(Press-News.org) The ability to turn experiences into memories allows us to learn from the past and use what we learned as a model to respond appropriately to new situations. For this reason, as the world around us changes, this memory model cannot simply be a fixed archive of the good old days. Rather, it must be dynamic, changing over time and adapting to new circumstances to better help us predict the future and select the best course of action. How the brain could regulate a memory’s dynamics was a mystery – until multiple memory copies were discovered.

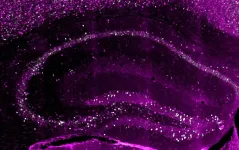

Professor Flavio Donato's research group at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, uses mouse models to investigate how memories are stored in the brain and how they change throughout life. His team has now revealed that in the hippocampus, a brain region responsible for learning from experience, a single event is stored in parallel memory copies among at least three different groups of neurons, which emerge at different stages during embryonic development.

Memory copies come and go, and change with time

First to arrive during development, the early-born neurons are responsible for the long-term persistence of a memory. In fact, even though their memory copy is initially too weak for the brain to access, it becomes stronger and stronger as time passes. Also in humans, the brain might have access to such memory only some time after its encoding.

In contrast, the memory copy of the same event created by the late-born neurons is very strong at the beginning but fades over time, so that if one waits long enough, such a copy becomes inaccessible to the brain. In the middle ground, among neurons emerging in between the two extremes during development, a more stable copy could be observed.

Surprisingly, which copy is used might also be linked to how easy it is to change a memory – or to use it to create a new one. The memories stored for a short time after acquisition by the late-born neurons can be modified and rewritten. This means that remembering a situation shortly after it has happened primes the late-born neurons to become active and integrate present information within the original memory. On the contrary, remembering the same event after a long time primes the early-born neurons to be re-activated to retrieve their copy, but the associated memory can no longer easily be modified. “How dynamically memories are stored in the brain is proof of the brain’s plasticity, which underpins its enormous memory capacity”, says first author Vilde Kveim.

Flexible memories enable appropriate behavior

Flavio Donato’s research team has thus demonstrated that the activation of specific memory copies and their timing could have significant consequences on how we remember, change, and use our memories. “The challenge the brain faces with memory is quite impressive. On one hand, it must remember what happened in the past, to help us make sense of the world we live in. On the other, it needs to adapt to changes happening all around us, and so must our memories, to help us make appropriate choices for our future”, says Flavio Donato.

Persistence through dynamics is a delicate act to balance, one for which we might now have an entry point to fully understand. The researchers hope that one day, understanding what drives memories to be encoded and modified in the brain might help to soften those memories that are pathologically intrusive in our daily life, or bring back some that we thought lost forever.

The ability to turn experiences into memories allows us to learn from the past and use what we learned as a model to respond appropriately to new situations. For this reason, as the world around us changes, this memory model cannot simply be a fixed archive of the good old days. Rather, it must be dynamic, changing over time and adapting to new circumstances to better help us predict the future and select the best course of action. How the brain could regulate a memory’s dynamics was a mystery – until multiple memory copies were discovered.

END

The brain creates three copies for a single memory

2024-08-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Breakthrough addresses sex-related weight gain and disease

2024-08-15

ITHACA, N.Y. -- A decline in estrogen during menopause causes changes in body fat distribution and associated cardiovascular and metabolic disease, but a new study identifies potential therapies that might one day reverse these unhealthy shifts.

The study, “Cxcr4 Regulates a Pool of Adipocyte Progenitors and Contributes to Adiposity in a Sex-Dependent Manner,” was published Aug. 5 in Nature Communications.

The researchers discovered that a receptor called Cxcr4, when blocked in mice, reduced the tendency of fat stem cells to develop into white fat, also called white adipose tissue. This treatment could potentially be combined with low doses of estrogen therapy to cut ...

As human activities expand in Antarctica, scientists identify crucial conservation sites

2024-08-15

A team of scientists led by the University of Colorado Boulder has identified 30 new areas critical for conserving biodiversity in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica. In a study published Aug. 15 in the journal Conservation Biology, the researchers warn that without greater protection to limit human activities in these areas, native wildlife could face significant population declines.

“Many animals are only found in the Southern Ocean, and they all play an important role in its ecosystem,” said Cassandra Brooks, the paper’s senior author and associate professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and a fellow of the ...

Solutions to Nigeria’s newborn mortality rate might lie in existing innovations, finds review

2024-08-15

The review, led by Imperial College London’s Professor Hippolite Amadi, argues that Nigeria’s own discoveries and technological advancements of the past three decades have been “abandoned” by policymakers.

The authors argue that too many Nigerian newborns, clinically defined as infants in the first 28 days of life, die of causes that could have been prevented had policymakers adopted recent in-country scientific breakthroughs.

Led by Professor Amadi of Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, who received the Nigeria Prize ...

Study highlights sex differences in notified infectious disease cases across Europe

2024-08-15

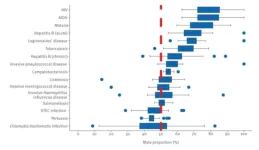

A study published in Eurosurveillance analysing 5.5 million cases of infectious diseases in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) over 10 years has found important differences in the relative proportion of notified male versus female cases for several diseases. The proportion of males ranged on average from 40-45% for pertussis and Shiga toxin-producing Escherischia coli (STEC) infections to 75-80% for HIV/AIDS.

“Although this study was not able to fully explain the differences observed across countries and diseases, it offers some interesting leads,” said Julien Beauté, principal expert in general surveillance at the European ...

Nanobody inhibits metastasis of breast tumor cells to lung in mice

2024-08-15

“In the present study we describe the development of an inhibitory nanobody directed against an extracellular epitope present in the native V-ATPase c subunit.”

BUFFALO, NY- August 15, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on August 14, 2024, entitled, “A nanobody against the V-ATPase c subunit inhibits metastasis of 4T1-12B breast tumor cells to lung in mice.”

The vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) is an ATP-dependent proton pump that functions to control the pH of intracellular compartments ...

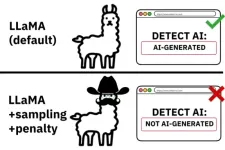

Detecting machine-generated text: An arms race with the advancements of large language models

2024-08-15

Machine-generated text has been fooling humans for the last four years. Since the release of GPT-2 in 2019, large language model (LLM) tools have gotten progressively better at crafting stories, news articles, student essays and more, to the point that humans are often unable to recognize when they are reading text produced by an algorithm. While these LLMs are being used to save time and even boost creativity in ideating and writing, their power can lead to misuse and harmful outcomes, which are already ...

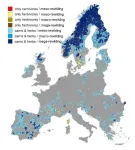

Nearly 25% of European landscape could be rewilded

2024-08-15

Europe's abandoned farmlands could find new life through rewilding, a movement to restore ravaged landscapes to their wilderness before human intervention. A quarter of the European continent, 117 million hectares, is primed with rewilding opportunities, researchers report August 15 in the Cell Press journal Current Biology. They provide a roadmap for countries to meet the 2030 European Biodiversity Strategy's goals to protect 30% of land, with 10% of those areas strictly under conservation.

The team ...

Emergency departments could help reduce youth suicide risk

2024-08-15

A study of over 15,000 youth with self-inflicted injury treated in Emergency Departments (EDs) found that around 25 percent were seen in the ED within 90 days before or 90 days after injury, pointing to an opportunity for ED-based interventions, such as suicide risk screening, safety planning, and linkage to services. Nearly half of ED visits after the self-inflicted injury encounter were for mental health issues.

“Self-inflicted injury is an important predictor of suicide risk,” said Samaa Kemal, MD, MPH, emergency medicine physician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie ...

Uterus transplant in women with absolute uterine-factor infertility

2024-08-15

About The Study: Uterus transplant was technically feasible and was associated with a high live birth rate following successful graft survival. Adverse events were common, with medical and surgical risks affecting recipients as well as donors. Congenital abnormalities and developmental delays have not occurred to date in the live-born children.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Liza Johannesson, MD, PhD, email Liza.Johannesson@bswhealth.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.11679)

Editor’s ...

Adverse childhood experiences and adult household firearm ownership

2024-08-15

About The Study: Consistent with prior research on adverse childhood experience (ACE; defined as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction before age 18) exposure and presence of a firearm in the household during childhood, this study found that cumulative ACE exposure was associated with higher odds of household firearm ownership in adulthood. The relationship may be due to a heightened sense of vulnerability to physical violence and greater perceived threats to personal safety associated with a traumatic childhood, which lead individuals to seek self-protection.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Alexander Testa, PhD, email alexander.testa@uth.tmc.edu.

To ...