(Press-News.org) An ancient gene is crucial for the development of the distinctive waist that divides the spider body plan in two, according to a study publishing August 29th in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Emily Setton from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US, and colleagues.

The spider body is divided into two sections, separated by a narrow waist. Compared to insects and crustaceans, relatively little is known about embryonic development in spiders, and the genes involved in the formation of the spider waist are poorly understood.

To investigate, researchers sequenced genes expressed in embryos of the Texas brown tarantula (Aphonopelma hentzi) at different stages of development. They identified 12 genes that are expressed at different levels in embryonic cells on either side of the waist. They silenced each of these candidate genes, one by one, in embryos of the common house spider (Parasteatoda tepidariorum) to understand their function in development. This revealed one gene — which the authors named ‘waist-less’ — that is required for the development of the spider waist. It is part of a family of genes called ‘Iroquois’, which have previously been studied in insects and vertebrates. However, an analysis of the evolutionary history of the Iroquois family suggests that waist-less was lost in the common ancestor of insects and crustaceans. This might explain why waist-less had not been studied previously, because research has tended to focus on insect and crustacean model organisms that lack the gene.

The results demonstrate that an ancient, but previously unstudied gene is critical for the development of the boundary between the front and rear body sections, which is a defining characteristic of chelicerates — the group that includes spiders and mites. Further research is needed to understand the role of waist-less in other chelicerates, such as scorpions and harvestman, the authors say.

The authors add, “Our work identified a new and unexpected gene involved in patterning the iconic spider body plan. More broadly, this work highlights the function of new genes in ancient groups of animals.”

An ancient gene is crucial for the development of the distinctive waist that divides the spider body plan in two, according to a study publishing August 29th in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Emily Setton from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US, and colleagues.

The spider body is divided into two sections, separated by a narrow waist. Compared to insects and crustaceans, relatively little is known about embryonic development in spiders, and the genes involved in the formation of the spider waist are poorly understood.

To investigate, researchers sequenced genes expressed in embryos of the Texas brown tarantula (Aphonopelma hentzi) at different stages of development. They identified 12 genes that are expressed at different levels in embryonic cells on either side of the waist. They silenced each of these candidate genes, one by one, in embryos of the common house spider (Parasteatoda tepidariorum) to understand their function in development. This revealed one gene — which the authors named ‘waist-less’ — that is required for the development of the spider waist. It is part of a family of genes called ‘Iroquois’, which have previously been studied in insects and vertebrates. However, an analysis of the evolutionary history of the Iroquois family suggests that waist-less was lost in the common ancestor of insects and crustaceans. This might explain why waist-less had not been studied previously, because research has tended to focus on insect and crustacean model organisms that lack the gene.

The results demonstrate that an ancient, but previously unstudied gene is critical for the development of the boundary between the front and rear body sections, which is a defining characteristic of chelicerates — the group that includes spiders and mites. Further research is needed to understand the role of waist-less in other chelicerates, such as scorpions and harvestman, the authors say.

The authors add, “Our work identified a new and unexpected gene involved in patterning the iconic spider body plan. More broadly, this work highlights the function of new genes in ancient groups of animals.”

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002771

Citation: Setton EVW, Ballesteros JA, Blaszczyk PO, Klementz BC, Sharma PP (2024) A taxon-restricted duplicate of Iroquois3 is required for patterning the spider waist. PLoS Biol 22(8): e3002771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002771

Author Countries: United States

Funding: This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (IOS-1552610 and IOS-2016141 to PPS) (nsf.gov). Additional support to EVWS came from The National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1747503 to EVWS) (nsf.gov). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

END

A new study paves the way to understanding biotic recovery after an ecological crisis in the Mediterranean Sea about 5.5 million years ago. An international team led by Konstantina Agiadi from the University of Vienna has now been able to quantify how marine biota was impacted by the salinization of the Mediterranean: Only 11 percent of the endemic species survived the crisis, and the biodiversity did not recover for at least another 1.7 million years. The study was just published in the renowned journal Science.

Lithospheric movements throughout Earth history have repeatedly led to the isolation of regional seas from the ...

Staphylococcus aureus has the potential to develop durable vancomycin resistance, according to a study published August 28, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS Pathogens by Samuel Blechman and Erik Wright from the University of Pittsburgh, USA.

Despite decades of widespread treatment with the antibiotic vancomycin, vancomycin resistance among the bacterium S. aureus is extremely uncommon—only 16 such cases have reported in the U.S. to date. Vancomycin resistance mutations enable bacteria to grow in the presence of vancomycin, but they do so at a cost. Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) strains grow more slowly and will often lose their resistance mutations if vancomycin ...

A person’s exhaled breath – which provides information that could unveil diverse health insights – has been hard to analyze. Now, a novel “smart mask” provides real-time, non-invasive monitoring of what people exhale. The mask, dubbed EBCare, captures and analyzes exhaled breath condensate (EBC), and it offers a promising solution for continuous EBC analysis at an affordable cost. “The significance of EBCare lies in its role as a versatile, convenient, efficient, real-time research platform and solution in various medical domains, ...

Challenging long-held beliefs that bird nest building is solely influenced by genetics or the environment, researchers report that the white-browed sparrow weavers of the Kalahari Desert, Africa, build nests with distinct architectural styles that reflect group-specific cultural traditions. “Behavioral traditions in birds have been well documented for song, migration, foraging, and tool use. Here, we add building behavior and show that architectural styles emerge from birds that build together,” write the ...

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) from mitochondria are key drivers of genetic chaos in cancer by causing the collapse of micronuclear envelopes, a process that fuels the chromosomal instability (CIN) often observed in aggressive tumor behavior. These are the findings of two new studies. The findings identify key proteins in this destructive process – p62 and CHMP7 – revealing potential prognostic markers and therapeutic targets for high-CIN tumors. Errors in chromosome segregation during cell division can lead to chromosomal instability, a key feature of cancer. These errors result in the formation of micronuclei, which are small structures ...

A meta-analysis of Mediterranean Sea marine species reveals the profound impact of the Messinian Salinity Crisis – a drastic environmental event that resulted in the almost complete evaporation of the Mediterranean Sea roughly 5.5 million years ago. According to the new study’s findings, the event nearly reset the region’s biodiversity. The findings offer novel insights linking tectonic and palaeoceanographic changes to marine biodiversity, highlighting the significant role of salt giants in shaping biogeographic patterns, including those that still influence ecosystems today. The Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC), ...

New study from Hebrew University reveals that marmoset monkeys use specific calls, known as "phee-calls," to name each other, a behavior previously known to exist only in humans, dolphins, and elephants. This discovery highlights the complexity of social communication in marmosets and suggests that their ability to vocally label each other may provide valuable insights into the evolution of human language.

LINK to pictures https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1VjzO-70hk27UVX_IuQ6FTsHgmCgk9PCH?usp=drive_link

Credit for pictures and sound: David Omer Lab

In a groundbreaking discovery, researchers from Hebrew ...

Personalized wearable devices that monitor people's health are on the rise. From watches to patches and other types of sensors, these smart devices can monitor heart activity, inflammation levels, and more to help patients better manage their health from their own homes. Now, a new type of wearable device can be added to the list: a high-tech paper mask that monitors one's breath.

Caltech's Wei Gao, professor of medical engineering, and his colleagues have developed a ...

In a study published in Science, researchers at Karolinska Institutet describe the neural processes behind how morphine relieves pain. This is valuable knowledge because the drug has such serious side effects.

Morphine is a powerful painkiller that belongs to the group of opioids. It blocks signals in the pain pathways and also increases feelings of pleasure.

Morphine acts on several central and peripheral pain pathways in the body, but the neural processes behind the pain relief have not previously been fully understood.

Researchers have now investigated how morphine relieves pain using ...

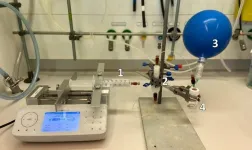

Chemists at the University of Amsterdam have developed a method to furnish a range of molecules with a trifluoromethyl group attached to a sulphur, nitrogen or oxygen atom. Their procedure, which has just been published in Science, avoids the use of PFAS reagents. It thus provides an environmentally friendly synthesis route for pharmaceutical and agrochemical compounds that rely on the presence of the trifluoromethyl group.

The straightforward and effective method was developed at the Flow Chemistry group at the Van ‘t Hoff Institute for Molecular Sciences ...