(Press-News.org) A new pathway that is used by cancer cells to infiltrate the brain has been discovered by a team of Canadian and American research groups led by the Singh Lab at McMaster University. The research also reveals a new therapy that shows promise in blocking and killing these tumors.

The research, published in Nature Medicine on Aug. 2, 2024, offers new hope and potential treatments for glioblastoma, the most aggressive form of brain cancer. With existing treatments like surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, the tumors often return, and

patient survival is limited to only a few months. With this new treatment, the returning cancer cells were destroyed at least 50 per cent of the time in two of the three diseases tested in preclinical animal models.

To discover the pathway cancer cells use to infiltrate the brain, researchers used large-scale gene editing technology to compare gene dependencies in glioblastoma when it was initially diagnosed and after it returned following standard treatments. By doing this, researchers discovered a new pathway used for axonal guidance – a signalling axis that helps establish normal brain architecture – that can become overrun by cancer cells.

“In glioblastoma, we believe that the tumor hijacks this signalling pathway and uses it to invade and infiltrate the brain,” says co-senior author Sheila Singh, professor with McMaster’s Department of Surgery and director of the Centre for Discovery in Cancer Research. The research was also co-led by Jason Moffat, head of the Genetics and Genome Biology program at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids).

“If we can block this pathway, the hope is that we can block the invasive spread of glioblastoma and kill tumor cells that cannot be removed surgically,” says Singh.

Promising new therapeutic

To stop the invasion of cancer cells, researchers targeted the hijacked signalling pathway using different strategies including a drug developed in John Lazo's group at the University of Virginia, and also by developing a new therapy with help from Kevin Henry and Martin Rossotti at the National Research Council Canada using CAR T cells to target the pathway in the brain. They honed in on a protein called Roundabout Guidance Receptor 1 (ROBO1) that helps guide certain cells, similar to a GPS.

“We created a type of cell therapy where cells are taken from a patient, edited and then put back in with a new function. In this case, the CAR T cells were genetically edited to have the knowledge and ability to go and find ROBO1 on tumor cells in animal models,” says lead author Chirayu Chokshi, a former PhD student who worked alongside Singh at McMaster University.

Singh and Chokshi say the treatment can also apply to other invasive brain cancers. In the study, researchers examined models for three different types of cancer including adult glioblastoma, adult lung-to-brain metastasis, and pediatric medulloblastoma. In all three models, treatment led to a doubling of survival time. In two of the three diseases, it led to tumor eradication in at least 50 per cent of the mice.

“In this study, we present a new CAR T therapy that is showing very promising preclinical results in multiple malignant brain cancer models, including recurrent glioblastoma. We believe our new CAR T therapy is poised for further development and clinical trials,” Singh says.

Work on the study was performed with samples derived from patients treated by neurosurgeons with Hamilton Health Sciences. Proteomics discovery which helped to elucidate the new glioblastoma targets was done in collaboration with Thomas Kilinger at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and University of Toronto. The research was made possible through collaborations the National Research Council Canada, University of Virginia, University of Pittsburgh and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

The study received funding from Brain Cancer Canada, the Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Institutes of Health Mitacs and the Terry Fox Research Institute.

To arrange interviews:

Contact Singh directly at ssingh@mcmaster.ca. Please also include vanoorl@mcmaster.ca on your email to Singh to assist with scheduling.

Contact Chokshi directly at cchokshi08@gmail.com.

For any other assistance or to obtain a copy of the embargoed study, please contact Adam Ward, media relations officer with McMaster University’s Faculty of Health Sciences, at warda17@mcmaster.ca.

END

Researchers develop promising therapy treatment that can kill glioblastoma cells in newly discovered brain pathway

2024-08-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

York researchers make breakthrough in bid to develop vaccines and drugs for neglected tropical disease

2024-08-02

Scientists have developed a new, safe and effective way to infect volunteers with the parasite that causes leishmaniasis and measure the body’s immune response, bringing a vaccine for the neglected tropical disease a step closer.

The breakthrough, by a team from the University of York and Hull York Medical School, is described in the journal Nature Medicine and lays the foundations for vaccine development and for testing new preventative measures.

Controlled human infection studies, where volunteers are exposed to small amounts of ...

Combined effects of plastic pollution and seawater flooding amplify threats to coastal plant species

2024-08-02

Two of the planet’s more pressing environmental stressors have the potential to alter the growth and reproductive output of plants found right along the world’s coastlines, a new study suggests.

The research, published in the journal Environmental Pollution, is one of the first to examine the combined effects of seawater flooding and microplastic pollution on coastal plants.

It showed that both stressors had some effects on the species tested, with microplastics impacting the plants’ reproduction while flooding caused greater tissue death.

However, being exposed to both microplastics ...

Sea level changes shaped early life on Earth, fossil study reveals

2024-08-02

A newly developed timeline of early animal fossils reveals a link between sea levels, changes in marine oxygen, and the appearance of the earliest ancestors of present-day animals.

The study reveals clues into the forces that drove the evolution of the earliest organisms, from which all major animal groups descended.

A team from the University of Edinburgh studied a compilation of rocks and fossils from the so-called Ediacaran-Cambrian interval – a slice of time 580–510 million years ago. This period witnessed an explosion of biodiversity according to fossil records, the causes of which have ...

'Screaming Woman' mummy may have died in agony 3,500 years ago

2024-08-02

In 1935, the Metropolitan Museum of New York led an archaeological expedition to Egypt. In Deir Elbahari near Luxor, the site of ancient Thebes, they excavated the tomb of Senmut, the architect and overseer of royal works – and reputedly, lover – of the famed queen Hatschepsut (1479-1458 BCE). Beneath Senmut's tomb, they found a separate burial chamber for his mother Hat-Nufer and other, unidentified relatives.

Here, they made an uncanny discovery: a wooden coffin holding the mummy of an elderly woman, wearing a black wig and two scarab rings in silver and gold. But what struck the archaeologists was the ...

Healthy AI: Sustainable artificial intelligence for healthcare

2024-08-02

Similar to other sectors around the world, the light speed development of artificial intelligence (AI) has made its way into healthcare, particularly the radiology field. As such, AI-based diagnostic systems are flourishing, with hospitals quickly adopting the technology to assist radiologists. In contrast, there are concerns about the environmental impact of increasingly complex AI models and the need for more sustainable AI solutions.

Therefore, Associate Professor Daiju Ueda of Osaka Metropolitan University’s ...

First full 2-D spectral image of aurora borealis from a hyperspectral camera

2024-08-02

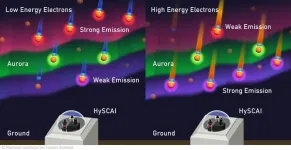

Auroras are natural luminous phenomena caused by the interaction of electrons falling from the sky and the upper atmosphere. Most of the observed light consists of emission lines of neutral or ionized nitrogen and oxygen atoms and molecular emission bands, and the color is determined by the transition energy levels, molecular vibrations and rotations. There is a variety of characteristic colors of auroras, such as green and red, but there are multiple theories about the emission process by which they appear in different types of auroras, and to understand the colors of auroras, the light must be broken down. ...

Turkey vultures fly faster to defy thin air

2024-08-02

Mountain hikes are invigorating. Crisp air and clear views can refresh the soul, but thin air presents an additional challenge for high-altitude birds. ‘All else being equal, bird wings produce less lift in low density air’, says Jonathan Rader from the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, USA, making it more difficult to remain aloft. Yet this doesn’t seem to put them off. Bar-headed geese, cranes and bar-tailed godwits have recorded altitude records of 6000 m and more. So how do they manage to take to the air when thin air offers ...

Texas A&M professor named to Committee on Rural Health by U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services

2024-08-01

Dr. Alva O. Ferdinand, head of the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Texas A&M University School of Public Health, has been named to the Health Resources and Services Administration’s National Advisory Committee on Rural Health by U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra. She will serve a four-year term on the committee, which is comprised of nationally recognized rural health experts tasked with providing recommendations on rural health issues.

Since 2019, Ferdinand has served as director of the Southwest Rural Health Research Center, whose research has impacted federal policies nationwide for more than two decades. ...

Drug developed for pancreatic cancer shows promise against most aggressive form of medulloblastoma

2024-08-01

A drug that was developed to treat pancreatic cancer has now been shown to increase symptom-free survival in preclinical medulloblastoma models – all without showing signs of toxicity.

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumor in children. Survival rates vary according to which one of the four subtypes a patient has, but the worst survival rates, historically at about 40%, are for Group 3, which this research focused on.

Jezabel Rodriguez Blanco, Ph.D., an assistant professor who holds dual appointments at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center and the Darby Children’s ...

Retreat of tropical glaciers foreshadows changing climate's effect on the global ice

2024-08-01

MADISON — As they are in many places around the globe, glaciers perched high in the Andes Mountains are shrinking. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and their collaborators have uncovered evidence that the high-altitude tropical ice fields are likely smaller than they've been at any time since the last ice age ended 11,700 years ago.

That would make the tropical Andes the first region in the world known to pass that threshold as a result of the steadily warming global climate. It also makes them possible harbingers of what's to come for glaciers globally.

"We think these are the canary ...