(Press-News.org) Sea robins are ocean fish particularly suited to their bottom-dwelling lifestyle: Six leg-like appendages make them so adept at scurrying, digging, and finding prey that other fish tend to hang out with them and pilfer their spoils.

A chance encounter in 2019 with these strange, legged fish at Cape Cod’s Marine Biological Laboratory was enough to inspire Corey Allard to want to study them.

“We saw they had some sea robins in a tank, and they showed them to us, because they know we like weird animals,” said Allard, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Nicholas Bellono, professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. The Bellono lab investigates sensory biology and cellular physiology of many marine animals, including octopuses, jellyfish, and sea slugs.

“Sea robins are an example of a species with a very unusual, very novel trait,” Allard continued. “We wanted to use them as a model to ask, ‘How do you make a new organ?’”

Allard’s ensuing deep dive into sea robin biology led to a collaboration with Stanford researchers studying the fish’s developmental genetics and culminated in back-to-back papers in Current Biology, co-authored by Bellono and Amy Herbert and David Kingsley at Stanford University, and others. The studies provide the most comprehensive understanding to date on how sea robins use their legs, what genes control the emergence of those legs, and how these animals could be used as a conceptual framework for evolutionary adaptations.

Sea robin “legs” are actually extensions of their pectoral fins, of which they have three on each side. Allard first sought to determine whether the legs are bona fide sensory organs, which scientists had suspected but never confirmed. He ran experiments observing captive sea robins hunting prey, in which they alternate between short bouts of swimming and “walking.” They also occasionally scratch at the sand surface to find buried prey, like mussels and other shellfish, without visual cues. The researchers realized that the legs were sensitive to both mechanical and chemical stimuli. They even buried capsules containing only single chemicals, and the fish could easily find them.

Serendipity led to another chance discovery. They received a fresh shipment of fish mid-study that looked like the originals, but the new fish, Allard said, did not dig and find buried prey or capsules like the originals could. “I thought they were just some duds, or maybe the setup didn’t work,” Bellono recalled, laughing.

It turned out the researchers had acquired a different species of sea robin. In their studies, they ended up characterizing them both – Prionotus carolinus, which dig to find buried prey and are highly sensitive to touch and chemical signals, and P. evolans, which lack these sensory capabilities and use their legs for locomotion and probing, but not for digging.

Examining the leg differences between the two fish, they found that the digging variety’s were shovel-shaped and covered in protrusions called papillae, similar to our taste buds. The non-digging fish’s legs were rod-shaped and lacked papillae. Based on these differences, the researchers concluded that papillae are evolutionary sub-specializations.

Allard’s paper describing the evolution of sea robins’ novel sensory organs included analysis of sea robin specimens from the Museum of Comparative Zoology to examine leg morphologies across species and time. The digging species are restricted to only a few locations, he found, suggesting a relatively recent evolution of this trait.

Studying sea robin legs wasn’t just about hanging out with weird animals (although that was fun too). The walking fish are a potentially powerful model organism to compare specialized traits, and to teach us about how evolution allows for adaptation to very specific environments.

About 6 million years ago, humans evolved the ability to walk upright, separating from their primate ancestors. Bipedalism is a defining feature of our species, and we only know so much about how, when, and why that change occurred. Sea robins and their adaptation to living on the ocean floor could offer clues. For example, there are genetic transcription factors that control the development of the sea robins’ legs that are also found in the limbs of other animals, including humans.

The second study that was focused on genetics included the Kingsley lab at Stanford; Italian physicist Agnese Seminara; and biologist Maude Baldwin from the Max Planck Institute in Germany; and comprehensively examined the genetic underpinnings of the walking fish’s unusual trait. The researchers used techniques including transcriptomic and genomic editing to identify which gene transcription factors are used in leg formation and function in the sea robins. They also generated hybrids between two sea robin species with distinct leg shapes to explore the genetic basis for these differences.

“Amy and Corey did a lot to describe this animal, and I think it’s pretty rare to go from the description of the behavior, to the description of the molecules, to the description of an evolutionary hypothesis,” Bellono said. “I think this is a nice blueprint for how one poses a scientific question and rigorous follows it with a curious and open mind.”

END

This fish has legs

Sea robins as evolutionary model for trait development

2024-09-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Climate change: Heat, drought, and fire risk increasing in South America

2024-09-26

The number of days per year that are simultaneously extremely hot, dry, and have a high fire risk have as much as tripled since 1970 in some parts of South America. The results are published in a study in Communications Earth & Environment.

South America is warming at a similar rate to the global average. However, some regions of the subcontinent are more at risk of the co-occurrence of multiple climate extremes. These compound extremes can have amplified impacts on ecosystems, economy, and human health.

Raúl Cordero and colleagues calculated the number of days per year that each approximately 30 by 30 km grid ...

Rates of sudden unexpected infant death before and during the pandemic

2024-09-26

About The Study: This cross-sectional study found increased rates of both sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a significant shift in epidemiology from the pre-pandemic period noted in June to December 2021. These findings support the hypothesis that off-season resurgences in endemic infectious pathogens may be associated with SUID rates, with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) rates in the U.S. closely approximating this shift. Further investigation into the role ...

Estimation of tax benefit of nonprofit hospitals

2024-09-26

About The Study: This study highlights the wide variation of nonprofit hospitals’ tax benefit across states, its high concentration among a small number of hospitals, and the primary role played by state and local taxes. Policy efforts to strengthen nonprofit hospitals’ taxpayer accountability are likely to be more effective when pursued at the local level.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Ge Bai, PhD, CPA, email gbai@jhu.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media ...

Scientists discover gene responsible for rare, inherited eye disease

2024-09-26

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and their colleagues have identified a gene responsible for some inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), which are a group of disorders that damage the eye’s light-sensing retina and threatens vision. Though IRDs affect more than 2 million people worldwide, each individual disease is rare, complicating efforts to identify enough people to study and conduct clinical trials to develop treatment. The study’s findings published today in JAMA Ophthalmology.

In a small study of six unrelated participants, researchers linked the gene UBAP1L to different forms of ...

Scientists discover "pause button" in human development

2024-09-26

In some mammals, the timing of the normally continuous embryonic development can be altered to improve the chances of survival for both the embryo and the mother. This mechanism to temporarily slow development, called embryonic diapause, often happens at the blastocyst stage, just before the embryo implants in the uterus. During diapause, the embryo remains free-floating and pregnancy is extended. This dormant state can be maintained for weeks or months before development is resumed, when conditions are favorable. Although not all mammals use this reproductive ...

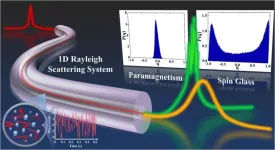

Replica symmetry breaking in 1D Rayleigh scattering system: Theory and validations

2024-09-26

In both the natural world and human society, there commonly exist complex systems such as climate systems, ecological systems, and network systems. Due to the involvement of numerous interacting elements, complex systems can stay in multiple different states, and their overall behavior generally exhibits randomness and high disorder. For example, due to the complex interactions between factors such as solar radiation, terrain, and ocean currents, the climate system can exhibit various states like sunny, cloudy, and rainy. The dynamic changes and mutual influences of these factors make the behavior of the climate highly uncertain and difficult to predict accurately. For instance, the formation ...

New research identifies strong link between childhood opportunities and educational attainment and earnings as a young adult

2024-09-26

Washington, September 26, 2024—The number of educational opportunities that children accrue at home, in early education and care, at school, in afterschool programs, and in their communities as they grow up are strongly linked to their educational attainment and earnings in early adulthood, according to new research. The results indicate that the large opportunity gaps between low- and high-income households from birth through the end of high school largely explain differences in educational and income achievement ...

Statement by NIH on research misconduct findings

2024-09-26

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE

Thursday, September 26, 2024 - 9 a.m. EDT

Contact:

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

NIH News Media Branch

301-496-5787

Statement by NIH on Research Misconduct Findings

Following an investigation, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has made findings of research misconduct against Eliezer Masliah, M.D., due to falsification and/or fabrication involving re-use and relabel of figure panels representing different experimental results in two publications. NIH will notify the two journals of its findings so that appropriate action can be taken. NIH initiated its research misconduct review process ...

Pregnant women who sleep less than 7 hours a night may have children with developmental delays

2024-09-26

WASHINGTON—Pregnant women who do not get enough sleep may be at higher risk of having children with neurodevelopmental delays, according to new research published in the Endocrine Society’s Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Short sleep duration (SSD) is defined as sleeping less than seven hours per night. Pregnant woman may have trouble sleeping due to hormonal changes, pregnancy discomfort, frequent urination, and other factors.

It’s been reported that almost 40% of pregnant women have SSD. These women may have ...

ESO telescope captures the most detailed infrared map ever of our Milky Way

2024-09-26

Astronomers have published a gigantic infrared map of the Milky Way containing more than 1.5 billion objects ― the most detailed one ever made. Using the European Southern Observatory’s VISTA telescope, the team monitored the central regions of our Galaxy over more than 13 years. At 500 terabytes of data, this is the largest observational project ever carried out with an ESO telescope.

“We made so many discoveries, we have changed the view of our Galaxy forever,” says Dante Minniti, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

[Press-News.org] This fish has legsSea robins as evolutionary model for trait development