(Press-News.org) Published in the journal Science, the study presents a curve of global mean surface temperature that reveals Earth's temperature has varied more than previously thought over much of the Phanerozoic Eon a period of geologic time when life diversified, populated land and endured multiple mass extinctions. The curve also confirms Earth's temperature is strongly correlated to the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The start of the Phanerozoic Eon 540 million years ago is marked by the Cambrian Explosion, a point in time when complex, hard-shelled organisms first appeared in the fossil record. Although researchers can create simulations all the way back to 540 million years ago, the temperature curve in the study focuses on the last 485 million years since there is limited geological data of temperature before then.

"It's hard to find rocks that are that old and have temperature indicators preserved in them – even at 485 million years ago we don't have that many. We were limited with how far back we could go,” said study co-author Jessica Tierney, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona.

The researchers created the temperature curve using an approach called data assimilation. This allowed them to combine data from the geologic record and climate models to create a more cohesive understanding of ancient climates.

"This method was originally developed for weather forecasting," said Emily Judd, lead author of the paper and a former postdoctoral researcher at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and the U of A. "Instead of using it to forecast future weather, here we're using it to hindcast ancient climates."

Refining scientists' understanding of how Earth's temperature has fluctuated over time provides crucial context for understanding modern climate change.

"If you're studying the last couple of million years, you won't find anything that looks like what we expect in 2100 or 2500," said Scott Wing, a co-author on the paper and a curator of paleobotany at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. "You need to go back even further to periods when the Earth was really warm, because that's the only way we're going to get a better understanding of how the climate might change in the future."

The new curve reveals that temperature varied more greatly during the past 485 million years than previously thought. Over the eon, the global temperature spanned 52 to 97 degrees Fahrenheit. Periods of extreme heat were most often linked to elevated levels of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

"This research illustrates clearly that carbon dioxide is the dominant control on global temperatures across geological time," said Tierney. "When CO2 is low, the temperature is cold; when CO2 is high, the temperature is warm."

The findings also reveal that the Earth's current global temperature of 59 degrees Fahrenheit is cooler than Earth has been over much of the Phanerozoic. But greenhouse gas emissions from human-caused climate change are currently warming the planet at a much faster rate than even the fastest warming events of the Phanerozoic, the reseaerchers say. The speed of warming puts species and ecosystems around the world at risk and is causing a rapid rise in sea level. Some other episodes of rapid climate change during the Phanerozoic have sparked mass extinctions.

Rapidly moving toward a warmer climate could spell danger for humans who have mostly lived in a 10 degree Fahrenheit range for the global temperatures, compared to the 45 degree span of temperatures over the last 485 million years, the researchers say.

"Our entire species evolved to an 'ice house' climate, which doesn't reflect most of geological history," Tierney said. "We are changing the climate into a place that is really out of context for humans. The planet has been and can be warmer – but humans and animals can't adapt that fast."

The collaboration between Tierney and researchers at the Smithsonian began in 2018. The team wanted to provide museum visitors with a curve that charted Earth's global temperature across the Phanerozoic, which began around 540 million years ago and continues into the present day.

The team collected more than 150,000 estimates of ancient temperature calculated from five different chemical indicators for temperature that are preserved in fossilized shells and other types of ancient organic matter. Their colleagues at the University of Bristol created more than 850 model simulations of what Earth's climate could have looked like at different periods of the distant past based on continental position and atmospheric composition. The researchers then combined these two lines of evidence to create the most accurate curve of how Earth's temperature has varied over the past 485 million years.

Another finding from the study pertains to climate sensitivity, a metric of how much the climate warms for the doubling of carbon dioxide.

"We found that carbon dioxide and temperature are not only really closely related, but related in the same way across 485 million years. We don't see that the climate is more sensitive when it's hot or cold," Tierney said.

In addition to Judd, Tierney, Huber and Wing, Daniel Lunt and Paul Valdes of the University of Bristol and Isabel Montañez of the University of California, Davis are coauthors on the study.

The research was supported by Roland and Debra Sauermann through the Smithsonian; the Heising-Simons Foundation and the University of Arizona's Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in Integrative Science through Tierney; and the United Kingdom’s Natural Environment Research Council.

END

Study: Over nearly half a billion years, Earth’s global temperature has changed drastically, driven by carbon dioxide

A new study co-led by the University of Arizona and the Smithsonian offers the most detailed glimpse yet into how Earth's surface temperature has changed over the past 485 million years

2024-09-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Clinical trial could move the needle in traumatic brain injury

2024-09-19

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Subscribe to UCSF News

Department of Defense-funded study aims to end a decades-long impasse in treatment development.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) results in close to 70,000 deaths in the United States every year, and it is the cause of long-term physical, cognitive and mental disability in 5 million Americans. But despite three decades of work, treatments are sorely lacking.

Now, an innovative drug development trial will be available in emergency departments of 18 level 1 trauma sites nationwide. It is launched by UC San Francisco and the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic ...

AI model can reveal the structures of crystalline materials

2024-09-19

For more than 100 years, scientists have been using X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of crystalline materials such as metals, rocks, and ceramics.

This technique works best when the crystal is intact, but in many cases, scientists have only a powdered version of the material, which contains random fragments of the crystal. This makes it more challenging to piece together the overall structure.

MIT chemists have now come up with a new generative AI model that can make it much easier to determine the structures of these powdered crystals. The prediction model could help researchers characterize ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights for September 19, 2024

2024-09-19

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Genetic factors underscore disparities in colorectal cancer survival

Patients with colorectal cancer have varied overall survival, but it remains unclear how the frequency of certain gene mutations among different racial and ethnic groups influences outcomes. To investigate, researchers led by John Paul Shen, M.D., and ...

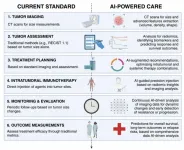

The role of artificial intelligence in advancing intratumoral immunotherapy

2024-09-19

“We explore how integrating these technologies could revolutionize personalized oncology.”

BUFFALO, NY- September 19, 2024 – A new editorial was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on September 17, 2024, entitled, “The emerging role of AI in enhancing intratumoral immunotherapy care.”

As highlighted in the abstract of this editorial, the emergence of immunotherapy (IO), and more recently, intratumoral IO, offers a novel approach to cancer treatment. This method enhances immune responses, allows for combination therapies, and helps reduce systemic adverse events. These techniques aim to ...

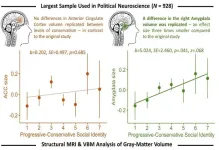

Political ideology is associated with differences in brain structure, but less than previously thought

2024-09-19

Conservative voters have slightly larger amygdalas than progressive voters—by about the size of a sesame seed. In a replication study publishing September 19 in the Cell Press journal iScience, researchers revisited the idea that progressive and conservative voters have identifiable differences in brain morphology, but with a 10x larger and more diverse sample size than the original study. Their results confirmed that the size of a person’s amygdala is associated with their political views but failed to find a consistent association between politics and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Anatomical differences in both ...

Genetic tracing at the Huanan Seafood market further supports COVID animal origins

2024-09-19

A new international collaborative study provides a list of the wildlife species present at the market from which SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, most likely arose in late 2019. The study is based on a new analysis of metatranscriptomic data released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The data come from more than 800 samples collected in and around the Huanan Seafood Wholesale market beginning on January 1, 2020, and from viral genomes reported from early COVID-19 patients. The research appears September 19 in the journal Cell.

“This is one of the most ...

Breastfeeding is crucial to shaping infant’s microbes and promoting lung health

2024-09-19

Human breast milk regulates a baby’s mix of microbes, or microbiome, during the infant’s first year of life. This in turn lowers the child’s risk of developing asthma, a new study shows.

Led by researchers at NYU Langone Health and the University of Manitoba, the study results showed that breastfeeding beyond three months supports the gradual maturation of the microbiome in the infant’s digestive system and nasal cavity, the upper part of the respiratory tract. Conversely, stopping breastfeeding earlier than three months disrupts the paced development of the microbiome and ...

Scientists at the CNIC discover an unexpected involvement of sodium transport in mitochondrial energy generation

2024-09-19

The GENOXPHOS (Functional Genetics of the Oxidative Phosphorylation System) group at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) has discovered a crucial role of sodium in the generation of cellular energy. The study, led by GENOPHOS group leader Dr. José Antonio Enríquez, also involved the participation of scientists from the Complutense University of Madrid, the Biomedical Research Institute at Hospital Doce de Octubre, the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and the Spanish research networks on frailty and healthy aging (CIBERFES) ...

Origami paper sensors could help early detection of infectious diseases in new simple, low-cost test

2024-09-19

Researchers at Cranfield University have developed an innovative new method for identifying biomarkers in wastewater using origami-paper sensors, enabling the tracking of infectious diseases using the camera in a mobile phone. The new test device is low-cost and fast and could dramatically change how public health measures are directed in any future pandemics.

Wastewater a key way to track infections

Testing wastewater is one of the primary ways to assess the prevalence of infectious diseases in populations. Researchers take samples from various ...

Safety of the seasonal influenza vaccine in 2 successive pregnancies

2024-09-19

About The Study: In this large cohort study of successive pregnancies, influenza vaccination was not associated with increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, irrespective of interpregnancy interval and vaccine type. Findings support recommendations to vaccinate pregnant people or those who might be pregnant during the influenza season.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Darios Getahun, MD, PhD, MPH, email darios.t.getahun@kp.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.34857)

Editor’s ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

New study finds deep ocean microbes already prepared to tackle climate change

ARLIS partners with industry leaders to improve safety of quantum computers

Modernization can increase differences between cultures

Cannabis intoxication disrupts many types of memory

Heat does not reduce prosociality

Advancing brain–computer interfaces for rehabilitation and assistive technologies

Detecting Alzheimer's with DNA aptamers—new tool for an easy blood test

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal study develops radiomics model to predict secondary decompressive craniectomy

New molecular switch that boosts tooth regeneration discovered

Jeonbuk National University researchers track mineral growth on bioorganic coatings in real time at nanoscale

Convergence in the Canopy: Why the Gracixalus weii treefrog sounds like a songbird

Subway systems are uncomfortably hot — and worsening

Granular activated carbon-sorbed PFAS can be used to extract lithium from brine

How AI is integrated into clinical workflow lowers medical liability perception

New biotech company to accelerate treatments for heart disease

One gene makes the difference: research team achieves breakthrough in breeding winter-hardy faba beans

Predicting brain health with a smartwatch

How boron helps to produce key proteins for new cancer therapies

Writing the catalog of plasma membrane repair proteins

A comprehensive review charts how psychiatry could finally diagnose what it actually treats

[Press-News.org] Study: Over nearly half a billion years, Earth’s global temperature has changed drastically, driven by carbon dioxideA new study co-led by the University of Arizona and the Smithsonian offers the most detailed glimpse yet into how Earth's surface temperature has changed over the past 485 million years