(Press-News.org) EVANSTON, Ill. --- One of just two vertebrates without a jaw, sea lampreys that are wreaking havoc in Midwestern fisheries are simultaneously helping scientists understand the origins of two important stem cells that drove the evolution of vertebrates.

Northwestern University biologists have pinpointed when the gene network that regulates these stem cells may have evolved and gained insights into what might be responsible for lampreys’ missing mandibles.

The two cell types — pluripotent blastula cells (or embryonic stem cells) and neural crest cells — are both “pluripotent,” which means they can become all other cell types in the body.

In a new paper, researchers compared lamprey genes to those of the Xenopus, a jawed aquatic frog. Using comparative transcriptomics, the study revealed a strikingly similar pluripotency gene network across jawless and jawed vertebrates, even at the level of transcript abundance for key regulatory factors.

But the researchers also discovered a key difference. While both species’ blastula cells express the pou5 gene, a key stem cell regulator, the gene is not expressed in neural crest stem cells in lampreys. Losing this factor may have limited the ability of neural crest cells to form cell types found in jawed vertebrates (animals with spines) that make up the head and jaw skeleton.

The study will be published July 26 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

By comparing the biology of jawless and jawed vertebrates, researchers can gain insight into the evolutionary origins of features that define vertebrate animals including humans, how differences in gene expression contribute to key differences in the body plan, and what the common ancestor of all vertebrates looked like.

“Lampreys may hold the key to understanding where we came from,” said Northwestern’s Carole LaBonne, who led the study. “In evolutionary biology, if you want to understand where a feature came from, you can't look forward to more complex vertebrates that have been evolving independently for 500 million years. You need to look backwards to whatever the most primitive version of the type of animal you're studying is, which leads us back to hagfish and lampreys — the last living examples of jawless vertebrates.”

An expert in developmental biology, LaBonne is a professor of molecular biosciences in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. She holds the Erastus Otis Haven Chair and is part of the leadership of the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) new Simons National Institute for Theory and Mathematics in Biology.

LaBonne and her colleagues previously demonstrated that the developmental origin of neural crest cells was linked to retaining the gene regulatory network that controls pluripotency in blastula stem cells. In the new study, they explored the evolutionary origin of the links between these two stem cell populations.

“Neural crest stem cells are like an evolutionary Lego set,” said LaBonne. “They become wildly different types of cells, including neurons and muscle, and what all those cell types have in common is a shared developmental origin within the neural crest.”

While blastula stage embryonic stem cells lose their pluripotency and become confined to distinct cell types fairly rapidly as an embryo develops, neural crest cells hold onto the molecular toolkit that controls pluripotency later into development.

LaBonne’s team found a completely intact pluripotency network within lamprey blastula cells, stem cells whose role within jawless vertebrates had been an open question. This implies that blastula and neural crest stem cell populations of jawed and jawless vertebrates co-evolved at the base of vertebrates.

Northwestern postdoctoral fellow and first author Joshua York observed “more similarities than differences" between the lamprey and Xenopus.

“While most of the genes controlling pluripotency are expressed in the lamprey neural crest, the expression of one of these key genes — pou5 — was lost from these cells,” York said. “Amazingly, even though pou5 isn’t expressed in a lamprey’s neural crest, it could promote neural crest formation when we expressed it in frogs, suggesting this gene is part of an ancient pluripotency network that was present in our earliest vertebrate ancestors.”

The experiment also helped them hypothesize that the gene was specifically lost in certain creatures, not something jawed vertebrates developed later on.

“Another remarkable finding of the study is that even though these animals are separated by 500 million years of evolution, there are stringent constraints on expression levels of genes needed to promote pluripotency.” LaBonne said. “The big unanswered question is, why?”

The paper was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01GM116538 and F32DE029113), the NSF (grant 1764421), the Simons Foundation (grant SFARI 597491-RWC) and the Walder Foundation through the Life Sciences Research Foundation. The study is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Joseph Walder.

END

Lampreys possess a ‘jaw-dropping’ evolutionary origin

Invasive, blood-sucking fish ‘may hold the key to understanding where we came from’

2024-07-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

"Just like your mother?" Maternal and paternal X-chromosomes show skewed distribution in different organs and tissues.

2024-07-26

A new study published in Nature Genetics by the Lymphoid Development Group at the MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences has reveals that the contribution of cells expressing maternal or paternal X chromosomes can be selectively skewed in different parts of the body. The study leverages human data from the 1000 Genomes Project combined with mouse models of human X chromosome-linked DNA sequence variation to advance our fundamental understanding of development in biologically female individuals who have two X chromosomes.

Until now, it was thought that the usage of maternal and paternal X-chromosomes was similar throughout the body. The ...

Conflicting health advice from agencies drives confusion, study finds, but doctors remain most trusted

2024-07-26

Distrust of health experts and credulity towards misinformation can kill. For example, during the Covid-19 crisis, high-profile health experts received death threats while misinformation went viral on social media. And already long before the pandemic, easily preventable but potentially serious diseases had been making a comeback around the world due to vaccine hesitancy – often powered by conspiracy theories.

But what feeds this lack in trust in reliable sources of health information? Can it perhaps be mitigated? Those are the subjects of a new study in Frontiers in Medicine by researchers from the US.

“Here we show that individuals who ...

Towards next-gen indoor lighting: novel tunable ultrasonic liquid crystal light diffuser

2024-07-26

It is no mystery that light is essential to human life. Since the discovery of fire, humans have developed various artificial light sources, such as incandescent lamps, gaslights, discharge lamps, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The distribution and intensity of artificial lights indoors are important factors that affect our ability to study and work effectively and influence our physical and mental health. Consequently, modern artificial light sources are designed with these psychological elements to achieve the best aesthetics. ...

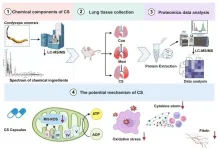

Chinese medicinal fungus shows promise in treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

2024-07-26

A recent study from China has reported that Cordyceps sinensis (CS), a traditional Chinese medicinal fungus, can ameliorate idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in mice by inhibiting mitochondrion-mediated oxidative stress. The research, conducted by a team led by Huan Tang and Jigang Wang from the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, was published in Wiley's MedComm-Future Medicine.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic and progressive lung disease characterized by a decline in lung function, ultimately leading to respiratory failure and a significantly reduced quality of life for patients. With a median ...

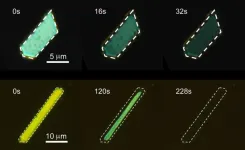

Shining light on similar crystals reveals photoreactions can differ

2024-07-26

A rose by any other name is a rose, but what of a crystal? Osaka Metropolitan University-led researchers have found that single crystals of four anthracene derivatives with different substituents react differently when irradiated with light, perhaps holding clues to how we can use such materials in functional ways.

Graduate student Sogo Kataoka, Dr. Daichi Kitagawa, a lecturer, and Professor Seiya Kobatake of the Graduate School of Engineering and colleagues compared the photoreactions of the single crystals when the entire anthracene crystal was irradiated with light.

For two ...

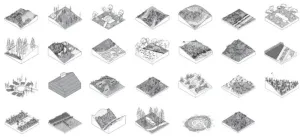

Innovative fire stewardship techniques to reshape landscape design to better adapt to and coexist with wildfire-prone environments

2024-07-26

Over the past few decades, many parts of the world have experienced record-breaking wildfire events—a trend that is, unfortunately, expected to rise. These extreme events not only result in mass evacuations, but also release greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, pose risks to life, devastate buildings and essential infrastructure, and fundamentally disrupt and detrimentally transform native ecosystems. In response to the increased risk of catastrophic wildfires, many planning and site design practices have sought to protect the trends and status quo of land development. These measures strive to resist and, ...

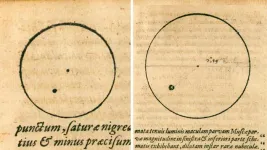

Kepler’s 1607 pioneering sunspot sketches solve solar mysteries 400 years later

2024-07-26

Using modern techniques, researchers have re-examined Johannes Kepler's half-forgotten sunspot drawings and revealed previously hidden information about the solar cycles before the grand solar minimum. By recreating the conditions of the great astronomer’s observations and applying Spörer's law in the light of modern statistics, an international collaborative group led by Nagoya University in Japan has measured the position of Kepler’s sunspot group, placing it at the tail-end of the solar cycle before the cycle that Thomas Harriot, Galileo Galilei, and other ...

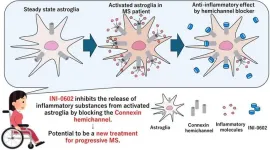

A new therapeutic target offers a promising pathway for multiple sclerosis treatment

2024-07-26

Fukuoka, Japan – Researchers from Kyushu University have identified a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of advanced multiple sclerosis (MS), a potentially disabling condition associated with the central nervous system. In their latest study, conducted using an experimental mouse model of MS, they explored the role of connexin 43 (Cx43), a protein involved in cellular communication and cardiac function, and examined whether targeting this protein with specific blockers could improve ...

Recent insights and advances in treatment and management show promise in stemming the growing prevalence of diabetes

2024-07-26

A new paper surveying advances in diabetes pathogenesis and treatment explores the complex factors contributing to the onset and progression of the disease, suggesting that an understanding of these dynamics is key to developing targeted interventions to reduce the risk of developing diabetes and managing its complications.

In a paper published July 25 in a special 50th anniversary issue of the peer-reviewed journal Cell, the authors surveyed hundreds of studies that have emerged over the years looking at the causes underpinning types 1 (T1D) and 2 (T2D) diabetes and new treatments for the disease. They examine the role that genes, environmental factors, and ...

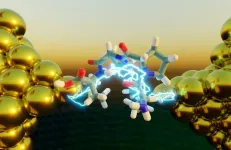

Folded peptides are more electrically conductive than unfolded peptides

2024-07-26

What puts the electronic pep in peptides? A folded structure, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Electron transport, the energy-generating process inside living cells that enables photosynthesis and respiration, is enhanced in peptides with a collapsed, folded structure. Interdisciplinary researchers at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology combined single-molecule experiments, molecular dynamics simulations and quantum mechanics to validate their findings.

“This discovery provides a new understanding of how electrons flow through peptides ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

[Press-News.org] Lampreys possess a ‘jaw-dropping’ evolutionary originInvasive, blood-sucking fish ‘may hold the key to understanding where we came from’