(Press-News.org) Tree bark surfaces play an important role in removing methane gas from the atmosphere, according to a study published today (24 July) in Nature.

While trees have long been known to benefit climate by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, this new research reveals a surprising additional climate benefit. Microbes hidden within tree bark can absorb methane – a powerful greenhouse gas – from the atmosphere.

An international team of researchers led by the University of Birmingham has shown for the first time that microbes living in bark or in the wood itself are removing atmospheric methane on a scale equal to or above that of soil. They calculate that this newly discovered process makes trees 10 per cent more beneficial for climate overall than previously thought.

Methane is responsible for around 30 per cent of global warming since pre-industrial times and emissions are currently rising faster than at any point since records began in the 1980s.

Although most methane is removed by processes in the atmosphere, soils are full of bacteria that absorb the gas and break it down for use as energy. Soil had been thought of as the only terrestrial sink for methane, but the researchers now show that trees may be as important, perhaps more so.

Lead researcher on the study, Professor Vincent Gauci of the University of Birmingham, said: “The main ways in which we consider the contribution of trees to the environment is through absorbing carbon dioxide through photosynthesis, and storing it as carbon. These results, however, show a remarkable new way in which trees provide a vital climate service.

“The Global Methane Pledge, launched in 2021 at the COP26 climate change summit aims to cut methane emissions by 30 per cent by the end of the decade. Our results suggest that planting more trees, and reducing deforestation surely must be important parts of any approach towards this goal.”

In the study, the researchers investigated upland tropical, temperate and boreal forest trees. Specifically, they took measurements spanning tropical forests in the Amazon and Panama; temperate broadleaf trees in Wytham Woods, in Oxfordshire, UK; and boreal coniferous forest in Sweden. The methane absorption was strongest in the tropical forests, probably because microbes thrive in the warm wet conditions found there. On average the newly discovered methane absorption adds around 10% to the climate benefit that temperate and tropical trees provide.

By studying methane exchange between the atmosphere and the tree bark at multiple heights, they were able to show that while at soil level the trees were likely to emit a small amount of methane, from a couple of metres up the direction of exchange switches and methane from the atmosphere is consumed.

In addition, the team used laser scanning methods to quantify the overall global forest tree bark surface area, with preliminary calculations indicating that the total global contribution of trees is between 24.6-49.9 Tg (millions of tonnes) of methane. This fills a big gap in understanding the global sources and sinks of methane.

The tree shape analysis also shows that if all the bark of all the trees of the world were laid at flat, the area would be equal to the Earth’s land surface. “Tree woody surfaces add a third dimension to the way life on Earth interacts with the atmosphere, and this third dimension is teeming with life, and with surprises”, said co-author Yadvinder Malhi of the University of Oxford.

Professor Gauci and colleagues at Birmingham are now planning a new research programme to find out if deforestation has led to increased atmospheric methane concentrations. They also aim to understand more about the microbes themselves, the mechanisms used to take up the methane and will investigate if this atmospheric methane removal by trees can be enhanced.

ENDS

For media enquiries, interviews, or an embargoed copy of the research paper, please contact Press Office, University of Birmingham, tel: +44 (0)121 4142772: email: pressoffice@contacts.bham.ac.uk

Notes to editor:

The University of Birmingham is ranked amongst the world’s top 100 institutions. Its work brings people from across the world to Birmingham, including researchers, teachers and more than 8,000 international students from over 150 countries.

Gauci at al. (2024). ‘Global atmospheric methane uptake by upland tree woody surfaces.’ Nature

END

Trees reveal climate surprise – bark removes methane from the atmosphere

2024-07-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Webb images nearest super-Jupiter, opening a new window to exoplanet research

2024-07-24

“We were excited when we realised we had imaged this new planet”, said Elisabeth Matthews, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. She is the main author of the underlying research article published in the journal Nature. “To our surprise, the bright spot that appeared in our MIRI images did not match the position we were expecting for the planet”, Matthews points out. “Previous studies had correctly identified a planet in this system but underestimated this super-Jupiter gas giant’s ...

Social vulnerability linked with mental health and substance use disorders

2024-07-24

A new study published in JAMA Psychiatry uncovers significant associations between social vulnerability — a measurement that aggregates social determinants of health like socioeconomic status, housing type, education and insurance coverage — and the prevalence and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders in the United States. The results have the potential to reshape public health policies to better serve systemically disadvantaged populations.

Powerful analysis of meaningful data

“We're continually learning that so much of healthcare — both mental health and physical health — is impacted by the environment ...

Insurance type and withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy in critically injured trauma patients

2024-07-24

About The Study: In this cohort study of U.S. adult trauma patients who were critically injured, patients who were uninsured underwent earlier withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy compared with those with private or Medicaid insurance. Based on the findings of this study, a patient’s ability to pay was likely associated with a shift in decision-making for withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy, suggesting the influence of socioeconomics on patient outcomes.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Graeme Hoit, M.D., email graeme.hoit@mail.utoronto.ca.

To ...

Physician posttraumatic stress disorder during COVID-19

2024-07-24

About The Study: The findings of this study suggest that physicians were more likely to experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Targeted interventions to support physician well-being during traumatic events like pandemics are required.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Manish M. Sood, M.D., email Msood@toh.on.ca.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23316)

Editor’s ...

Social isolation changes and long-term outcomes among older adults

2024-07-24

About The Study: Increased isolation was associated with elevated risks of mortality, disability, and dementia, irrespective of baseline isolation status in this cohort study. These results underscore the importance of interventions targeting the prevention of increased isolation among older adults to mitigate its adverse effects on mortality, as well as physical and cognitive function decline.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Judy Zhong, Ph.D., email judy.zhong@nyumc.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at ...

Under pressure: how cells respond to physical stress

2024-07-24

Cell membranes play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity and functionality of cells. However, the mechanisms by which they perform these roles are not yet fully understood. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), in collaboration with the Institut de biologie structurale de Grenoble (IBS) and the University of Fribourg (UNIFR), have used cryo-electron microscopy to observe how lipids and proteins at the plasma membrane interact and react to mechanical stress. This work shows that, depending on conditions, small membrane regions can stabilize ...

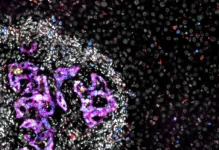

Preventing cancer cells from colonizing the liver

2024-07-24

In brief:

ETH Zurich researchers have discovered proteins on the surface of colorectal cancer cells and liver cells that bind together and that play a major role in the formation of new metastases.

The binding of the proteins triggers fundamental changes in colorectal cancer cells that allow them to take root in the liver.

These new findings will help to develop future treatments that may hinder the formation of often fatal metastases.

In cases where cancer is fatal, nine out of ten times the culprit is metastasis. This is when the primary tumour has sent out cells, like seeds, and invaded other organs of the body. While medicine has made great progress in treating primary tumours, ...

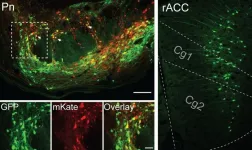

Neuroscientists discover brain circuitry of placebo effect for pain relief

2024-07-24

CHAPEL HILL, NC – The placebo effect is very real. This we’ve known for decades, as seen in real-life observations and the best double-blinded randomized clinical trials researchers have devised for many diseases and conditions, especially pain. And yet, how and why the placebo effect occurs has remained a mystery. Now, neuroscientists have discovered a key piece of the placebo effect puzzle.

Publishing in Nature, researchers at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine– with colleagues from Stanford, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and ...

'Gene misbehavior' widespread in healthy people

2024-07-24

Scientists have uncovered that ‘gene misbehaviour’ – where genes are active when they were expected to be switched off – is a surprisingly common phenomenon in the healthy human population.

The team also identify several mechanisms behind these gene activity errors. This may help inform precision medicine approaches and enable the development of targeted therapies to correct expression.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Cambridge and AstraZeneca studied the activity of inactive genes in a large, healthy population for the first time. While rare at the individual gene level, they revealed misexpression ...

Arc Institute welcomes first Scientific Advisory Board members; appoints two new members to Board of Directors

2024-07-24

Today, Arc Institute, the scientific research organization pioneering new models for scientific discovery and translation, is announcing the creation of its Scientific Advisory Board and its first two Scientific Advisors, as well as the appointment of two new members to the Arc Board of Directors.

New Scientific Advisory Board

Dr. Carolyn Bertozzi, Ph.D., and Dr. Aviv Regev, Ph.D., join as the first two members of Arc’s Scientific Advisory Board and will provide strategic guidance, share their ...