(Press-News.org) For paleontologists who study animals that lived long ago, fossilized remains tell only part of the story of an animal’s life. While a well-preserved skeleton can provide hints at what an ancient animal ate or how it moved, irrefutable proof of these behaviors is hard to come by. But sometimes, scientists luck out with extraordinary fossils that preserve something beyond the animal’s body. Case in point: in a new study published in the journal Current Biology, researchers found fossilized seeds in the stomachs of one of the earliest birds. This discovery shows that these birds were eating fruits, despite a long-standing hypothesis that this species of bird feasted on fish (and more recent hypotheses it ate insects) with its incredibly strong teeth.

Longipteryx chaoyangensis lived 120 million years ago in what’s now northeastern China. It’s among the earliest known birds, and one of the strangest.

“Longipteryx is one of my favorite fossil birds, because it’s just so weird— it has this long skull, and teeth only at the tip of its beak,” says Jingmai O’Connor, associate curator of fossil reptiles in the Field Museum’s Neguanee Integrative Research Center and the study’s lead author.

“Tooth enamel is the hardest substance in the body, and Longipteryx’s tooth enamel is 50 microns thick. That’s the same thickness of the enamel on enormous predatory dinosaurs like Allosaurus that weighed 4,000 pounds, but Longipteryx is the size of a bluejay,” says Alex Clark, a PhD student at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago and a co-author of the paper.

Longipteryx was discovered in 2000, and at the time, scientists suggested that its kingfisher-like elongated skull meant that it too hunted fish. However, this hypothesis has been challenged by a number of scientists, including O’Connor. “There are other fossil birds, like Yanornis, that ate fish, and we know because specimens have been found with preserved stomach contents, and fish tend to preserve well. Plus, these fish-eating birds had lots of teeth, all the way along their beaks, unlike how Longipteryx only has teeth at the very tip of its beak,” says O’Connor. “It just didn’t add up.”

However, no specimens of Longipteryx had been found with fossilized food still in their stomachs for scientists to confirm what it ate— until now.

O’Connor visited the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in China, where she noticed two Longipteryx specimens that appeared to have something in their stomachs. She consulted with her colleague, paleobotanist and Field Museum associate curator of fossil plants Fabiany Herrera, who was able to determine that the tiny, round structures in the birds’ stomachs were seeds from the fruits of an ancient tree. (Or technically, flesh-covered seeds-- “true fruits” are only found in flowering plants, which were just starting to flourish 120 million years ago when Longipteryx lived. The trees that Longipteryx was feeding from were gymnosperms, relatives of today’s conifers and gingkos.)

Since Longipteryx lived in a temperate climate, it probably wasn’t eating fruits year-round; O’Connor and her colleagues suspect that it had a mixed diet which included things like insects when fruits weren’t available.

Longipteryx is part of a larger group of prehistoric birds called the enantiornithines, and this discovery marks the first time that scientists have found any stomach contents from an enantiornithine in China’s Jehol Biota despite thousands of uncovered fossils. “It’s always been weird that we didn’t know what they were eating, but this study also hints at a bigger picture problem in paleontology, that physical characteristics of a fossil don’t always tell the whole story about what animal ate or how it lived,” says O’Connor.

Since Longipteryx apparently wasn’t hunting for fish, that leaves a question: what was it using its long, pointy beak and crazy-strong teeth for? “The thick enamel is overpowered, it seems to be weaponized,” says Clark, who looked to modern birds to try to understand what Longipteryx was doing with its beak. “One of the most common parts of the skeleton that birds use for aggressive displays is the rostrum, the beak. Having a weaponized beak makes sense, because it moves the weapon further away from the rest of the body, to prevent injury.”

“There are no modern birds with teeth, but there are these really cool little hummingbirds that have keratinous projections near the tip of the rostrum that resemble what you see in Longipteryx, and they use them as weapons to fight each other,” says O’Connor. Weaponized beaks in hummingbirds have evolved at least seven times, allowing them to compete for limited resources. Clark suggested the hypothesis that perhaps Longipteryx’s teeth and beak also served as a weapon, perhaps evolving under social or sexual selection

The researchers say that beyond figuring out more about the life of one weird prehistoric bird, they hope their research helps illuminate broader questions in paleontology about how much scientists can (or can’t) trust skeletal traits to tell the story of animal behavior. “We’re trying to open up a new area of research for these early birds and get paleontologists to look at these structures, like the beak, and think about the complexity of the behaviors that these animals might have engaged in beyond just what they were eating,” says O’Connor. “There are many factors that could be shaping the structures that we see.”

This study was contributed to by Jingmai O’Connor (Field Museum), Alex Clark (Field Museum, University of Chicago), Fabiany Herrera (Field Museum), Xin Yang (Field Museum, University of Chicago), Xiaoli Wang (Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Linyi University, Shandong University of Science and Technology), Xiaoting Zheng (Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature), Han Hu (Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences), and Zhonghe Zhou (Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

###

END

In a new study published in JAMA Network Open, researchers at Thomas Jefferson University have developed a novel screening tool to measure digital health readiness, which will be critical in addressing barriers to telehealth adoption among diverse patient populations.

The COVID-19 pandemic facilitated many rapid changes in healthcare, including a shift to using telehealth services across the U.S. instead of traditional in-person doctor’s visits. This ensured that patients continued to receive vital care, while only needing access to a mobile device or computer with a webcam. But just because a ...

For more information, contact:

Nicole Fawcett, nfawcett@umich.edu

EMBARGOED for release at 11 a.m. Sept. 10, 2024

New law regulating out-of-pocket drug spending saves cancer patients more than $7,000 a year, study finds

The Inflation Reduction Act’s limit on Medicare Part D spending leads to significant savings for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — As prescription oral chemotherapies have become a common form of cancer treatment, some patients were paying more than $10,000 a year for medications. A new study ...

About The Study: In this modeling study of racial and ethnic disparities of tuberculosis (TB), these disparities were associated with substantial future health and economic outcomes of TB among U.S.-born persons without interventions beyond current efforts. Actions to eliminate disparities may reduce the excess TB burden among these persons and may contribute to accelerating TB elimination within the U.S.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Nicole A. Swartwood, MSPH, email nswartwood@hsph.harvard.edu.

To ...

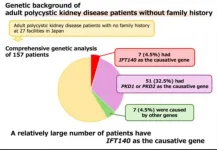

Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) researchers uncover the genetic link in patients with polycystic kidney disease lacking family history

Tokyo, Japan – Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is an intractable disorder that causes fluid-filled cysts to grow in the kidneys. It is typically seen in adults. As one of the most prevalent hereditary kidney diseases, the autosomal dominant form of PKD is usually caused by mutations in the PKD1 and PKD2 genes. However, one out of ten patients with this condition typically exhibit no family history of the disease and lack ...

NEW YORK/TORONTO – September 10, 2024 – Researchers at Klick Labs unveiled a cutting-edge, non-invasive technique that can predict chronic high blood pressure (hypertension) with a high degree of accuracy using just a person's voice. Just published in the peer-reviewed journal IEEE Access, the findings hold tremendous potential for advancing early detection of chronic high blood pressure and showcase yet another novel way to harness vocal biomarkers for better health outcomes.

The ...

WHO: The Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program (Kids First), an initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

WHAT: Kids First announces the release of three comprehensive new pediatric research datasets exploring childhood cancers and congenital disorders. New publicly available datasets include:

CHILDHOOD CANCERS

Gabriella Miller Kids First (GMKF) Pediatric Research Program in Susceptibility to Ewing Sarcoma Based on Germline Risk and Familial History of Cancer.

Principal Investigators: Joshua D. Schiffman, MD. Huntsman Cancer Institute, ...

A new study from Umeå University, Sweden, shows that the body's muscles sense mechanical pressure. This new discovery has important implications for movement neuroscience and may improve the design of training and rehabilitation to relieve stiff muscles.

"The results provide an important piece of the puzzle in understanding what information our nervous system receives from muscles," says Michael Dimitriou, associate professor at the Department of Medical and Translational Biology, ...

Women who are being treated for asthma are more likely to miscarry and need fertility treatment to get pregnant, according to a large study presented at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Congress in Vienna, Austria [1]. However, the study also suggests that most women with asthma are able to have babies.

The study was presented by Dr Anne Vejen Hansen from the department of respiratory medicine at Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark.

She said: “Asthma is common in women of reproductive age. Previous ...

ABSTRACTS: 510MO, 618MO, 1821MO, 71MO, 995MO

BARCELONA, Spain ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights provides a glimpse into recent basic, translational and clinical cancer research from MD Anderson experts. This special edition features upcoming oral presentations by MD Anderson researchers at the 2024 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress focused on clinical advances across a variety of cancer types.

In addition to the studies summarized below, forthcoming press releases will feature the following oral presentations:

Initial results from a first-in-human ...

Figshare, a leading provider of institutional repository infrastructure that supports open research, is pleased to announce that Appalachian State University has chosen Figshare as its new institutional repository platform to share, showcase and manage its research outputs.

Appalachian State University (App State) – part of the University of North Carolina System – chose Figshare as its new repository platform to replace the NC DOCKS consortial repository, which was created in 2007 and is slated to shut down at the end of 2024. The team at App State wanted to ...