(Press-News.org) Millions of birds migrate every year to escape winter, but spending time in a warmer climate does not save them energy, according to research by the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior (MPI-AB). Using miniaturized loggers implanted in wild blackbirds, scientists recorded detailed measurements of heart rate and body temperature from birds every 30 minutes from fall to the following spring—the first time the physiology of free flying birds has been quantified continuously at this scale over the entire wintering period. The data offer unprecedented insights into the true energetic costs of migrant and resident strategies and reveal a previously unknown mechanism used by migrants to save energy prior migration. The findings are published on September 18 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

“We never expected to discover that birds gain no overall energy advantage by escaping cold winters,” says Nils Linek, a first author of the study and a researcher at MPI-AB. “It was a longstanding textbook assumption that animals spend less energy by migrating to warmer places, but our findings have shown that these savings don’t add up. Rather, the energetics of migration is far more complex and interesting than theory predicted.”

Animal migration is a spectacular example of how animals adapt to changing seasons. Yet the ultimate question—why?—has remained a scientific puzzle because of the barriers to studying the physiology of free-living animals over long periods. In the new paper, researchers from MPI-AB and Yale University have unlocked an important piece of that puzzle by deploying sensors that measured the energy expenditure of blackbirds for the complete annual migration and then pairing the physiological data with modelling to calculate the predicted energetic costs of thermoregulation.

Data from the sensors showed that migrating blackbirds conserved considerable energy in preparation for migration by decreasing their metabolism three weeks before departure, potentially dwarfing the energy costs of migratory flights. “They are essentially turning down their internal thermostat, allowing them to save energy for the journey ahead,” says Linek. Yet when the migrants are in the warmer wintering areas, they do not appear to decrease total daily energy expenditure.

“This was not what we anticipated,” said Scott Yanco, co-first author on the study from the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change. “The energy modeling we did in the study predicted that migration should definitely create an energy surplus because of the substantially reduced cost of keeping warm in milder climates.”

So where did this theoretical energy surplus of migrants go? Says Linek: “We can only speculate at this point, but we suggest that there may be other physiological adaptations or hidden costs that migrant blackbirds face in their milder overwintering sites. These might include factors such as the need to maintain vigilance in new environments, immune functions or unknown stressors that offset the thermal advantage they should have experienced.”

The team worked with blackbirds in southern Germany. Like many populations throughout Europe, German blackbird populations are “partially migratory”, which means that some individuals migrate southwards to spend winter in milder regions like Spain and France, while others remain as residents on the colder breeding grounds all year. The researchers surgically implanted miniature heart rate and body temperature loggers into 120 wild birds; and the loggers recorded data every 30 minutes from September up to the following May when the devices were removed. The team also tracked the birds with radio transmitters, which signaled when the migratory individuals departed Germany in September and returned in March and April the following year. The researchers analyzed data from the loggers, totaling around 1 million data points, to compare how body temperature and heart rate differed between migrant and resident blackbirds.

“Using physiological data we were able to see with incredible detail how birds undertake and experience migration, from the migratory flight itself, to how they recovered afterwards, to what they did over winter,” says Tamara Volkmer, a co-author on the study and MPI-AB doctoral student. “By recording long-term, detailed energy measurements of migrants, we could glimpse the hidden costs of their impressive round trip.”

The study’s findings suggest that the risks and challenges of migration are not offset by energy savings in warmer climates, opening up new questions about the evolutionary drivers behind migration more broadly. “This could have implications for our understanding of migration and its underlying mechanisms across different bird species,” says Linek.

The study also has implications for predicting how species might respond to future climate scenarios, the authors say. Senior author Jesko Partecke, a group leader at MPI-AB who has been studying blackbird migration for two decades, says: “Understanding the physiological underpinnings of migration means that we can better forecast which species may adapt, which may alter their migratory patterns, and which may face greater risks as the world continues to warm.”

END

Scientists quantify energetic costs of the migratory lifestyle in a free flying songbird

Physiological measurements disprove the common theory that migration leads to overall energy savings in warmer regions

2024-09-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Understanding changes in pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease

2024-09-18

Amyloid-beta and tau proteins have long been associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The pathological buildup of these proteins leads to cognitive decline in people with the disease. How it does that, though, remains poorly understood.

A new study from the labs of Sylvain Baillet at The Neuro and Sylvia Villeneuve at the Douglas Research Centre provides important insight into how these proteins impact brain activity and possibly contribute to cognitive decline.

The team led by Jonathan Gallego Rudolf, a Ph.D. candidate in Baillet and Villeneuve’s ...

Constriction junction, do you function?

2024-09-18

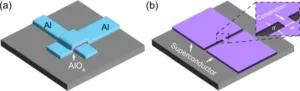

UPTON, N.Y. — Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have shown that a type of qubit whose architecture is more amenable to mass production can perform comparably to qubits currently dominating the field. With a series of mathematical analyses, the scientists have provided a roadmap for simpler qubit fabrication that enables robust and reliable manufacturing of these quantum computer building blocks.

This research was conducted as part of the Co-design Center for ...

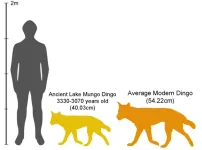

Early dingoes are related to dogs from New Guinea and East Asia

2024-09-18

New archaeological research by the University of Sydney has discovered for the first time clear links between fossils of the iconic Australian dingo, and dogs from East Asia and New Guinea.

The remarkable findings suggest that the dingo came from East Asia via Melanesia, and challenges previous claims that it derived from pariah dogs of India or Thailand.

Previous studies used traditional morphometric analysis – which looks at the size and shape of the animal using callipers – ...

$1 million grant to fund research of nerve regeneration in multiple sclerosis patients

2024-09-18

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) has awarded a grant of 1 million dollars to Dr. Isabel Pérez-Otaño, who leads the Plasticity and Remodeling of Neural Circuits laboratory at the Institute for Neurosciences (IN), a joint center of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Miguel Hernández University (UMH) of Elche. The grant is part of the NMSS 'Pathways to Cure' program that funds innovative therapeutic approaches to treat multiple sclerosis (MS). The team will work on identifying mechanisms that mediate a special kind of brain plasticity, known as myelin plasticity. The goal is to find ways to stimulate myelin plasticity ...

New tool to assess equity in scholarly communication models

2024-09-18

[Strasbourg, 18th September 2024]

A new online tool designed to assess the equity of scholarly communication models is launched today at the OASPA 2024 conference. The “How Equitable Is It” tool, developed by a multi-stakeholder Working Group, comprising librarians, library consortia representatives, funders and publishers, and convened by cOAlition S, Jisc and PLOS, aims to provide a framework for evaluating scholarly communication models and arrangements on the axis of equity.

The tool, which was inspired by the “How Open Is It?” framework, is targeted at institutions, library consortia, ...

Research shows finger counting may help improve math skills in kindergarten

2024-09-18

Preschool teachers have different views on finger counting. Some teachers consider finger counting use in children to signal that they are struggling with math, while others associate its use as advanced numerical knowledge. In a new Child Development study, researchers at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and Lea.fr, Editions Nathan in Paris, France, explored whether a finger counting strategy can help kindergarten-aged children solve arithmetic problems.

Adults rarely use their fingers to calculate a small sum (e.g., 3+2) as such behaviors could be attributed to pathological difficulties in mathematics or cognitive impairments. However, young children between ...

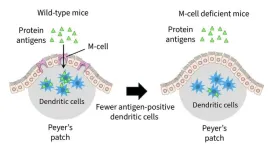

Proteins in meat, milk, and other foods suppress gut tumors

2024-09-18

Researchers led by Hiroshi Ohno at the RIKEN Center for Integrative medical sciences (IMS) in Japan have discovered that food antigens like milk proteins help keep tumors from growing in our guts, specifically the small intestines. Experiments revealed how these proteins trigger the intestinal immune system, allowing it to effectively stop the birth of new tumors. The study was published in the scientific journal Frontiers in Immunology on Sep. 18.

Food antigens get a lot of negative press because they are the source of allergic reactions to foods such as peanuts, shellfish, bread, eggs, and ...

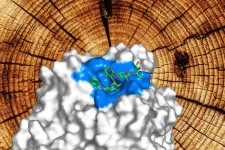

Measuring how much wood a wood shuck shucks with all-new wood shuck food

2024-09-18

Researchers want to transform the natural and abundant resource wood into useful materials, and central to that is a molecular machine found in fungi that decomposes the complex raw material into its basic components. A Kobe University researcher and his team now were the first to come up with a test feed for the fungal molecular machine that allows them to observe its close-to-natural action, opening the door to improving it and to putting it to industrial application.

Biochemical engineers want to transform the abundant and renewable material wood into bioplastics, medically relevant chemicals, food additives or fuel. ...

AACR Cancer Progress Report highlights innovative research, novel treatments, and powerful patient stories

2024-09-18

PHILADELPHIA – Today, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) released the 14th edition of its annual Cancer Progress Report. This comprehensive report provides the latest statistics on cancer incidence, mortality, and survivorship. It also outlines how basic, translational, and clinical cancer research and cancer-related population sciences—largely supported by federal investments in the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Centers for Disease ...

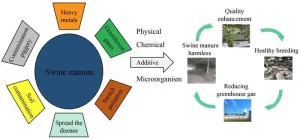

How do exogenous additives affect the direction of heavy metals and the preservation of nitrogen in pig manure compost?

2024-09-18

Most of the heavy metals in pig manure originate from feed additives, such as copper and zinc. When these heavy metals are introduced into agricultural soil, they can significantly increase the heavy metal content in crops, posing a threat to both the environment and human health. While pig manure is rich in nitrogen, an essential nutrient for crop growth, a substantial amount of nitrogen is lost in gaseous form during the composting process, impacting the quality of the compost. Moreover, this process results in the emission of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Weill Cornell Medicine selected for Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award

Largest high-precision 3D facial database built in China, enabling more lifelike digital humans

SwRI upgrades facilities to expand subsurface safety valve testing to new application

Iron deficiency blocks the growth of young pancreatic cells

Selective forest thinning in the eastern Cascades supports both snowpack and wildfire resilience

A sea of light: HETDEX astronomers reveal hidden structures in the young universe

Some young gamers may be at higher risk of mental health problems, but family and school support can help

Reduce rust by dumping your wok twice, and other kitchen tips

High-fat diet accelerates breast cancer tumor growth and invasion

Leveraging AI models, neuroscientists parse canary songs to better understand human speech

Ultraprocessed food consumption and behavioral outcomes in Canadian children

The ISSCR honors Dr. Kyle M. Loh with the 2026 Early Career Impact Award for Transformative Advances in Stem Cell Biology

The ISSCR honors Alexander Meissner with the 2026 ISSCR Momentum Award for exceptional work in developmental and stem cell epigenetics

The ISSCR honors stem cell COREdinates and CorEUstem with the 2026 ISSCR Public Service Award

Minimally invasive procedure effectively treats small kidney cancers

SwRI earns CMMC Level 2 cybersecurity certification

Doctors and nurses believe their own substance use affects patients

Life forms can planet hop on asteroid debris – and survive

Sylvia Hurtado voted AERA President-Elect; key members elected to AERA Council

Mount Sinai and King Saud University Medical City forge a three-year collaboration to advance precision medicine in familial inflammatory bowel disease

AI biases can influence people’s perception of history

Prenatal opioid exposure and well-being through adolescence

Big and small dogs both impact indoor air quality, just differently

Wearing a weighted vest to strengthen bones? Make sure you’re moving

Microbe survives the pressures of impact-induced ejection from Mars

Asteroid samples offer new insights into conditions when the solar system formed

Fecal transplants from older mice significantly improve ovarian function and fertility in younger mice

Delight for diastereomer production: A novel strategy for organic chemistry

Permafrost is key to carbon storage. That makes northern wildfires even more dangerous

Hairdressers could be a secret weapon in tackling climate change, new research finds

[Press-News.org] Scientists quantify energetic costs of the migratory lifestyle in a free flying songbirdPhysiological measurements disprove the common theory that migration leads to overall energy savings in warmer regions