(Press-News.org) UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 19:00 BST / 14:00 ET THURSDAY 1 AUGUST 2024

Images available via link in the notes section

Exceptional fossils with preserved soft parts reveal that the earliest molluscs were flat, armoured slugs without shells.

The new species, Shishania aculeata was covered with hollow, organic, cone-shaped spines.

The fossils preserve exceptionally rare detailed features which reveal that these spines were produced using a sophisticated secretion system that is shared with annelids (earthworms and relatives).

A team of researchers including scientists from the University of Oxford have made an astonishing discovery of a new species of mollusc that lived 500 million years ago. The new fossil, called Shishania aculeata*, reveals that the most primitive molluscs were flat, shell-less slugs covered in a protective spiny armour. The findings have been published today in the journal Science.

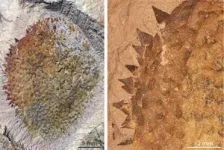

The new species was found in exceptionally well-preserved fossils from eastern Yunnan Province in southern China dating from a geological Period called the early Cambrian, approximately 514 million years ago. The specimens of Shishania are all only a few centimetres long and are covered in small spikey cones (sclerites) made of chitin, a material also found in the shells of modern crabs, insects, and some mushrooms.

Specimens that were preserved upside down show that the bottom of the animal was naked, with a muscular foot like that of a slug that Shishania would have used to creep around the seafloor over half a billion years ago. Unlike most molluscs, Shishania did not have a shell that covered its body, suggesting that it represents a very early stage in molluscan evolution.

Present-day molluscs have a dizzying array of forms, and include snails and clams and even highly intelligent groups such as squids and octopuses. This diversity of molluscs evolved very rapidly a long time ago, during an event known as the Cambrian Explosion, when all the major groups of animals were rapidly diversifying. This rapid period of evolutionary change means that few fossils have been left behind that chronicle the early evolution of molluscs.

Corresponding author Associate Professor Luke Parry, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, said: ‘Trying to unravel what the common ancestor of animals as different as a squid and oyster looked like is a major challenge for evolutionary biologists and palaeontologists – one that can’t be solved by studying only species alive today. Shishania gives us a unique view into a time in mollusc evolution for which we have very few fossils, informing us that the very earliest mollusc ancestors were armoured spiny slugs, prior to the evolution of the shells that we see in modern snails and clams.’

Because the body of Shishania was very soft and made of tissues that don’t typically preserve in the fossil record, the specimens were challenging to study, as many of the specimens were poorly preserved.

First author Guangxu Zhang, a recent PhD graduate from Yunnan University in China who discovered the specimens said: ‘At first I thought that the fossils, which were only about the size of my thumb, were not noticeable, but I saw under a magnifying glass that they seemed strange, spiny, and completely different from any other fossils that I had seen. I called it “the plastic bag” initially because it looks like a rotting little plastic bag. When I found more of these fossils and analysed them in the lab I realised that it was a mollusc.’

Associate Professor Parry added: ‘We found microscopic details inside the conical spines covering the body of Shishania that show how they were secreted in life. This sort of information is incredibly rare, even in exceptionally preserved fossils.’

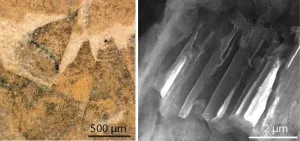

The spines of Shishania show an internal system of canals that are less than a hundredth of a millimetre in diameter. These features show that the cones were secreted at their base by microvilli, tiny protrusions of cells that increase surface area, such as in our intestines where they aid food absorption.

This method of secreting hard parts is akin to a natural 3D printer, allowing many invertebrate animals to secrete hard parts with huge variation of shape and function from providing defence to facilitating locomotion.

Hard spines and bristles are known in some present-day molluscs (such as chitons), but they are made of the mineral calcium carbonate rather than organic chitin as in Shishania. Similar organic chitinous bristles are found in more obscure groups of animals such as brachiopods and bryozoans, which together with molluscs and annelids (earthworms and their relatives) form the group Lophotrochozoa.

Professor Parry added: ‘Shishania tells us that the spines and spicules we see in chitons and aplacophoran molluscs today actually evolved from organic sclerites like those of annelids. These animals are very different from one another today and so fossils like Shishania tell us what they looked like deep in the past, soon after they had diverged from common ancestors.’

Co-author Jakob Vinther at the University of Bristol said: ‘Molluscs today are extraordinarily disparate and they diversified very quickly during the Cambrian Explosion, meaning that we struggle to piece together their early evolutionary history. We know that the common ancestor of all molluscs alive today would have had a single shell, and so Shishania tells us about a very early time in mollusc evolution before the evolution of a shell.’

Co-corresponding author Xiaoya Ma (Yunnan University and University of Exeter) said: ‘This new discovery highlights the treasure trove of early animal fossils that are preserved in the Cambrian rocks of Yunnan Province. Soft bodied molluscs have a very limited fossil record, and so these very rare discoveries tell us a great deal about these diverse animals.’

*Etymology of Shishania aculeata: Shishan refers to Shishan Zhang, for his outstanding contributions to the study of early Cambrian strata and fossils in eastern Yunnan; aculeata (Latin), having spines, prickly.

Notes:

For media enquiries and interview requests, contact Associate Professor Luke Parry luke.parry@seh.ox.ac.uk

Images relating to the study which can be used in articles can be found at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1eLiDU7bDWpVyxNJK9IzevPGL2ORud86n?usp=drive_link These images are for editorial purposes only and MUST be credited (see captions document in file). They MUST NOT be sold on to third parties.

The study ‘A Cambrian spiny stem mollusk and the deep homology of lophotrochozoan scleritomes’ will be published in the journal Science at 19:00 BST / 14:00 ET Thursday 1 August 2024 at www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ado0059 (link will go live when embargo lifts). To view a copy of the study before this, under embargo, contact the Science editorial team at scipak@aaas.org or see the Science press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak/

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the eighth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing £15.7 billion to the UK economy in 2018/19, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs.

END

Half a billion-year-old spiny slug reveals the origins of mollusks

2024-08-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Award-winning research maps the body’s internal sensory communication highway

2024-08-01

When the question is “how are you feeling on the inside?,” it’s our vagus nerve that offers the answer.

But how does the body’s longest cranial nerve, running from brain to large intestine, encodes sensory information from the visceral organs? For his work investigating and mapping this internal information highway, Qiancheng Zhao is the 2024 grand prize winner of the Science & PINS Prize for Neuromodulation.

Interoception—the body’s ability to sense its internal state in a timely and precise manner—facilitated by the vagus plays a key role in respiratory, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, endocrine and immune ...

Current Andean glacier loss is unprecedented in the Holocene

2024-08-01

Andean tropical glaciers are experiencing unprecedented retreat, according to a new study that reveals their current sizes are the smallest in over 11,700 years. “Our finding … identifies this region as a hot spot in our understanding of the changing state of the cryosphere,” say the authors. Glaciers act as important indicators of climate change, with their global retreat accelerating over recent decades. Examining this retreat in the context of the previous 11,700 years of the Holocene interglacial highlights the impact of modern global warming. Although many glaciers worldwide are smaller today compared to ...

New fossil resembling a bristly durian fruit reveals insights into the origin of molluscan skeletons

2024-08-01

The early evolution of mollusks has been hard to pin down, but now a newly discovered fossil – of a shell-less, soft-bodied, spiny mollusk from the early Cambrian – provides crucial insights, researchers report. The findings suggest that this fossil, of a creature called Shishania aculeata, is a stem mollusk – representative of an intermediate between early members of the superphylum lophotrochozoans and more derived mollusks. Mollusks are one of the most diverse groups of animals, encompassing various well-known forms such as clams, ...

CLEAR: a new approach to 3D printing materials with highly entangled polymer networks

2024-08-01

Researchers have developed a novel approach to three-dimensional (3D) printing they call “CLEAR,” which significantly improves the strength and durability of materials by using a combination of light and dark chemical reactions to create densely entangled polymer chains. The authors used their approach to print structures with special features, such as the ability to adhere to wet tissues. Incorporation of polymer chain entanglements as reinforcements within 3D printed materials can significantly enhance their mechanical properties. However, traditional vat photopolymerization-based 3D printing techniques, such as digital ...

Genetic insights into how prickles develop across different plants, despite evolutionary separation

2024-08-01

The evolutionary gain and loss of plant prickles – sharp pointed epidermal outgrowths – are controlled by a shared genetic program involving cytokinin biosynthesis, researchers report. The study sheds light on the genetic basis of the emergence of similar traits in distantly related organisms and reveals genomic targets for prickle removal for crop improvement. The genetic basis of trait convergence is a central question in evolutionary biology, and the extent to which it is driven by ...

Climate anomalies may play a major role in driving cholera pandemics

2024-08-01

New research suggests that an El Niño event may have aided the establishment and spread of a novel cholera strain during an early 20th-century pandemic, supporting the idea that climate anomalies could create opportunities for the emergence of new cholera strains. Xavier Rodo of Instituto de Salud Global de Barcelona, Spain, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Since 1961, more than 1 million people worldwide have died in an ongoing cholera pandemic, the seventh cholera ...

Study shows link between asymmetric polar ice sheet evolution and global climate

2024-08-01

Recent joint research led by Professor AN Zhisheng from the Institute of Earth Environment of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has revealed the pivotal role of the growth of the Antarctic ice sheet and associated Southern Hemisphere sea ice expansion in triggering the mid-Pleistocene climate transition (MPT). It has also shown how asymmetric polar ice sheet evolution affects global climate.

The MPT refers to a shift in Earth’s climate system between about ~1.25–0.7 million years ago, marking a shift to more pronounced and regular ...

When it comes to DNA replication, humans and baker’s yeast are more alike than different

2024-08-01

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (Aug. 1, 2024) — Humans and baker’s yeast have more in common than meets the eye, including an important mechanism that helps ensure DNA is copied correctly, reports a pair of studies published in the journals Science and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

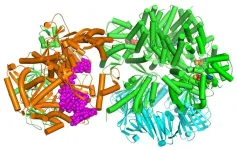

The findings visualize for the first time a molecular complex — called CTF18-RFC in humans and Ctf18-RFC in yeast — that loads a “clamp” onto DNA to keep parts of the replication machinery from falling off the DNA strand.

It is the latest discovery from longtime collaborators Huilin Li, Ph.D., of Van Andel Institute, ...

Aging-related genomic culprit found in Alzheimer’s disease

2024-08-01

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a way to capture the effects of aging in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. They have devised a method to study aged neurons in the lab without a brain biopsy, an advancement that could contribute to a better understanding of the disease and new treatment strategies.

The scientists transformed skin cells taken from patients with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease into brain cells called neurons. Late-onset Alzheimer’s ...

Andean glaciers have retreated to lowest levels in 11,700 years, news study finds

2024-08-01

Chestnut Hill, Mass (8/1/2024) – Rocks recently exposed to the sky after being covered with prehistoric ice show that tropical glaciers have shrunk to their smallest size in more than 11,700 years, revealing the tropics have already warmed past limits last seen earlier in the Holocene age, researchers from Boston College report today in the journal Science.

Scientists have predicted glaciers would melt, or retreat, as temperatures warm in the tropics – those regions bordering the Earth’s ...