Turkey vultures fly faster to defy thin air

How large turkey vultures remain aloft in thin air

2024-08-02

(Press-News.org) Mountain hikes are invigorating. Crisp air and clear views can refresh the soul, but thin air presents an additional challenge for high-altitude birds. ‘All else being equal, bird wings produce less lift in low density air’, says Jonathan Rader from the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, USA, making it more difficult to remain aloft. Yet this doesn’t seem to put them off. Bar-headed geese, cranes and bar-tailed godwits have recorded altitude records of 6000 m and more. So how do they manage to take to the air when thin air offers little lift? One possibility was that birds at high altitude simply fly faster, to compensate for the lower air density, but it wasn’t clear whether birds that naturally inhabit a wide range of altitudes, from sea level to the loftiest summits, might fine-tune their flight speed to compensate for thin air. ‘Turkey vultures are common through North America and inhabit an elevation range of more than 3000 m’, says Rader, so he and Ty Hedrick (UNC-Chapel Hill) decided to find out whether turkey vultures (Cathartes aura) residing at different elevations fly at different speeds depending on their altitude. They publish their discovery in Journal of Experimental Biology that turkey vultures fly faster at altitude to compensate for the lack of lift caused by flying in thin air.

First the duo needed to select locations over several thousand meters’ altitude, so they started filming the vultures flying at the local Orange County refuse site (80 m above sea level); ‘Vultures on a landfill… who would have guessed?’, chuckles Rader. Then they relocated to Rader’s home state of Wyoming, visiting Alcova (1600 m) before ending up at the University of Wyoming campus in Laramie (2200 m). At each location, the duo set up three synchronized cameras with a clear view to a tree that was home to a roosting colony of turkey vultures, ready to film the vultures’ flights in 3D as they flew home at the end of the day. ‘Wyoming is a famously windy place and prone to afternoon thunderstorms’, Rader explains, recalling being chased off the roof of the University of Wyoming Biological Sciences Building by storms and the wind blurring movies of the flying birds as it rattled the cameras.

Back in North Carolina, Rader reconstructed 2458 bird flights from the movies, calculating their flight speed before converting to airspeed, which ranged from 8.7 to 13.24m/s. He also calculated the air density at each location, based on local air pressure readings, recording a 27% change from 0.89kg/m3 at Laramie to 1.227 kg/m3 at Chapel Hill. After plotting the air densities at the time of flight against the birds’ airspeeds on a graph, Rader and Hedrick could see that the birds flying at 2200m in Laramie were generally flying ~1m/s faster than the birds in Chapel Hill. Turkey vultures fly faster at higher altitudes to remain aloft. But how do they achieve these higher airspeeds?

Rader returned to the flight movies, looking for the tell-tale up-and-down motion that would indicate when they were flapping. However, when he compared how much each bird was flapping with the different air densities, the high-altitude vultures were flapping no more than the birds nearer to sea level, so they weren’t changing their wingbeats to counteract the effects of low air density. Instead, it is likely that the 2200 m high birds were flying faster simply because there is less drag in thin air to slow them down, allowing the Laramie vultures to fly faster than the Chapel Hill birds to compensate for generating less lift in lower air density.

IF REPORTING THIS STORY, PLEASE MENTION JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY AS THE SOURCE AND, IF REPORTING ONLINE, PLEASE CARRY A LINK TO: https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article-lookup/doi/10.1242/jeb.246828

REFERENCE: Rader, J. A. and Hedrick, T. L. (2024). Turkey vultures tune their airspeed to changing air density. J. Exp. Biol. 227, jeb246828. doi:10.1242/jeb.246828

DOI: 10.1242/jeb.246828

Registered journalists can obtain a copy of the article under embargo from http://pr.biologists.com. Unregistered journalists can register at http://pr.biologists.com to access the embargoed content. The embargoed article can also be obtained from Kathryn Knight (kathryn.knight@biologists.com)

This article is posted on this site to give advance access to other authorised media who may wish to report on this story. Full attribution is required and if reporting online a link to https://journals.biologists.com/jeb is also required. The story posted here is COPYRIGHTED. Advance permission is required before any and every reproduction of each article in full from permissions@biologists.com.

THIS ARTICLE IS EMBARGOED UNTIL THURSDAY, 1 AUGUST 2024, 18:00 HRS EDT (23:00 HRS BST)

info for journalists ONLY: The embargoed text of the article and embargoed multimedia are available to registered journalists at http://pr.biologists.com. Unregistered journalists must register at http://pr.biologists.com to access the embargoed content. For other enquiries, please contact Kathryn Knight at kathryn.knight@biologists.com

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-08-01

Dr. Alva O. Ferdinand, head of the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Texas A&M University School of Public Health, has been named to the Health Resources and Services Administration’s National Advisory Committee on Rural Health by U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra. She will serve a four-year term on the committee, which is comprised of nationally recognized rural health experts tasked with providing recommendations on rural health issues.

Since 2019, Ferdinand has served as director of the Southwest Rural Health Research Center, whose research has impacted federal policies nationwide for more than two decades. ...

2024-08-01

A drug that was developed to treat pancreatic cancer has now been shown to increase symptom-free survival in preclinical medulloblastoma models – all without showing signs of toxicity.

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumor in children. Survival rates vary according to which one of the four subtypes a patient has, but the worst survival rates, historically at about 40%, are for Group 3, which this research focused on.

Jezabel Rodriguez Blanco, Ph.D., an assistant professor who holds dual appointments at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center and the Darby Children’s ...

2024-08-01

MADISON — As they are in many places around the globe, glaciers perched high in the Andes Mountains are shrinking. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and their collaborators have uncovered evidence that the high-altitude tropical ice fields are likely smaller than they've been at any time since the last ice age ended 11,700 years ago.

That would make the tropical Andes the first region in the world known to pass that threshold as a result of the steadily warming global climate. It also makes them possible harbingers of what's to come for glaciers globally.

"We think these are the canary ...

2024-08-01

Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital have created a panel that is able to provide a diagnosis for >90% of pediatric cancer patients by sequencing 0.15% of the human genome. The panel is a cost-effective way to test and classify childhood malignancies and to help guide patient treatment. The panel’s performance and validation were published this week in Clinical Cancer Research.

Finding the mutations in a child’s cancer with powerful sequencing technology can lead to better outcomes. Physicians use that knowledge to tailor targeted treatments to the specific cancer-causing mutations affecting each patient. However, current ...

2024-08-01

Prior authorization—the process by which a health insurance company denies or approves coverage for a health care service before the service is performed—became standard practice beginning with Medicare and Medicaid legislation in the 1960s.

Although research has uncovered disparities in prior coverage for cancer patients based on race, little has been known to date on the role of prior authorization in increasing or decreasing these disparities.

To learn more about the issue, Benjamin Ukert, PhD, an assistant professor of health policy and management in the Texas A&M ...

2024-08-01

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Snacks provide, on average, about one-fourth of most people’s daily calories. With nearly one in three adults in the United States overweight and more than two in five with obesity, according to the National Institutes of Health, researchers in the Penn State Sensory Evaluation Center are investigating how Americans can snack smarter.

The latest study conducted in the center, housed in the College of Agricultural Sciences, investigated how eating behavior changes when consumers are served a dip with a salty snack. The findings, available online now and to be published in the November issue ...

2024-08-01

Seven entrepreneurs comprise the next cohort of Innovation Crossroads, a Department of Energy Lab-Embedded Entrepreneurship Program node based at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The program provides energy-related startup founders from across the nation with access to ORNL’s unique scientific resources and capabilities, as well as connect them with experts, mentors and networks to accelerate their efforts to take their world-changing ideas to the marketplace.

“Supporting the next generation of entrepreneurs is part of ORNL’s ...

2024-08-01

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Aug. 1, 2024

Media Contact:

Monica McDonald

(404) 365-2162

mmcdonald@rheumatology.org

American College of Rheumatology Opens Press Registration for ACR Convergence 2024

ATLANTA – Complimentary press registration is now open for journalists to cover research presented at ACR Convergence 2024, taking place Nov. 14-19 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. A listing of sessions for the meeting can be found in the online program.

Approved ...

2024-08-01

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 19:00 BST / 14:00 ET THURSDAY 1 AUGUST 2024

Images available via link in the notes section

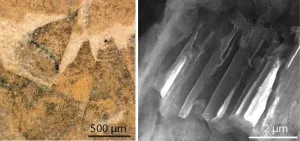

Exceptional fossils with preserved soft parts reveal that the earliest molluscs were flat, armoured slugs without shells.

The new species, Shishania aculeata was covered with hollow, organic, cone-shaped spines.

The fossils preserve exceptionally rare detailed features which reveal that these spines were produced using a sophisticated secretion system that is shared with annelids (earthworms and relatives).

A team of researchers including scientists from the University of Oxford have made an astonishing discovery of ...

2024-08-01

When the question is “how are you feeling on the inside?,” it’s our vagus nerve that offers the answer.

But how does the body’s longest cranial nerve, running from brain to large intestine, encodes sensory information from the visceral organs? For his work investigating and mapping this internal information highway, Qiancheng Zhao is the 2024 grand prize winner of the Science & PINS Prize for Neuromodulation.

Interoception—the body’s ability to sense its internal state in a timely and precise manner—facilitated by the vagus plays a key role in respiratory, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, endocrine and immune ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Turkey vultures fly faster to defy thin air

How large turkey vultures remain aloft in thin air