(Press-News.org) August 8, 2024—(BRONX NY)—A discovery by a three-member Albert Einstein College of Medicine research team may boost the effectiveness of stem-cell transplants, commonly used for patients with cancer, blood disorders, or autoimmune diseases caused by defective stem cells, which produce all the body’s different blood cells. The findings, made in mice, were published today in the journal Science.

“Our research has the potential to improve the success of stem-cell transplants and expand their use,” explained Ulrich Steidl, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chair of cell biology, interim director of the Ruth L. and David S. Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell Research and Regenerative Medicine, and the Edward P. Evans Endowed Professor for Myelodysplastic Syndromes at Einstein, and deputy director of the National Cancer Institute-designated Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center (MECCC).

Dr. Steidl, Einstein’s Britta Will, Ph.D., and Xin Gao, Ph.D., a former Einstein postdoctoral fellow, now at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, are co-corresponding authors on the paper.

Mobilizing Stem Cells

Stem-cell transplants treat diseases in which an individual’s hematopoietic (blood-forming) stem cells (HSCs) have become cancerous (as in in leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes) or too few in number (as in bone marrow failure and severe autoimmune disorders). The therapy involves infusing healthy HSCs obtained from donors into patients. To harvest those HSCs, donors are given a drug that causes HSCs to mobilize, or escape, from their normal homes in the bone marrow and enter the blood, where HSCs can be separated from other blood cells and then transplanted. However, drugs used to mobilize HSCs often don’t liberate enough of them for the transplant to be effective.

“It’s normal for a tiny fraction of HSCs to exit the bone marrow and enter the blood stream, but what controls this mobilization isn’t well understood,” said Dr. Will, associate professor of oncology and of medicine, and the Diane and Arthur B. Belfer Faculty Scholar in Cancer Research at Einstein, and the co-leader of the Stem Cell and Cancer Biology research program at MECCC. “Our research represents a fundamental advance in our understanding, and points to a new way to improve HSC mobilization for clinical use.”

Tracking Trogocytosis

The researchers suspected that variations in proteins on the surface of HSCs might influence their propensity to exit the bone marrow. In studies involving HSCs isolated from mice, they observed that a large subset of HSCs display surface proteins normally associated with macrophages, a type of immune cell. Moreover, HSCs with these surface proteins largely stayed in the bone marrow, while those without the markers readily exited the marrow when drugs for boosting HSCs mobilization were given.

After mixing HSCs with macrophages, the researchers discovered that some HSCs engaged in trogocytosis, a mechanism whereby one cell type extracts membrane fractions of another cell type and incorporates them into their own membranes. Those HSCs expressing high levels of the protein c-Kit on their surface were able to carry out trogocytosis, causing their membranes to be augmented with macrophage proteins—and making them far more likely than other HSCs to stay in the bone marrow. The findings suggest that impairing c-Kit would prevent trogocytosis, leading to more HSCs being mobilized and made available for transplantation.

“Trogocytosis plays a role in regulating immune responses and other cellular systems, but this is the first time anyone has seen stem cells engage in the process. We are still seeking the exact mechanism for how HSCs regulate trogocytosis,” said Dr. Goa, assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

The researchers intend to continue their investigation into this process: “Our ongoing efforts will look for other functions of trogocytosis in HSCs, including potential roles in blood regeneration, eliminating defective stem cells and in hematologic malignancies,” added Dr. Will.

The study originated in the laboratory of the late Paul S. Frenette, M.D., a pioneer in hematopoietic stem cell research and founding director of the Ruth L. and David S. Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Research at Einstein. Other key contributors include Randall S. Carpenter, Ph.D., and Philip E. Boulais, Ph.D., both postdoctoral scientists at Einstein.

The Science paper is titled, “Regulation of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by c-Kit-associated trogocytosis.” Additional authors are Huihui Li, Ph.D., and Maria Maryanovich, Ph.D., both at Einstein, Christopher R. Marlein, Ph.D., at Einstein and FUJIFILM Diosynth Biotechnologies, Wilton, England, and Dachuan Zhang, Ph.D., at Einstein and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China, Matthew Smith at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and David J. Chung, M.D., Ph.D., at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (U01DK116312, R01DK056638, R01DK112976, R01HL069438, DK10513, CA230756, R01HL157948 and R35CA253127).

***

About Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Albert Einstein College of Medicine is one of the nation’s premier centers for research, medical education and clinical investigation. During the 2023-24 academic year, Einstein is home to 737 M.D. students, 209 Ph.D. students, 124 students in the combined M.D./Ph.D. program, and approximately 239 postdoctoral research fellows. The College of Medicine has more than 2,000 full-time faculty members located on the main campus and at its clinical affiliates. In 2023, Einstein received more than $192 million in awards from the National Institutes of Health. This includes the funding of major research centers at Einstein in cancer, aging, intellectual development disorders, diabetes, clinical and translational research, liver disease, and AIDS. Other areas where the College of Medicine is concentrating its efforts include developmental brain research, neuroscience, cardiac disease, and initiatives to reduce and eliminate ethnic and racial health disparities. Its partnership with Montefiore, the University Hospital and academic medical center for Einstein, advances clinical and translational research to accelerate the pace at which new discoveries become the treatments and therapies that benefit patients. For more information, please visit einsteinmed.edu, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and view us on YouTube.

END

While seeking to unravel how marine algae create their chemically complex toxins, scientists at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography have discovered the largest protein yet identified in biology. Uncovering the biological machinery the algae evolved to make its intricate toxin also revealed previously unknown strategies for assembling chemicals, which could unlock the development of new medicines and materials.

Researchers found the protein, which they named PKZILLA-1, while studying how a type of algae called Prymnesium parvum makes its toxin, which is responsible for massive fish kills.

“This is the Mount Everest of proteins,” ...

Voids or pores have usually been viewed as fatal flaws that severely degrade a material's mechanical performance and should be eliminated in manufacturing.

However, a research team led by Prof. JIN Haijun from the Institute of Metal Research (IMR) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has proposed that the presence of voids is not always hazardous. Instead, voids can be beneficial if they are added "properly" to the material.

The team demonstrated that a metal with a large number of nanoscale voids shows improved ...

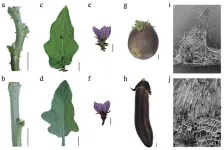

Scientists have discovered the gene responsible for prickles in eggplants, a trait that complicates farming. Using advanced genetic techniques, they identified the Prickly Eggplant (PE) gene on chromosome 6 and pinpointed SmLOG1 as the key factor. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing confirmed that disabling SmLOG1 eliminates prickles, paving the way for prickle-free eggplant varieties. This breakthrough not only sheds light on prickle development but also promises to streamline eggplant cultivation and harvesting, benefiting the agricultural industry.

Eggplants, a staple crop globally, present significant challenges in cultivation and harvesting due to their prickles. These prickles, which serve as ...

People eat either because they are hungry or for pleasure, even in the absence of hunger. While hunger-driven eating is fundamental for survival, pleasure-driven feeding may accelerate the onset of obesity and associated metabolic disorders. A study published in Nature Metabolism reveals neural circuits in the mouse brain that promote hunger-driven feeding and suppress pleasure-driven eating. The findings open new possibilities for developing strategies to combat obesity.

“Ideal feeding habits would balance eating for necessity and for pleasure, minimizing the latter,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Yong Xu, ...

“These findings indicate that renalase-1 is a potential antigen for TCR recognition in melanoma and could be considered as a target for immunotherapy.”

BUFFALO, NY- August 8, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on August 5, 2024, entitled, “Chemical complementarity of tumor resident, T-cell receptor CDR3s and renalase-1 correlates with increased melanoma survival.”

As mentioned in the Abstract of this study, overexpression of the secretory protein renalase-1 negatively impacts the survival of melanoma and pancreatic cancer patients, while inhibition of renalase-1 signaling drives tumor ...

Key Takeaways

-Fusion has the potential to provide abundant clean energy

-One to two-year awards range from $100,000 to $500,000

In a continuing effort to forge and fund public-private partnerships to accelerate fusion research, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) today awarded $4.6 million in 17 awards to U.S. businesses via the Innovation Network for Fusion Energy (INFUSE) program.

The goal of INFUSE is to accelerate fusion energy development in the private sector by reducing impediments to collaboration between business ...

Following the Mediterranean diet versus the traditional Western diet might make you feel like you’re under less stress, according to new research conducted by a team from Binghamton University, State University of New York.

The findings suggest that people can lower their perception of how much stress they can tolerate by following a Mediterranean diet, said Lina Begdache, associate professor of health and wellness studies.

“Stress is recognized to be a precursor to mental distress, and research, including our own, has demonstrated that the Mediterranean diet lowers ...

A recent study investigates the intricate mechanisms of sugar import in developing seeds of Camellia oleifera. By identifying key sugar transporters and analyzing their roles, the research provides significant insights into the molecular regulation of seed development. The findings highlight how these transporters, working alongside sucrose-metabolizing enzymes, facilitate efficient sugar import and partitioning. This study not only advances our understanding of seed development in Camellia oleifera but also suggests potential strategies to enhance seed yield and quality in this important ...

Ann Arbor, August 8, 2024 – Media coverage of shootings by police typically involve urban incidents, giving the impression that the issue is unique to cities. However, national data built from the Gun Violence Archive tells a different story, showing a higher rate of shootings by police in rural and suburban areas than in cities during 2015-2020. A new study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, published by Elsevier, reports on the first nationwide, descriptive analysis of where, how often, and under ...

SAN ANTONIO, Aug. 8, 2024 – A drug effective in treating breast cancer shows new promise in addressing breast cancer with brain metastases or recurrent glioblastoma, as reported by results of a prospective window-of-opportunity trial at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio).

The window trial, in which patients agreed to receive a novel treatment before undergoing surgery, found that the drug Sacituzumab Govitecan was well-tolerated and showed signs of effectiveness for those whose breast cancer had progressed to brain tumors.

About half of all women with ...