(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – Anyone who’s tried to neatly gather a fitted sheet can tell you: folding is hard. Get it wrong with your laundry and the result can be a crumpled, wrinkled mess of fabric, but when folding fails among the approximately 7,000 proteins with an origami-like complexity that regulate essential cellular functions, the result can lead to one of a multitude of serious diseases ranging from emphysema and cystic fibrosis to Alzheimer’s disease. Fortunately, our bodies have a quality-control system that identifies misfolded proteins and marks them either for additional folding work or destruction, but how, exactly, this quality-control process functions is not entirely known. Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have now made a major leap forward in our understanding of how this quality-control system works by discovering the “hot spot” where all the action takes place. The research was published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DNA may be the master blueprint for life, but it is of proteins that we’re built. While many of them are structurally simple, there are approximately 7,000 proteins that must be made in a cell’s secretory pathway and will be either dispersed throughout the cell or secreted to the extracellular space in order to perform their essential functions.

The story begins in the endoplasmic reticulum—the cellular protein factories responsible for correctly building thousands of different proteins—and involves two main players: an enzyme known as UGGT and the partner protein Sep15. Senior authors Daniel Hebert, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at UMass Amherst, and Lila Gierasch, distinguished professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and chemistry at UMass Amherst, along with co-author, Kevin Guay, a graduate student in the molecular cellular biology program at UMass Amherst, had shown in previous research that UGGT acts as a “gatekeeper” by reading carbohydrate tags, called N-glycans, embedded into the protein to determine whether or not the protein is correctly folded.

“But there’s something else at work,” says lead-author Rob Williams, a postdoctoral fellow with a joint appointment in both Hebert’s and Gierasch’s labs. “There’s an exclusive club of proteins called ‘selenoproteins,’ which contain the rare element selenium. Out of approximately 20,000 different proteins in our bodies, only 25 of them are selenoproteins. The UGGT partner Sep15 is a selenoprotein. Sep15 is always associated with UGGT. But until now, no one knew what it was doing there.”

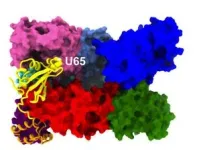

Using an AI model called AlphaFold2, Williams and his co-authors predicted that the protein Sep15 forms a complex helical shape that looks something like a catcher’s mitt, and that this mitt perfectly matches a complementary site on the UGGT enzyme. The specific site where SEP15 and UGGT bind is also where UGGT reads the N-glycan code that tells it whether or not a protein is correctly folded.

“Basically,” says Hebert, “we’ve found the hotspot where all the action is taking place—and Sep15 is the key.”

To test their AlphaFold2-generated prediction, the research team designed an experiment using recombinant DNA re-engineering of UGGT to interrupt its binding to Sep15—and, indeed, the modified UGGT failed to form a complex with Sep15.

So what, exactly, is Sep15 doing? “There are two possibilities, both of which we’re following up on,” says Hebert. “Either Sep15 is giving the misfolded protein a chance at correcting its shape, or it is marking that protein for destruction.”

“The complexity of the proteins we are studying allows higher forms of life to function,” says Gierasch, “but the complexity of those proteins also means that they’re more prone to misfolding errors, and misfolding errors can have catastrophic consequences if the quality control process fails.”

Though there is still a great deal of basic research to be done, the team’s research sets the stage for novel drug therapies that target the Sep15/UGGT interface. “This is an untapped pharmaceutical area,” says Hebert, “and Williams’s research has moved us in the right direction for eventual treatment.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences and facilitated by the availability of instrumentation in the UMass Amherst Institute for Applied Life Sciences.

Contacts: Lila Gierasch, gierasch@biochem.umass.edu

Daniel Hebert, dhebert@biochem.umass.edu

Daegan Miller, drmiller@umass.edu

END

UMass Amherst researchers ID body’s ‘quality control’ regulator for protein folding

New research could pave the way for novel drug therapies targeting the site where misfolds occur

2024-08-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Forest restoration can boost people, nature and climate simultaneously

2024-08-12

Forest restoration can benefit humans, boost biodiversity and help tackle climate change simultaneously, new research suggests.

Restoring forests is often seen in terms of “trade-offs” – meaning it often focuses on a specific goal such as capturing carbon, nurturing nature or supporting human livelihoods.

The new study, by the universities of Exeter and Oxford, found that restoration plans aimed at a single goal tend not to deliver the others.

However, “integrated” plans would deliver over 80% of the benefits in all three areas at once.

It also found that ...

Pre-surgical antibody treatment might prevent heart transplant rejection

2024-08-12

A new study from scientists at Cincinnati Children’s suggests there may be a way to further protect transplanted hearts from rejection by preparing the donor organ and the recipient with an anti-inflammatory antibody treatment before surgery occurs.

The findings, published online in PNAS, focus on blocking an innate immune response that normally occurs in response to microbial infections. The same response has been shown to drive dangerous inflammation in transplanted hearts.

In the new study – in mice -- transplanted hearts functioned for longer periods when the organ recipients ...

Scientists identify genes linked to relapse in the most common form of childhood leukemia

2024-08-12

Scientists from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Seattle Children’s and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) have identified novel genetic variations that influence relapse risk in children with standard risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (SR B-ALL), the most common childhood cancer. The identification of genomic predictors of relapse in SR B-ALL provides a basis for improved diagnosis, precise tailoring of treatment intensity and potentially the development of novel treatment approaches. The study was published today in the Journal of ...

Local solvation is decisive for fluorescence of biosensors

2024-08-12

At Ruhr University, the groups of Professor Martina Havenith and Professor Sebastian Kruss collaborated for the study, which took place as part of the Cluster of Excellence “Ruhr Explores Solvation”, RESOLV for short. The PhD students Sanjana Nalige and Phillip Galonska made significant contributions.

Carbon nanotubes as biosensors

Single-walled carbon nanotubes are powerful building blocks for biosensors, as previous studies revealed. Their surface can be chemically tailored with biopolymers or DNA fragments to interact specifically with a certain target molecule. When such molecules bind, the nanotubes change their emission ...

Parents who use humor have better relationships with their children, study finds

2024-08-12

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — They say that laughter is the best medicine, but it could be a good parenting tool too, according to a new study led by researchers from Penn State.

In a pilot study, the research team found that most people viewed humor as an effective parenting tool and that a parent or caregiver’s use of humor affected the quality of their relationship with their children. Among those whose parents used humor, the majority viewed their relationship with their parents and the way they were ...

HHMI invests $500 million in AI-driven life sciences research

2024-08-12

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute today announced AI@HHMI, a $500 million investment over the next 10 years to support artificial intelligence-driven projects in the life sciences. As the largest private biomedical research organization in the United States, HHMI aims to explore the full promise of AI to accelerate scientific discovery at its Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia, and at the more than 300 HHMI-affiliated labs.

“By bringing human curiosity and artificial intelligence closer together at every phase of experimentation ...

Locked out of banking: Incarceration is associated with decreased bank account ownership

2024-08-12

People who have served time in jail or prison are less likely to have bank accounts after they are released than they were before serving time, which may hinder their long-term financial security, according to new research.

“Locked out of banking: The limits of financial inclusion for formerly incarcerated individuals” was authored by Brielle Bryan, an assistant professor of sociology at Rice University and J. Michael Collins, a professor of public affairs and human ecology and the Fetzer Family Chair in Consumer and Personal Finance at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It ...

Research spotlight: Generative AI “drift” and “nondeterminism” inconsistences are important considerations in healthcare applications

2024-08-12

Samuel (Sandy) Aronson, ALM, MA, executive director of IT and AI Solutions for Mass General Brigham Personalized Medicine and senior director of IT and AI Solutions for the Accelerator for Clinical Transformation, is the corresponding author of a paper published in NEJM AI that looked at whether generative AI could hold promise for improving scientific literature review of variants in clinical genetic testing. Their findings could have a wide impact beyond this use case.

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

We tested whether ...

Comprehensive atlas of normal breast cells offers new tool for understanding breast cancer origin

2024-08-12

INDIANAPOLIS — Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center have completed the most extensive mapping of healthy breast cells to date. These findings offer an important tool for researchers at IU and beyond to understand how breast cancer develops and the differences in breast tissue among genetic ancestries.

Published this month in Nature Medicine, researchers developed a comprehensive atlas of breast tissue cells – including details ...

Huang studying electric distribution system protection – Modeling and testing with real-time digital simulator

2024-08-12

Liling Huang, Associate Professor, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Dominion Energy Faculty Fellow, received funding for: “Electric Distribution System Protection - Modeling and Testing with Real-Time Digital Simulator.”

Huang will address the complexities of the electric distribution system introduced by Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) through Real-Time Digital Simulator (RTDS) modeling and Hardware-in-the Loop (HIL) simulation to enhance protection system ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

[Press-News.org] UMass Amherst researchers ID body’s ‘quality control’ regulator for protein foldingNew research could pave the way for novel drug therapies targeting the site where misfolds occur