(Press-News.org)

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men worldwide, following lung cancer. In the United States alone, nearly 300,000 new cases are diagnosed annually. While reducing testosterone and other male hormones can be an effective treatment for prostate cancer, this approach becomes ineffective once the disease progresses to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). At this stage, the cancer advances quickly and becomes resistant to conventional hormonal therapies and chemotherapy.

A clever strategy for fighting mCRPC is to exploit the fact that these tumor cells usually overexpress a membrane protein called prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). In particular, targeted alpha therapy involves attaching a radioactive atom like actinium-225 (225Ac) to a compound that binds strongly to PSMA. As the radioactive atom decays, it emits alpha particles that are harmful to nearby cells—in this case, tumor cells. However, given that the production of 225Ac is very low, scientists are looking for more viable alternatives.

In a recent study, a research team led by Professor Tomoya Uehara from Chiba University, Japan, developed a novel compound for the targeted alpha therapy of prostate cancer using a different alpha particle emitting radionuclide: astatine-211 (211At). Other members of the team included Hiroyuki Suzuki and Kento Kannaka from Chiba University, as well as Kazuhiro Takahashi from Fukushima Medical University. Their findings, which were published in Volume 9 of EJNMMI Radiopharmacy and Chemistry on June 17, 2024, address one of the main issues plaguing 211At-based compounds for targeted alpha therapy: deastatination.

Simply put, deastatination refers to the natural process by which enzymes in the body cleave the 211At atom from the whole compound, effectively splitting the therapeutic part from the PSMA-targeting part. This not only renders the drug unable to address the cancer itself, but also releases a radioactive payload to other tissues in the body, which can damage the liver, stomach, and kidneys.

To avoid this problem, the researchers turned to a chemical structure they had previously studied. “Recently, we developed a neopentyl derivative with two hydroxy groups, which we referred to as an ‘NpG structure,’ as a 211At-labeling moiety that could stably retain 211At in vivo,” explains Uehara, “Based on these past results, we hypothesized that the NpG structure could be used to design a variety of 211At-labeled PSMA-targeting derivatives.”

The team put their theory to the test by designing and synthesizing a pair of such derivatives, each containing a different glutamic acid linker between the NpG structure and the PSMA-targeting region, namely asymmetric urea. These compounds were named NpG-L-PSMA and NpG-D-PSMA.

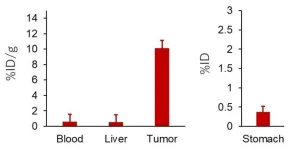

First, the researchers ran tests using iodine-125 (125I) bound to these compounds rather than 211At, given that 125I is more abundant and easier to procure. Through experiments in mice bearing tumors from a human prostate cancer cell line, they found that both [125I]I-NpG-D-PSMA and [125I]I-NpG-L-PSMA exhibited low accumulation in the stomach and thyroid, hinting at their high in vivo stability against deiodination. However, [125I]I-NpG-D-PSMA showed higher accumulation in tumor tissue than [125I]I-NpG-L-PSMA.

Thus, the team proceeded to run another series of experiments, now using [211At]At-NpG-D-PSMA. Just like its iodine-containing counterpart, this compound exhibited high accumulation in tumors and low accumulation in vital organs such as the liver and stomach.

Taken together, the results of these in vivo experiments highlight the potential of NpG-D-PSMA for targeted alpha therapy. “Our study showed that the neopentyl glycol structure, which can stably hold radiohalogens like 211At and 125I in vivo, may be applicable as a tumor-targeting agent. The use of the neopentyl glycol structure as a radiohalogen labeling moiety could enable the production of nuclear medicines for various types of tumors, thereby contributing greatly to human welfare,” concludes Uehara.

With any luck, further developments in this field will soon extend our arsenal against challenging metastatic cancers, lighting a beacon of hope for those affected.

About Professor Tomoya Uehara

Tomoya Uehara is a Principal Investigator and Professor at the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chiba University. He specializes in the study and development of radiopharmaceuticals, both for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, using techniques from analytical and physical chemistry. He has published over 80 peer-reviewed papers on these topics, and he is a member of the Japan Society of Nuclear Medicine, The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan, and the Japan Society for Molecular Imaging.

END

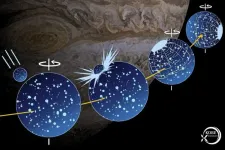

Around 4 billion years ago, an asteroid hit the Jupiter moon Ganymede. Now, a Kobe University researcher realized that the Solar System's biggest moon's axis has shifted as a result of the impact, which confirmed that the asteroid was around 20 times larger than the one that ended the age of the dinosaurs on Earth, and caused one of the biggest impacts with clear traces in the Solar System.

Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System, bigger even than the planet Mercury, and is also interesting for the liquid water oceans beneath its icy surface. Like the Earth’s moon, it is tidally locked, meaning that it always shows the ...

A sweat-powered wearable has the potential to make continuous, personalized health monitoring as effortless as wearing a Band-Aid. Engineers at the University of California San Diego have developed an electronic finger wrap that monitors vital chemical levels—such as glucose, vitamins, and even drugs—present in the same fingertip sweat from which it derives its energy.

The advance was published Sept. 3 in Nature Electronics by the research group of Joseph Wang, a professor in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering ...

Who killed the pregnant porbeagle?

In a marine science version of the game Cluedo, researchers from the US have now accused a larger shark, with its deciduous triangular teeth, in the open sea southwest of Bermuda. This scientific whodunnit is published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

“This is the first documented predation event of a porbeagle shark anywhere in the world,” said lead author Dr Brooke Anderson, a former graduate student at Arizona State University.

“In one event, the population not only lost a reproductive female that could contribute to population growth, but it also lost all her developing ...

Belching is a common bodily function, but when it escalates to a level that interferes with daily life, it is defined as belching disorders. International surveys have reported that approximately 1% of adults have belching disorders, but the percentage in Japan and the factors involved often elude medical professionals.

To examine the relationship between the rate of belching disorders, comorbidities, and lifestyles in Japan, a research team led by Professor Yasuhiro Fujiwara of Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Medicine ...

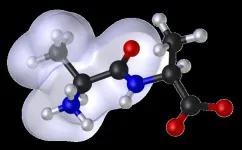

Scientists from China have investigated how short peptide chains aggregate together in order to deepen our understanding of the process, which is crucial for drug stability and material development. Their study, published in JACS Au, provides valuable insights into how short proteins called peptides interact, fold, and function. These findings have significant implications for medicine, material science, and biotechnology.

Peptides are short chains of amino acids that play essential roles in the body by building structures, speeding up chemical reactions, and supporting our immune system. The specific function of a protein is determined by how its amino acids interact with each other and ...

A national survey conducted as part of University of Exeter research has found huge variation in treatment for ADHD, highlighting the struggle many young adults face once they turn 18.

Researchers have warned that the current system is failing many young adults as they transition from children’s to adult’s services - suddenly finding themselves unable to access treatment because services do not link up effectively.

More than 750 people from across the country – including commissioners, healthcare professionals working ...

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 2 September 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. ...

Early detection of breast cancer through mammography screening continues to save lives. However, abnormal findings on mammograms can lead to women being recalled for additional imaging and biopsies, many of which turn out to be “false positives,” meaning they do not result in a cancer diagnosis. False positives can also have financial implications for patients and cause significant emotional anxiety.

A major, new study led by the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center has found that women who received a false-positive result that required additional imaging or biopsy were less likely to return ...

When you ask a rideshare app to find you a car, the company’s computers get to work. They know you want to reach your destination quickly. They know you’re not the only user who needs a ride. And they know drivers want to minimize idle time by picking up someone nearby. The computer’s job, says Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Associate Professor Saket Navlakha, is to pair drivers with riders in a way that maximizes everyone’s happiness.

Computer scientists like Navlakha call this bipartite matching. It’s the same task handled by systems pairing organ donors with transplant candidates, medical students with residency ...

By Emily Greenhalgh

One of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet is closer than you think — right inside your mouth. Your mouth is a thriving ecosystem of more than 500 different species of bacteria living in distinct, structured communities called biofilms. Nearly all of these bacteria grow by splitting [or dividing] into two, with one mother cell giving rise to two daughter cells.

New research from the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) and ADA Forsyth uncovered an extraordinary mechanism of cell division in Corynebacterium matruchotii, one of the most common bacteria living in dental plaque. ...