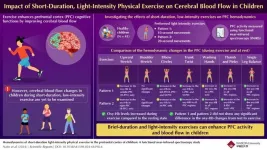

(Press-News.org) Cognitive functions, also known as intellectual functions, encompass thinking, understanding, memory, language, computation, and judgment, and are performed in the cerebrum. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), located in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex, handles these functions. Studies have shown that exercise improves cognitive function through mechanisms such as enhanced cerebral blood flow, structural changes in the brain, and promotion of neurogenesis. However, 81% of children globally do not engage in enough physical activity, leading to high levels of sedentary behavior and insufficient exercise. This lack of physical activity raises concerns about its negative impact on children's healthy brain development and cognitive function.

A recent study published on July 6, 2024, in Volume 14 of Scientific Reports, by doctoral student Takashi Naito from the Graduate School of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, along with Professors Kaori Ishii and Koichiro Oka from the Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, offers insights into potential solutions. The study investigated the effects of short-duration and light-intensity exercise on increasing cerebral blood flow in children. “Our goal is to develop a light-intensity exercise program that is accessible to everyone, aiming to enhance brain function and reduce children's sedentary behavior. We hope to promote and implement this program in schools through collaborative efforts,” says Naito.

To enhance cognitive performance, it is essential to develop exercise programs that increase cerebral blood flow. While previous studies have established the benefits of moderate-to-vigorous exercise on cognitive functions, changes in cerebral blood flow during light-intensity exercise, particularly in children, is yet to be investigated. To address this gap, the team conducted an experimental study to examine the effects of short-term, light-intensity exercises on prefrontal cortex (PFC) hemodynamics. They focused on exercises that can be easily performed on the spot without special equipment, such as stretching. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), an imaging technique that measures changes in cerebral blood flow through oxy-Hb concentrations, was used for this purpose.

The study enrolled 41 healthy children ranging from fifth-grade elementary to third-year junior high school students. The children were taught seven different types of low-intensity exercises along with associated safety measures. These exercises included Upward Stretch, Shoulder Stretch, Elbow Circles, Trunk Twist, Washing Hands, Thumb and Pinky, and Single-leg Balance. The exercises were performed while seated except Single-leg Balance, with movement patterns lasting for 10 and 20 seconds. Researchers recorded and compared oxy-Hb levels at rest and during exercise.

The study's results were highly promising, showing a significant increase in oxy-Hb levels in multiple regions of the PFC during all forms of exercise compared to the resting state. However, no significant change in oxy-Hb levels was observed during static stretching with movement in one direction. "By combining the types of exercise that easily increase blood flow in the PFC identified in this study, it is possible to develop an exercise program that everyone can easily engage in to improve children's executive functions. It may also be used in the future to prevent cognitive decline in adults and the elderly," explains Naito optimistically.

In conclusion, this groundbreaking study represents a significant step forward in combating sedentary lifestyles and activating brain functions in children, thereby supporting their physical and mental growth. Although this study demonstrated that even short-duration, low-intensity exercise can increase cerebral blood flow in the prefrontal cortex, future research is needed to confirm whether such exercises actually lead to improved cognitive function.

***

Reference

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-66598-6

Authors: Takashi Naito1,2, Koichiro Oka3, and Kaori Ishii3

Affiliations

1Graduate School of Sport Sciences, Waseda University

2Organization for the Strategic Coordination of Research and Intellectual Properties, Meiji University

3Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University

About Waseda University

Located in the heart of Tokyo, Waseda University is a leading private research university that has long been dedicated to academic excellence, innovative research, and civic engagement at both the local and global levels since 1882. The University has produced many changemakers in its history, including nine prime ministers and many leaders in business, science and technology, literature, sports, and film. Waseda has strong collaborations with overseas research institutions and is committed to advancing cutting-edge research and developing leaders who can contribute to the resolution of complex, global social issues. The University has set a target of achieving a zero-carbon campus by 2032, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations in 2015.

To learn more about Waseda University, visit https://www.waseda.jp/top/en

About Takashi Naito

Takashi Naito is a doctoral student at the Graduate School of Sport Sciences, Waseda University. He holds a Master’s in Sport Sciences from Waseda University with a focus on physical activity, sedentary behavior, cognitive function, and fNIRS. His career includes roles as a part-time lecturer at Surugadai University and a researcher at Meiji University. Naito has received awards for his research and has published extensively on exercise and cognitive health, including studies on light-intensity exercise and its impact on children. He is a member of the Japanese Association of Exercise Epidemiology (JAEE) and the Japanese Society of Health Education and Promotion.

END

Austocystin D, a natural compound produced by fungi, has been recognized for its cytotoxic effects and anticancer activity in various cell types. It exhibits potent activity even in cells that express proteins associated with multidrug resistance, attracting significant global research interest. Austocystin D promotes cell death by damaging their DNA, a process which might be dependent on cytochrome P450 (CYP) oxygenase enzymes. Notably, austocystin D has shown significant activity against cancer cells with increased CYP expression. However, the specific role and function of the CYP2J2 enzyme in the cytotoxicity of austocystin D remain ...

Research Highlights:

People diagnosed with unruptured cerebral aneurysms (weakened areas in brain blood vessels) who are being monitored without treatment have a higher risk of developing mental illness compared to those who have not been diagnosed with a cerebral aneurysm. The largest impact was among adults younger than age 40.

The study conducted in South Korea found that the psychological burden caused by the diagnosis of an unruptured aneurysm may contribute to the development of mental health conditions, such as anxiety, stress, depression, eating ...

A new Nature Human Behaviour study, jointly led by Dr Margherita Malanchini at Queen Mary University of London and Dr Andrea Allegrini at University College London, has revealed that non-cognitive skills, such as motivation and self-regulation, are as important as intelligence in determining academic success. These skills become increasingly influential throughout a child's education, with genetic factors playing a significant role. The research, conducted in collaboration with an international team of experts, suggests that fostering non-cognitive skills alongside cognitive abilities could significantly improve educational ...

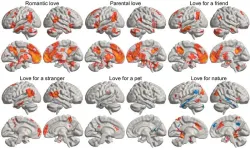

We use the word ‘love’ in a bewildering range of contexts — from sexual adoration to parental love or the love of nature. Now, more comprehensive imaging of the brain may shed light on why we use the same word for such a diverse collection of human experiences.

‘You see your newborn child for the first time. The baby is soft, healthy and hearty — your life’s greatest wonder. You feel love for the little one.’

The above statement was one of many simple scenarios presented to fifty-five parents, self-described as being in a loving relationship. Researchers from Aalto University utilised ...

Researchers from the Institute of Process Engineering (IPE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have developed a sustainable, biodegradable, biorecyclable material: high-entropy non-covalent cyclic peptide (HECP) glass. This innovative glass features enhanced crystallization-resistance, improved mechanical properties, and increased enzyme tolerance, laying the foundation for its application in pharmaceutical formulations and smart functional materials. This study was published in Nature Nanotechnology on ...

Malaria is caused by a eukaryotic microbe of the Plasmodium genus, and is responsible for more deaths than all other parasitic diseases combined. In order to transmit from the human host to the mosquito vector, the parasite has to differentiate to its sexual stage, referred to as the gametocyte stage. Unlike primary sex determination in mammals, which occurs at the chromosome level, it is not known what causes this unicellular parasite to form males and females. New research at Stockholm University has implemented high-resolution genomic tools to map the global repertoire of genes ...

Climate scientists have long agreed that humans are largely responsible for climate change. However, people often do not realize how many scientists share this view. A new 27-country study published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour finds that communicating the consensus among scientists can clear up misperceptions and strengthen beliefs about climate change.

The study is co-led by Bojana Većkalov at the University of Amsterdam and Sandra Geiger of the University of Vienna. Kai Ruggeri, professor of health policy and management at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

Scientific consensus identifying humans as primarily ...

Artificial intelligence (AI) has practically limitless applications in healthcare, ranging from auto-drafting patient messages in MyChart to optimizing organ transplantation and improving tumor removal accuracy. Despite their potential benefit to doctors and patients alike, these tools have been met with skepticism because of patient privacy concerns, the possibility of bias, and device accuracy.

In response to the rapidly evolving use and approval of AI medical devices in healthcare, a multi-institutional team of researchers at the UNC School of Medicine, Duke University, Ally Bank, Oxford University, Colombia University, and University of Miami have been on a mission to build ...

High levels of traffic-related air pollutants have been linked with elevated risks of developing cancer and other diseases. New research indicates that multiple aspects of structural racism—the ways in which societal laws, policies, and practices systematically disadvantage certain racial or ethnic groups—may contribute to increased exposure to carcinogenic traffic-related air pollution. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Most studies suggesting that structural racism, which encompasses factors such as residential segregation and differences in economic status and homeownership, may influence ...

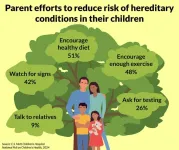

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Among things many families don’t wish to pass down to their children and grandchildren: medical issues.

One in five parents say their child has been diagnosed with a hereditary condition, while nearly half expressed concerns about their child potentially developing such a condition, a new national poll suggests.

And two thirds of parents want their healthcare provider to suggest ways to prevent their child from developing a health problem that runs in the family, according to the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National ...