aDNA) research in Africa. The paper, coauthored by an international team of 36 scientists from Africa, North America, Asia, Australia, and Europe, was led by Dr. Elizabeth (Ebeth) Sawchuk of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and Dr. Kendra Sirak of Harvard University.

DNA from ancient and living African peoples is critical for researchers studying our species’ evolution and population ...

Introducing co-cultures: When co-habiting animal species share culture

2024-07-11

Cooperative hunting, resource sharing, and using the same signals to communicate the same information—these are all examples of cultural sharing that have been observed between distinct animal species. In an opinion piece published June 19 in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution, researchers introduce the term “co-culture” to describe cultural sharing between animal species. These relationships are mutual and go beyond one species watching and mimicking another species’ behavior—in co-cultures, both species influence each other in substantial ways.

“Co-culture challenges the notion ...

Study finds health risks in switching ships from diesel to ammonia fuel

2024-07-11

As container ships the size of city blocks cross the oceans to deliver cargo, their huge diesel engines emit large quantities of air pollutants that drive climate change and have human health impacts. It has been estimated that maritime shipping accounts for almost 3 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions and the industry’s negative impacts on air quality cause about 100,000 premature deaths each year.

Decarbonizing shipping to reduce these detrimental effects is a goal of the International Maritime Organization, ...

Seeing inside Alzheimer’s disease brain

2024-07-11

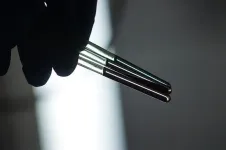

Scientists investigating Alzheimer’s disease have determined the structure of molecules within a human brain for the very first time.

Published today in Nature, the study describes how scientists used cryo-electron tomography, guided by fluorescence microscopy, to explore deep inside an Alzheimer’s disease donor brain.

This gave 3-dimensional maps in which they could observe proteins, the molecular building blocks of life a million-times smaller than a grain of rice, within the brain.

The study zoomed in on two proteins that cause dementia– ‘β-amyloid’, a protein that forms microscopic ...

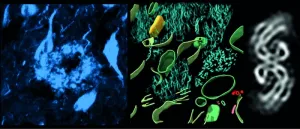

Nanoplastics and ‘forever chemicals’ disrupt molecular structures, functionality

2024-07-11

EL PASO, Texas (July 11, 2024) – Researchers at The University of Texas at El Paso have made significant inroads in understanding how nanoplastics and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — commonly known as forever chemicals — disrupt biomolecular structure and function. The work shows that the compounds can alter proteins found in human breast milk and infant formulas — potentially causing developmental issues downstream.

Nanoplastics and forever chemicals are manmade compounds present throughout the environment; a series of recent studies have linked them to numerous ...

Quadrupolar nuclei measured for the first time by zero-field NMR

2024-07-11

What is the structure of a particular molecule? And how do molecules interact with each other? Researchers interested in those questions frequently use nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to find answers. In NMR, a powerful external magnetic field is employed to align the spins of atomic nuclei, which are then induced to rotate by an oscillating weak magnetic field generated by coils. A change in voltage as a result can be converted to measurable frequencies. Based on this, researchers can identify the molecular structures while also revealing ...