(Press-News.org) In a study that reshapes what we know about COVID-19 and its most perplexing symptoms, scientists have discovered that the blood coagulation protein fibrin causes the unusual clotting and inflammation that have become hallmarks of the disease, while also suppressing the body’s ability to clear the virus.

Importantly, the team also identified a new antibody therapy to combat all of these deleterious effects.

Published in Nature, the study by Gladstone Institutes and collaborators overturns the prevailing theory that blood clotting is merely a consequence of inflammation in COVID-19. Through experiments in the lab and with mice, the researchers show that blood clotting is instead a primary effect, driving other problems—including toxic inflammation, impaired viral clearance, and neurological symptoms prevalent in those with COVID-19 and long COVID.

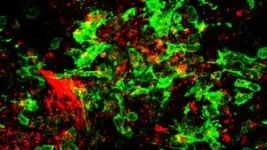

The trigger is fibrin, a protein in the blood that normally enables healthy blood coagulation, but has previously been shown to have toxic inflammatory effects. In the new study, scientists found that fibrin becomes even more toxic in COVID-19 as it binds to both the virus and immune cells, creating unusual clots that lead to inflammation, fibrosis, and loss of neurons.

“Knowing that fibrin is the instigator of inflammation and neurological symptoms, we can build a new path forward for treating the disease at the root,” says Katerina Akassoglou, PhD, a senior investigator at Gladstone and the director of the Center for Neurovascular Brain Immunology at Gladstone and UC San Francisco. “In our experiments in mice, neutralizing blood toxicity with fibrin antibody therapy can protect the brain and body after COVID infection.”

From the earliest months of the pandemic, irregular blood clotting and stroke emerged as puzzling effects of COVID-19, even among patients who were otherwise asymptomatic. Later, as long COVID became a major public health issue, the stakes grew even higher to understand the cause of this disease’s other symptoms, including its neurological effects. More than 400 million people worldwide have had long COVID since the start of the pandemic, with an estimated economic cost of about $1 trillion each year.

Flipping the Conversation

Many scientists and medical professionals have hypothesized that inflammation from the immune system’s rapid reaction to the COVID-causing virus is what leads to blood clotting and stroke. But even at the dawn of the pandemic in 2020, that explanation didn’t sound right to Akassoglou and her scientific collaborators.

“We know of many other viruses that unleash a similar cytokine storm in response to infection, but without causing blood clotting activity like we see with COVID,” says Warner Greene, MD, PhD, senior investigator and director emeritus at Gladstone, who co-led the study with Akassoglou.

“We began to wonder if blood clots played a principal role in COVID—if this virus evolved in a way to hijack clotting for its own benefit,” Akassoglou adds.

Indeed, through multiple experiments in mice, the researchers found that the virus spike protein directly binds to fibrin, causing structurally abnormal blood clots with enhanced inflammatory activity. The team leveraged genetic tools to create a specific mutation that blocks only the inflammatory properties of fibrin without affecting the protein’s beneficial blood-clotting abilities.

When mice were genetically altered to carry the mutant fibrin or had no fibrin in their bloodstream, the scientists found that inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and clotting in the lungs didn’t occur or were much reduced after COVID-19 infection.

In addition to discovering that fibrin sets off inflammation, the team made another important discovery: fibrin also suppresses the body’s “natural killer,” or NK, cells, which normally work to clear the virus from the body. Remarkably, when the scientists depleted fibrin in the mice, NK cells were able to clear the virus.

These findings support that fibrin is necessary for the virus to harm the body.

Mechanism Not Triggered by Vaccines

The fibrin mechanism described in the paper is not related to the extremely rare thrombotic complication with low platelets that has been linked to adenoviral DNA COVID-19 vaccines, which are no longer available in the U.S.

By contrast, in a study of 99 million COVID-vaccinated individuals led by The Global COVID Vaccine Safety Project, vaccines that leverage mRNA technology to produce spike proteins in the body exhibited no excessive clotting or blood-based disorders that met the threshold for safety concerns. Instead, mRNA vaccines protect from clotting complications otherwise induced by infection.

Protecting the Brain

Akassoglou’s lab has long investigated how fibrin that leaks into the brain triggers neurologic diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis, essentially by hijacking the brain’s immune system and setting off a cascade of harmful, often irreversible, effects.

The team now showed that in COVID-infected mice, fibrin is responsible for the harmful activation of microglia, the brain’s immune cells involved in neurodegeneration. After infection, the scientists found fibrin together with toxic microglia and when they inhibited fibrin, the activation of these toxic cells in the brains of mice was significantly reduced.

“Fibrin that leaks into the brain may be the culprit for COVID-19 and long COVID patients with neurologic symptoms, including brain fog and difficulty concentrating,” Akassoglou says. “Inhibiting fibrin protects neurons from harmful inflammation after COVID-19 infection.”

The team tested its approach on different strains of the virus that causes COVID-19, including those that can infect the brain and those that do not. Neutralizing fibrin was beneficial in both types of infection, pointing to the harmful role of fibrin in brain and body in COVID-19 and highlighting the broad implications of this study.

A New Potential Therapy

This study demonstrates that fibrin is damaging in at least two ways: by activating a chronic form of inflammation and by suppressing a beneficial NK cell response capable of clearing virally infected cells.

“We realized if we could neutralize both of these negative effects, we could potentially resolve the severe symptoms we’re seeing in patients with COVID-19 and possibly long COVID,” Greene says.

Akassoglou’s lab previously developed a drug, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody, that acts only on fibrin’s inflammatory properties without adverse effects on blood coagulation and protects mice from multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease.

In the new study, the team showed that the antibody blocked the interaction of fibrin with immune cells and the virus. By administering the immunotherapy to infected mice, the team was able to prevent and treat severe inflammation, reduce fibrosis and viral proteins in the lungs, and improve survival rates. In the brain, the fibrin antibody therapy reduced harmful inflammation and increased survival of neurons in mice after infection.

A humanized version of Akassoglou’s first-in-class fibrin-targeting immunotherapy is already in Phase 1 safety and tolerability clinical trials in healthy people by Therini Bio. The drug cannot be used on patients until it completes this Phase 1 safety evaluation, and then would need to be tested in more advanced trials for COVID-19 and long COVID.

Looking ahead to such trials, Akassoglou says patients could be selected based on levels of fibrin products in their blood—a measure believed to be a predictive biomarker of cognitive impairment in long COVID.

“The fibrin immunotherapy can be tested as part of a multipronged approach, along with prevention and vaccination, to reduce adverse health outcomes from long COVID,” Greene adds.

The Power of Team Science

The study’s findings intersect the scientific areas of immunology, hematology, virology, neuroscience, and drug discovery—and required many labs across institutions to work together to execute experiments required to solve the blood-clotting mystery. Akassoglou founded the Center for Neurovascular Brain Immunology at Gladstone and UCSF in 2021 specifically for the purpose of conducting multidisciplinary, collaborative studies that address complex problems.

“I don’t think any single lab could have accomplished this on their own,” says Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology and co-author of the study, noting important contributions from teams at Stanford, UC San Francisco, UC San Diego, and UCLA. “This tour-de-force study highlights the importance of collaboration in tackling these big questions.”

Not only did this study address a big question, but it did so in a way that paves a clear clinical path for helping patients who have few options today, says Lennart Mucke, MD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease.

“Neurological symptoms of COVID-19 and long COVID can touch every part of a person’s life, affecting cognitive function, memory, and even emotional health,” Mucke says. “This study presents a novel strategy for treating these devastating effects and addressing the long-term disease burden of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.”

END

Discovery of how blood clots harm brain and body in COVID-19 points to new therapy

Scientists at Gladstone Institutes, along with collaborators, have solved the mystery of unusual blood clotting and inflammation in COVID-19—and identified a promising therapeutic strategy.

2024-08-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

JAMA review highlights advances in kidney cancer research and care

2024-08-28

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina — New insights into the biology of kidney cancer, including those informed by scientific discoveries that earned a Nobel Prize, have led to advances in treatment and increased survival rates, according to a review by UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center’s William Kim, MD, and Tracy Rose, MD, MPH.

Their observations, drawn from a meta-analysis of 89 studies published between January 2013 and January 2024, were published in JAMA Aug. 28.

“The Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 2019 was awarded ...

new diabetes research in Scientific Reports links blood glucose levels and voice

2024-08-28

NEW YORK/TORONTO – August 28, 2024 – As part of its ongoing exploration of vocal biomarkers and the role they can play in enhancing health outcomes, Klick Labs published a new study in Scientific Reports today – confirming the link between blood glucose levels and voice pitch and opening the door to future advancements in non-invasive glucose monitoring for people living with Type 2 diabetes.

In “Linear Effects of Glucose Levels on Voice Fundamental Frequency in Type 2 diabetes and Individuals with Normoglycemia,” researchers ...

Augmented recognition of distracted driving state based on electrophysiological analysis of brain network

2024-08-28

A research paper by scientists at Beijing Jiaotong University proposed an electrophysiological analysis-based brain network method for the augmented recognition of different types of distractions during driving.

The new research paper, published on Jul. 04 in the journal Cyborg and Bionic Systems, designed and conducted a simulated experiment comprising 4 distracted driving subtasks. Three connectivity indices, including both linear and nonlinear synchronization measures, were chosen to construct the brain network. By computing connectivity strengths and topological features, we explored the potential relationship between brain network configurations and states ...

The functions of actin-binding proteins are regulated by the flexibility and specific helical twists of actin filaments

2024-08-28

Researchers at Kanazawa University report in eLife on deciphering the actin structure-dependent preferential cooperative binding of cofilin.

The actin filament is a double-stranded helical structure formed by intertwining two long-pitch helices, with the distance between crossover points, known as the half helical pitch (HHP), being about 36 nm. A canonical half helix consists of 13 actin protomers, or 6.5 protomer pairs, resulting in a mean axial distance (MAD) of 5.5 nm between two adjacent protomers ...

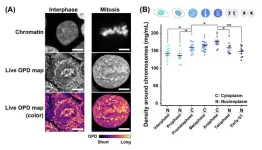

Team discovers transient rise in depletion attraction contributes to mitotic chromosome condensation

2024-08-28

A team of scientists studying cell division developed a special light microscopy system and used it to analyze the molecular density of cellular environments. Their results provide a novel insight into mitotic chromosome condensation in living human cells.

Their work is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on August 27, 2024.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2403153121

To carry out their study, the team developed an orientation-independent-differential interference contrast (OI-DIC) microscopy system combined with a confocal ...

nTIDE Deeper Dive August 2024: Disability Employment Disparities Among Students: High School Struggles, College Advancement

2024-08-28

East Hanover, NJ – August 28, 2024 – Young people with disabilities aged 16 to 24 had high school enrollment rates nearly identical to their non-disabled peers, but significantly fewer held jobs during this time. Meanwhile, college students with disabilities were less likely to be enrolled but were slightly more likely to be employed, possibly benefiting from the rise of remote work opportunities in the post-COVID era, according to data shared during the according to last Friday’s National Trends in Disability ...

Rain or shine? How rainfall impacts size of sea turtle hatchlings

2024-08-28

Female sea turtles lay their eggs, cover the nest with sand and then return to the ocean, leaving them to develop and hatch on their own. From nest predators to rising temperatures, odds of survival are bleak. Once hatched and in the ocean, about one in 1,000 make it to adulthood.

Hatchling size matters. Larger hatchlings, which move faster, are more likely to survive because they spend less time on risky beach sands.

Research shows that both air and sand temperatures crucially impact sea turtle hatchlings. Cooler temperatures produce larger, heavier hatchlings with more males, while warmer temperatures ...

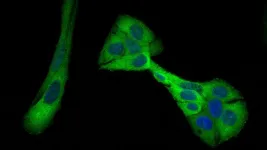

How breast cancer goes hungry

2024-08-28

Cancer cells have voracious appetites. And there are certain nutrients they can’t live without. Scientists have long hoped they might stop tumors in their tracks by cutting off an essential part of cancer cells’ diet. But these cells are crafty and often find a new way to get what they need. How? By reprogramming their metabolism and switching to backup food supplies.

Now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Assistant Professor Michael Lukey has found a way to deprive cancer cells of both a vital nutrient and their backup supply. In lab experiments with breast cancer cells, patient-derived tissue models, and mice, ...

Are English teachers in Japan ready to teach students with disabilities?

2024-08-28

Access to education is recognized as one of the pillars of sustainability; it is certainly a necessary foundation if we are to build a better world for ourselves and future generations. However, education needs to be not only accessible, but also inclusive. That is, it should extend to people with all kinds of disabilities and suit their particular needs.

According to a recent report by the World Health Organization, it is estimated that a striking 16% of the world’s population lives with some form of disability. Considering there are about 1.5 billion English language teachers (ELTs) worldwide, there is a great need for adequately trained ELTs that can teach students with ...

Aging population: Public willingness to pay for healthcare hinges on perceived benefits and risks

2024-08-28

Healthcare is undoubtedly crucial for everyone. As individuals age, the risk for health issues and related expenses increases. Consequently, many countries have universal healthcare systems, primarily funded through tax and insurance, to ensure access to essential healthcare services. However, this system is under a heavy fiscal burden since the aging population has increased manyfold, owing to decreasing fertility rates and increasing life span. To sustain the system, governments must face the herculean task of persuading citizens to contribute more to health insurance.

In a recent study, a research team consisting of Associate ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

New study finds deep ocean microbes already prepared to tackle climate change

ARLIS partners with industry leaders to improve safety of quantum computers

Modernization can increase differences between cultures

Cannabis intoxication disrupts many types of memory

[Press-News.org] Discovery of how blood clots harm brain and body in COVID-19 points to new therapyScientists at Gladstone Institutes, along with collaborators, have solved the mystery of unusual blood clotting and inflammation in COVID-19—and identified a promising therapeutic strategy.