(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) — While a mosquito bite is often no more than a temporary bother, in many parts of the world it can be scary. One mosquito species, Aedes aegypti, spreads the viruses that cause over 100,000,000 cases of dengue, yellow fever, Zika and other diseases every year. Another, Anopheles gambiae, spreads the parasite that causes malaria. The World Health Organization estimates that malaria alone causes more than 400,000 deaths every year. Indeed, their capacity to transmit disease has earned mosquitoes the title of deadliest animal.

Male mosquitoes are harmless, but females need blood for egg development. It’s no surprise that there’s over 100 years of rigorous research on how they find their hosts. Over that time, scientists have discovered there is no one single cue that these insects rely on. Instead, they integrate information from many different senses across various distances.

A team led by researchers at UC Santa Barbara has added another sense to the mosquito’s documented repertoire: infrared detection. Infrared radiation from a source roughly the temperature of human skin doubled the insects’ overall host-seeking behavior when combined with CO2 and human odor. The mosquitoes overwhelmingly navigated toward this infrared source while host seeking. The researchers also discovered where this infrared detector is located and how it works on a morphological and biochemical level. The results are detailed in the journal Nature.

“The mosquito we study, Aedes aegypti, is exceptionally skilled at finding human hosts,” said co-lead author Nicolas DeBeaubien, a former graduate student and postdoctoral researcher at UCSB in Professor Craig Montell’s laboratory. “This work sheds new light on how they achieve this.”

Guided by thermal infrared

It is well established that mosquitoes like Aedes aegypti use multiple cues to home in on hosts from a distance. “These include CO2 from our exhaled breath, odors, vision, [convection] heat from our skin, and humidity from our bodies,” explained co-lead author Avinash Chandel, a current postdoc at UCSB in Montell’s group. “However, each of these cues have limitations.” The insects have poor vision, and a strong wind or rapid movement of the human host can throw off their tracking of the chemical senses. So the authors wondered if mosquitoes could detect a more reliable directional cue, like infrared radiation.

Within about 10 cm, these insects can detect the heat rising from our skin. And they can directly sense the temperature of our skin once they land. These two senses correspond to two of the three kinds of heat transfer: convection, heat carried away by a medium like air, and conduction, heat via direct touch. But energy from heat can also travel longer distances when converted into electromagnetic waves, generally in the infrared (IR) range of the spectrum. The IR can then heat whatever it hits. Animals like pit vipers can sense thermal IR from warm prey, and the team wondered whether mosquitoes, like Aedes aegypti, could as well.

The researchers put female mosquitoes in a cage and measured their host-seeking activity in two zones. Each zone was exposed to human odors and CO2 at the same concentration that we exhale. However, only one zone was also exposed to IR from a source at skin temperature. A barrier separated the source from the chamber prevented heat exchange through conduction and convection. They then counted how many mosquitoes began probing as if they were searching for a vein.

Adding thermal IR from a 34º Celcius source (about skin temperature) doubled the insects’ host-seeking activity. This makes infrared radiation a newly documented sense that mosquitoes use to locate us. And the team discovered it remains effective up to about 70 cm (2.5 feet).

“What struck me most about this work was just how strong of a cue IR ended up being,” DeBeaubien said. “Once we got all the parameters just right, the results were undeniably clear.”

Previous studies didn’t observe any effect of thermal infrared on mosquito behavior, but senior author Craig Montell suspects this comes down to methodology. An assiduous scientist might try to isolate the effect of thermal IR on insects by only presenting an infrared signal without any other cues. “But any single cue alone doesn’t stimulate host-seeking activity. It’s only in the context of other cues, such as elevated CO2 and human odor that IR makes a difference,” said Montell, the Duggan and Distinguished Professor of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology. In fact, his team found the same thing in tests with only IR: infrared alone has no impact.

A trick for sensing infrared

It isn’t possible for mosquitoes to detect thermal infrared radiation the same way they would detect visible light. The energy of IR is far too low to activate the rhodopsin proteins that detect visible light in animal eyes. Electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength longer than about 700 nanometers won’t activate rhodopsin, and IR generated from body heat is around 9,300 nm. In fact, no known protein is activated by radiation with such long wavelengths, Montell said. But there is another way to detect IR.

Consider heat emitted by the sun. The heat is converted into IR, which streams through empty space. When the IR reaches Earth, it hits atoms in the atmosphere, transferring energy and warming the planet. “You have heat converted into electromagnetic waves, which is being converted back into heat,” Montell said. He noted that the IR coming from the sun has a different wavelength from the IR generated by our body heat, since the wavelength depends on the temperature of the source.

The authors thought that perhaps our body heat, which generates IR, might then hit certain neurons in the mosquito, activating them by heating them up. That would enable the mosquitoes to detect the radiation indirectly.

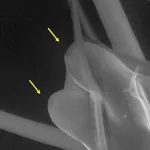

Scientists have known that the tips of a mosquito’s antennae have heat-sensing neurons. And the team discovered that removing these tips eliminated the mosquitoes’ ability to detect IR.

Indeed, another lab found the temperature-sensitive protein, TRPA1, in the end of the antenna. And the UCSB team observed that animals without a functional trpA1 gene, which codes for the protein, couldn’t detect IR.

The tip of each antenna has peg-in-pit structures that are well adapted to sensing radiation. The pit shields the peg from conductive and convective heat, enabling the highly directional IR radiation to enter and warm up the structure. The mosquito then uses TRPA1 — essentially a temperature sensor — to detect infrared radiation.

Diving into the biochemistry

The activity of the heat-activated TRPA1 channel alone might not fully explain the range over which mosquitoes were able to detect IR. A sensor that exclusively relied on this protein may not be useful at the 70 cm range the team had observed. At this distance there likely isn’t sufficient IR collected by the peg-in-pit structure to heat it enough to activate TRPA1.

Fortunately, Montell’s group thought there might be more sensitive temperature receptors based on their previous work on fruit flies in 2011. They had found a few proteins in the rhodopsin family that were quite sensitive to small increases in temperature. Although rhodopsins were originally thought of exclusively as light detectors, Montell’s group found that certain rhodopsins can be triggered by a variety of stimuli. They discovered that proteins in this group are quite versatile, involved not just in vision, but also in taste and temperature sensing. Upon further investigation, the researchers discovered that two of the 10 rhodopsins found in mosquitoes are expressed in the same antennal neurons as TRPA1.

Knocking out TRPA1 eliminated the mosquito’s sensitivity to IR. But insects with faults in either of the rhodopsins, Op1 or Op2, were unaffected. Even knocking out both the rhodopsins together didn’t entirely eliminate the animal’s sensitivity to IR, although it significantly weakened the sense.

Their results indicated that more intense thermal IR — like what a mosquito would experience at closer range (for example, around 1 foot) — directly activates TRPA1. Meanwhile, Op1 and Op2 can get activated at lower levels of thermal IR, and then indirectly trigger TRPA1. Since our skin temperature is constant, extending the sensitivity of TRPA1 effectively extends the range of the mosquito’s IR sensor to around 2.5 ft.

A tactical advantage

Half the world’s population is at risk for mosquito-borne diseases, and about a billion people get infected every year, Chandel said. What’s more, climate change and worldwide travel have extended the ranges of Aedes aegypti beyond tropical and subtropical countries. These mosquitoes are now present in places in the US where they were never found just a few years ago, including California.

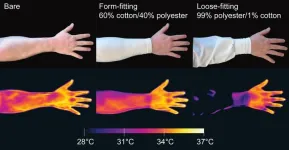

The team’s discovery could provide a way to improve methods for suppressing mosquito populations. For instance, incorporating thermal IR from sources around skin temperature could make mosquito traps more effective. The findings also help explain why loose-fitting clothing is particularly good at preventing bites. Not only does it block the mosquito from reaching our skin, it also allows the IR to dissipate between our skin and the clothing so the mosquitoes cannot detect it.

“Despite their diminutive size, mosquitoes are responsible for more human deaths than any other animal,” DeBeaubien said. “Our research enhances the understanding of how mosquitoes target humans and offers new possibilities for controlling the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases.”

In addition, to the Montell team, Vincent Salgado, formerly at BASF, and his student, Andreas Krumhotz, contributed to this study.

END

Mosquitoes sense infrared from body heat to help track humans down

The recently discovered cue is one of many the insects integrate across various distances

2024-08-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

DOD grants CU researchers $5 Million to study antibiotic-resistant wound infections in Ukraine

2024-08-22

Faculty members in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine have been awarded $5 million by the U.S. Department of Defense to work with partners in Ukraine on clinical and logistical challenges associated with modern large-scale combat operations and prolonged casualty care.

The overarching program — Research and Scalable Infrastructure to Improve Outcomes on the Front Lines of Ukraine by Advancing Treatment and Evaluation (RESOLUTE) — is focusing on collecting data related to antibiotic-resistant wound infections, which have substantially increased amid the military conflict.

The initial project — ...

3D body volume scanner uses AI to help predict metabolic syndrome risk

2024-08-22

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Mayo Clinic researchers are using artificial intelligence (AI) with an advanced 3D body-volume scanner – originally developed for the clothing industry – to help doctors predict metabolic syndrome risk and severity. The combination of tools offers doctors a more precise alternative to other measures of disease risk like body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio, according to findings published in the European Heart Journal - Digital Health.

Metabolic syndrome can lead to heart attack, stroke and other serious health issues and affects over a third of the U.S. population and a quarter of people globally. ...

Building a COMPASS to navigate future pandemics

2024-08-22

Viruses like SARS-CoV-2 don’t respect boundaries, moving between species and continents and leaving destruction as they go. Beating the next pathogen with pandemic potential means getting good at crossing borders ourselves — between fields of study, between research universities, and between scientists and the wider community.

An $18 million grant announced by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) will put that goal within reach. The award brings together five universities and more than 20 researchers, academics, and public health experts to establish the Virginia Tech-led Center ...

Macrophage mix helps determine rate and fate of fatty liver disease

2024-08-22

Formerly known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is an inflammatory disease characterized by liver scarring or fibrosis that progressively impairs liver function.

It is a major risk factor for cirrhosis and liver cancer. And because treatment options are limited, MASH is the second leading cause for liver transplants in the United States after cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis C infection.

A better understanding of the pathological processes that drive MASH is critical to creating effective treatments. In a new paper published ...

Department of Energy announces $36 million to support energy-relevant research in underrepresented regions of America

2024-08-22

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Ensuring that scientific funding goes to states and territories that have typically received smaller fractions of federal research dollars in the past, the Department of Energy (DOE) today announced $36 million in funding for 39 research projects in 19 states via the Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR). The grants connect innovative ideas from scientists at eligible institutions with leading-edge capabilities at the DOE national laboratories.

Supporting scientists while building the expertise and capabilities critical for performing leading research ...

Analysis of 1,500 climate policies reveals only a small fraction achieved significant emission reductions

2024-08-22

A new machine learning analysis has revealed the most effective climate policies out of 1,500 implemented worldwide over the last two decades. Some of the success stories – numbered at about 63 – involve rarely studied policies and unappreciated policy combinations. “Our results provide a clear yet sobering perspective on the policy effort necessary for closing the remaining emissions gap of 23 billion tons carbon dioxide (CO2) by 2023,” write the authors. To achieve the Paris Agreement’s climate targets, it is essential to know which ...

Fatty-acid derived polymers yield recyclable and highly versatile adhesives

2024-08-22

Researchers have presented a new family of polymer adhesives that offer a sustainable and recyclable alternative to conventional polymer adhesives and can be used across a wide range of applications, from industrial adhesives to surgical superglues. The new chemical approach to aLA polymerization addresses the performance and environmental challenges of traditional polymers, providing environmentally friendly adhesive solutions. Polymer adhesives are ubiquitous in modern life and are widely used in many medical, consumer, and industrial products. Given this diversity, each adhesive material is often tailored ...

Governance needed to ensure biosecurity of biological AI models

2024-08-22

Concerns over the biosecurity risks posed by artificial intelligence (AI) models in biology continue to grow. Amid this concern, Doni Bloomfield and colleagues argue, in a Policy Forum, for improved governance and pre-release safety evaluations of new models in order to mitigate potential threats. “We propose that national governments, including the United States, pass legislation and set mandatory rules that will prevent advanced biological models from substantially contributing to large-scale dangers, such as the creation of novel or enhanced pathogens ...

Spontaneous transfer of mitochondrial DNA into the nuclear genomes in the human brain over the individual’s lifespan

2024-08-22

Somatic nuclear mitochondrial DNA (Numt) insertions are mito-nuclear gene transfer events that can arise in the germline and in cancer. This study shows that Numt insertions arise spontaneously and accumulate in brain tissues during development or over the human lifespan.

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002723

Article Title: Somatic nuclear mitochondrial DNA insertions are prevalent in the human brain and accumulate over time in fibroblasts

Author Countries: United States

Funding: see manuscript END ...

Cancer drug could treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, study shows

2024-08-22

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A type of drug developed for treating cancer holds promise as a new treatment for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, according to a recent study by researchers at Penn State, Stanford University and an international team of collaborators.

The researchers discovered that by blocking a specific enzyme called indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1, or IDO1 for short, they could rescue memory and brain function in models that mimic Alzheimer’s disease. The findings, published today (Aug. 22) in the journal Science, suggest that IDO1 inhibitors currently ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

[Press-News.org] Mosquitoes sense infrared from body heat to help track humans downThe recently discovered cue is one of many the insects integrate across various distances