(Press-News.org) Scientists at the University of Sydney and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine have made a remarkable discovery: a commonly used blood thinner, heparin, can be repurposed as an inexpensive antidote for cobra venom.

Cobras kill thousands of people a year worldwide and perhaps a hundred thousand more are seriously maimed by necrosis – the death of body tissue and cells – caused by the venom, which can lead to amputation.

Current antivenom treatment is expensive and does not effectively treat the necrosis of the flesh where the bite occurs.

“Our discovery could drastically reduce the terrible injuries from necrosis caused by cobra bites – and it might also slow the venom, which could improve survival rates,” said Professor Greg Neely, a corresponding author of the study from the Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Science at the University of Sydney.

Using CRISPR gene-editing technology to identify ways to block cobra venom, the team, which consisted of scientists based in Australia, Canada, Costa Rica and the UK, successfully repurposed heparin (a common blood thinner) and related drugs and showed they can stop the necrosis caused by cobra bites.

The research is published today on the front cover of Science Translational Medicine.

PhD student and lead author, Tian Du, also from the University of Sydney, said: “Heparin is inexpensive, ubiquitous and a World Health Organization-listed Essential Medicine. After successful human trials, it could be rolled out relatively quickly to become a cheap, safe and effective drug for treating cobra bites.”

The team used CRISPR to find the human genes that cobra venom needs to cause necrosis that kills the flesh around the bite. One of the required venom targets are enzymes needed to produce the related molecules heparan and heparin, which many human and animal cells produce. Heparan is on the cell surface and heparin is released during an immune response. Their similar structure means the venom can bind to both. The team used this knowledge to make an antidote that can stop necrosis in human cells and mice.

Unlike current antivenoms for cobra bites, which are 19th century technologies, the heparinoid drugs act as a ‘decoy’ antidote. By flooding the bite site with ‘decoy’ heparin sulfate or related heparinoid molecules, the antidote can bind to and neutralise the toxins within the venom that cause tissue damage.

Joint corresponding author, Professor Nicholas Casewell, Head of the Centre for Snakebite Research & Interventions at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, said: “Snakebites remain the deadliest of the neglected tropical diseases, with its burden landing overwhelmingly on rural communities in low- and middle-income countries.

“Our findings are exciting because current antivenoms are largely ineffective against severe local envenoming, which involves painful progressive swelling, blistering and/or tissue necrosis around the bite site. This can lead to loss of limb function, amputation and lifelong disability.”

Snakebites kill up to 138,000 people a year, with 400,000 more experiencing long-term consequences of the bite. While the number affected by cobras is unclear, in some parts of India and Africa, cobra species account for most snakebite incidents.

The World Health Organization has identified snakebite as a priority in its program for tackling neglected tropical diseases. It has announced an ambitious goal of reducing the global burden of snakebite in half by 2030.

Professor Neely said: “That target is just five years away now. We hope that the new cobra antidote we found can assist in the global fight to reduce death and injury from snakebite in some of the world’s poorest communities.”

Working in the Dr John and Anne Chong Laboratory for Functional Genomics at the Charles Perkins Centre, Professor Neely’s team takes a systematic approach to finding drugs to treat deadly or painful venoms. It does this using CRISPR to identify the genetic targets used by a venom or toxin inside humans and other mammals. It then uses this knowledge to design ways to block this interaction and ideally protect people from the deadly actions of these venoms.

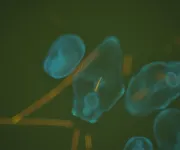

This approach was used to identify an antidote to box jellyfish venom by the team in 2019.

Professor Casewell leads the Centre for Snakebite Research & Interventions at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM). The centre has conducted a diverse portfolio of research activities to better understand the biology of snake venoms and improve the efficacy, safety and affordability of antivenom treatment for tropical snakebite victims for more than 50 years. It boasts some of the world's leading snakebite experts and has access to LSTM’s herpetarium, the largest and most diverse collection of tropical venomous snakes in the UK.

DOWNLOAD videos, images and photos of snakes and researchers at this link.

INTERVIEWS

Professor Greg Neely | greg.neely@sydney.edu.au | +61 403 227 100

[NB: Professor Neely is currently in Canada, so please consider timezones]

Professor Nicholas Casewell | nicholas.casewell@lstmed.ac.uk | +44 151 702 9329

PhD student and lead author Tian Du | tian.du@sydney.edu.au

MEDIA ENQUIRIES

Sydney: Marcus Strom | marcus.strom@sydney.edu.au | +61 474 269 459

Liverpool: Dominic Smith | dominic.smith@lstmed.ac.uk | +44 7469 105 025

RESEARCH

Du, T. et al, ‘Molecular dissection of cobra venom highlights heparinoids as an effective snakebite antidote’. (Science Translational Medicine, 2024) DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adk4802

DECLARATION

Greg Neely, Nicholas Casewell, Felicity Chung and Tian Du declare that a provisional patent application has been submitted based on these results. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Research funding was received from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), the Australian Research Council, the Royal Society, the Wellcome Trust and UK Medical Research Council.

Thanks to Dr John and Anne Chong for ongoing funding of the Chong Laboratory for Functional Genomics at the University of Sydney.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All testing using animal models was conducted with the approval of the relevant ethics committees in the United Kingdom and Costa Rica. No animal testing occurred in Australia.

END

New antidote for cobra bites discovered

Cheap, available drug could help reduce impact of snakebites worldwide

2024-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ant insights lead to robot navigation breakthrough

2024-07-17

Have you ever wondered how insects are able to go so far beyond their home and still find their way? The answer to this question is not only relevant to biology but also to making the AI for tiny, autonomous robots. TU Delft drone-researchers felt inspired by biological findings on how ants visually recognize their environment and combine it with counting their steps in order to get safely back home. They have used these insights to create an insect-inspired autonomous navigation strategy for tiny, lightweight robots. The strategy allows such robots to come back home after long trajectories, while requiring extremely little computation and memory (0.65 kiloByte per ...

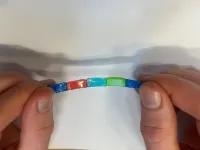

Soft, stretchy ‘jelly batteries’ inspired by electric eels

2024-07-17

Researchers have developed soft, stretchable ‘jelly batteries’ that could be used for wearable devices or soft robotics, or even implanted in the brain to deliver drugs or treat conditions such as epilepsy.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, took their inspiration from electric eels, which stun their prey with modified muscle cells called electrocytes.

Like electrocytes, the jelly-like materials developed by the Cambridge researchers have a layered structure, like sticky Lego, that makes them capable of delivering an electric current.

The self-healing jelly batteries can stretch ...

The most endangered fish are the least studied

2024-07-17

The most threatened reef fishes are also the most overlooked by scientists and the general public. That is the startling finding of a team of scientists led by a CNRS researcher.1 In a study to be published in Science Advances on July 17, they measured the level of human interest in 2,408 species of marine reef fish and found that the attention of the scientific community is attracted by the commercial value more than the ecological value of the fishes. The public, on the other hand, is primarily influenced by the aesthetic characteristics of certain species, such as the red lionfish ...

Mindfulness training may lead to altered states of consciousness, study finds

2024-07-17

Mindfulness training may lead participants to experience disembodiment and unity – so-called altered states of consciousness – according to a new study from researchers at the University of Cambridge.

The team say that while these experiences can be very positive, that is not always the case. Mindfulness teachers and students need to be aware that they can be a side-effect of training, and students should feel empowered to share their experiences with their teacher or doctor if they have any concerns.

Mindfulness-based programmes have ...

New technique pinpoints nanoscale ‘hot spots’ in electronics to improve their longevity

2024-07-17

When electronic devices like laptops or smartphones overheat, they are fundamentally suffering from a nanoscale heat transfer problem. Pinpointing the source of that problem can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

“The building blocks of our modern electronics are transistors with nanoscale features, so to understand which parts of overheating, the first step is to get a detailed temperature map,” says Andrea Pickel, an assistant professor from the University of Rochester’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. “But you need something with nanoscale ...

Study shows ancient viruses fuel modern-day cancers

2024-07-17

Peek inside the human genome and, among the 20,000 or so genes that serve as building blocks of life, you’ll also find flecks of DNA left behind by viruses that infected primate ancestors tens of millions of years ago.

These ancient hitchhikers, known as endogenous retroviruses, were long considered inert or ‘junk’ DNA, defanged of any ability to do damage. New CU Boulder research published July 17 in the journal Science Advances shows that, when reawakened, they can play a critical role in helping cancer survive and thrive. The study also suggests that silencing certain endogenous retroviruses can make cancer treatments work better.

“Our study shows that diseases ...

Reef pest feasts on 'sea sawdust'

2024-07-17

Researchers have uncovered an under-the-sea phenomenon where coral-destroying crown-of-thorns starfish larvae have been feasting on blue-green algae bacteria known as ‘sea sawdust’.

The team of marine scientists from The University of Queensland and Southern Cross University found crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) larvae grow and thrive when raised on an exclusive diet of Trichodesmium – a bacteria that often floats on the ocean’s surface in large slicks.

UQ’s Dr Benjamin Mos from the School ...

Mental health training for line managers linked to better business performance, says new study

2024-07-17

Mental health training for line managers is strongly linked to better business performance, and it could save companies millions of pounds in lost sick days every year, according to new research led by experts at the University of Nottingham.

The results of the study, which are published in PLOS ONE, showed a strong association between mental health training for line managers and improved staff recruitment and retention, better customer service, and lower levels of long-term mental health sickness absence.

The study was led by Professor Holly Blake from the School of Health Sciences at the University of Nottingham and Dr Juliet Hassard of Queen’s ...

Diatom surprise could rewrite the global carbon cycle

2024-07-17

When it comes to diatoms that live in the ocean, new research suggests that photosynthesis is not the only strategy for accumulating carbon. Instead, these single-celled plankton are also building biomass by feeding directly on organic carbon in wide swaths of the ocean. These new findings could lead researchers to reduce their estimate of how much carbon dioxide diatoms pull out of the air via photosynthesis, which in turn, could alter our understanding of the global carbon cycle, which is especially relevant given the changing climate.

This research is led by bioengineers, bioinformatics experts and other genomics researchers ...

Microbes found to destroy certain ‘forever chemicals’

2024-07-17

UC Riverside environmental engineering team has discovered specific bacterial species that can destroy certain kinds of “forever chemicals,” a step further toward low-cost treatments of contaminated drinking water sources.

The microorganisms belong to the genus Acetobacterium and they are commonly found in wastewater environments throughout the world.

Forever chemicals, also known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS, are so named because they have stubbornly strong carbon-fluorine chemical bonds, which make them persistent in the environment.

The microorganisms discovered by UCR scientists and their collaborators ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

[Press-News.org] New antidote for cobra bites discoveredCheap, available drug could help reduce impact of snakebites worldwide