(Press-News.org) Link to Google Drive folder containing images:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ZTBXkIFqwl_OyIMrUA1se_iv7hqEm_52?usp=sharing

Link to release:

https://www.washington.edu/news/2024/09/25/tesla-coil-shark-intestines/

FROM: James Urton

University of Washington

206-543-2580

jurton@uw.edu

(Note: researcher contact information at the end)

For immediate release

Sept. 25, 2024

To make fluid flow in one direction down a pipe, it helps to be a shark

Flaps perform essential jobs. From pumping hearts to revving engines, flaps help fluid flow in one direction. Without them, keeping liquids going in the right direction is challenging to do.

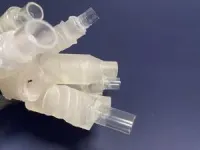

Researchers from the University of Washington have discovered a new way to help liquid flow in only one direction — but without flaps. In a paper published Sept. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they report that a flexible pipe — with an interior helical structure inspired by shark intestines — can keep fluid flowing in one direction without the flaps that engines and anatomy rely upon.

Human intestines are essentially a hollow tube. But for sharks and rays, their intestines feature a network of spirals surrounding an interior passageway. In a 2021 publication, a different team proposed that this unique structure promoted one-way flow of fluids — also known as flow asymmetry — through the digestive tracts of sharks and rays without flaps or other aids to prevent backup. That claim caught the attention of UW postdoctoral researcher Ido Levin, lead author on the new paper.

“Flow asymmetry in a pipe with no moving flaps has tremendous technological potential, but the mechanism was puzzling,” says Levin. “It was not clear which parts of the shark’s intestinal structure contributed to the asymmetry and which served only to increase the surface area for nutrient uptake.”

To answer these questions, Levin led a team that included co-authors Sarah Keller and Alshakim Nelson, both UW professors of chemistry, and Naroa Sadaba, a fellow UW postdoctoral researcher. They 3D-printed a series of “biomimetic pipes,” all with interior helices inspired by the layout of shark intestines. They varied the geometrical parameters among these prototype pipes, such as the pitch angle of the helix or the number of turns. Their first pipes were printed from rigid materials, and they found that some showed a strong preference for unidirectional flow.

“The first measurement of flow asymmetry was a ‘Eureka’ moment,” said Levin. “Until that instant, we didn’t know if our idealized structures could reproduce the flow effects seen in sharks.”

By further tuning the geometrical parameters and printing new designs, the researchers increased the flow asymmetry until it rivaled and even exceeded designs of famed inventor Nikola Tesla, who more than a century ago patented the Tesla valve, a one-way fluid flow device with no moving parts.

“You don’t get to beat Tesla every day!” said Levin.

But shark intestines — like human intestines — aren’t rigid. The team suspected that so-called “deformable structures,” which are made from more flexible materials, might perform even better as Tesla valves. They 3D-printed a second series of prototypes made from the softest polymer that is both printable and commercially available. These flexible pipe designs, which are better mimics for shark intestines through both their “deformability” and their interior helices, performed at least seven times better compared to all previously measured Tesla valves.

“Chemists were already motivated to develop polymers that are simultaneously soft, strong and printable,” said Nelson, an expert in developing new types of polymers. “The potential use of these polymers to control flow in applications ranging from engineering to medicine strengthens that motivation.”

“Actual intestines are still about 100 times softer than our soft material, so there is plenty of room for improvement,” said Sadaba.

Keller credits the project’s success to the team’s interdisciplinary ideas from biology, chemistry and physics, and to the sharks themselves.

“Biomimicry is a powerful way of discovering new designs,” said Keller. “We never would have thought of the structures ourselves.”

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Washington Research Foundation and the Fulbright Foundation.

###

For more information, contact Keller at slkeller@uw.edu, Nelson at alshakim@uw.edu and Levin at idolevin@uw.edu.

Grant numbers: MCB-1925731, MCB-2325819, EFMA-2223537

END

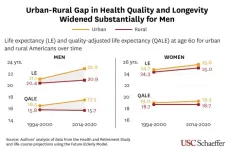

Rural men are dying earlier than their urban counterparts, and they’re spending fewer of their later years in good health, according to new research from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

Higher rates of smoking, obesity and cardiovascular conditions among rural men are helping fuel a rural-urban divide in illness, and this gap has grown over time, according to the study published this week in the Journal of Rural Health. The findings suggest that by the time rural men reach age 60, there are limited opportunities to fully address this disparity, and earlier interventions may be needed to prevent it from widening ...

Held annually, NY Climate Week is a pivotal event in the global climate change calendar. Bringing together notable leaders, celebrities, climate professionals, and innovators from around the world, the event serves as a critical platform for discussing and advancing climate action. This year’s theme, "It’s Time," underscores the urgency for immediate and ambitious efforts to tackle climate change, and the process could be accelerated with Generative AI and other cutting-edge technologies.

Insilico Medicine ...

Young adults who vape show chemical changes in their DNA similar to those found in young adults who smoke — changes known to be linked to the development of cancer — according to a new study just published in the American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology.

A team of researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC measured DNA methylation, a chemical modification of DNA that can effectively turn genes “on” or “off, in the oral cells of young adult vapers, smokers and non-users. DNA methylation is vital to normal cellular ...

DALLAS, Sept. 25, 2024 — The American Heart Association, celebrating 100 years of lifesaving service as the world’s leading nonprofit organization focused on heart and brain health for all, is joining with other top cardiovascular research funders around the world to support an international scientific research grant focused on women’s cardiovascular health. Scientific researchers around the world are invited to apply for the award to foster global advancements in understanding and improving the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among women.

A 2022 presidential advisory ...

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), recently reclassified as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), has become the most prevalent chronic liver disease globally. This reclassification underscores the metabolic dysfunction central to the disease, which spans a spectrum from simple steatosis to more severe forms like steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Given the significant overlap between MASLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the therapeutic strategies for MASLD have increasingly focused on addressing metabolic derangements. Despite its global prevalence, no specific drugs have been approved for MASLD, highlighting an urgent need ...

September 25, 2024 (Washington, DC)—The Kissick Family Foundation Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) Grant Program, in partnership with the Milken Institute Science Philanthropy Accelerator for Research and Collaboration (SPARC), today announced six research teams awarded two-year grants to advance scientific understanding of FTD, totaling $3 million in new funding for this disease.

This inaugural cycle of the Kissick Family Foundation FTD Grant Program represents a unique philanthropic strategy that specifically targets basic or early-stage translational research projects that focus on those disease cases ...

Metastatic cancer can be a devastating diagnosis. The cancer is spreading. It may travel to multiple organs in the body. This could mean more pain and ultimately, death.

Unfortunately, just how cancer spreads remains unclear. But now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Adam Siepel and colleagues have a way to better understand that process. New technology developed at Weill Cornell Medicine barcodes cells to track the highways by which prostate cancer spreads throughout the body.

The resulting roadmap shows that most cancer cells actually stay put within the tumor. However, ...

Augmented reality (AR) takes digital images and superimposes them onto real-world views. But AR is more than a new way to play video games; it could transform surgery and self-driving cars. To make the technology easier to integrate into common personal devices, researchers report in ACS Photonics how to combine two optical technologies into a single, high-resolution AR display. In an eyeglasses prototype, the researchers enhanced image quality with a computer algorithm that removed distortions.

AR systems, like those in bulky goggles and automobile head-up displays, require portable optical components. But shrinking the typical four-lens AR system to the size of eyeglasses or smaller ...

Professor Ron Boschma is the first Dutch person to receive the Prix Vautrin Lud, the highest academic award within the field of geography. The award will be presented in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, France on 6 October. Prior to the award ceremony, Prof. Boschma will give an invited lecture at the Sorbonne University in Paris on 4 October. Boschma was nominated for the award in recognition of his scientific contributions to the field of economic geography, especially for laying the foundations of evolutionary economic geography and his research into regional diversification and innovation policy. The European Union’s regional policy is based in part on his ...

Research Highlights Risk to Both Humans and Wildlife, Suggests Need for New Collision Mitigation Strategies

A recent article published in PeerJ Life & Environment has uncovered insights into how mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) respond to approaching vehicles, revealing that these common waterbirds are poorly equipped to avoid collisions, particularly at high speeds. The research, which used both simulated and real-world vehicle approaches, highlights the urgent need for improved methods to reduce bird-vehicle collisions—events that are not only financially costly but also dangerous to both humans and wildlife.

The study focused ...