(Press-News.org) CNIO researchers have discovered that cancer perverts certain brain cells, the astrocytes, and causes them to produce a protein that works in favour of the tumour.

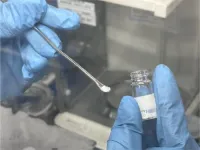

A drug, silibinin, inhibits this protein, and could be used to help treat brain metastasis with immunotherapy. A clinical trial is underway.

The work is published in the American Association for Cancer Research's journal Cancer Discovery.

Researchers at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) propose a new treatment for brain metastases that respond poorly, or not at all, to immunotherapy, and provide a biomarker to predict in which cases it should be used.

Our bodies have a mechanism to destroy anything that attacks it, be it viruses, bacteria or cancer cells: the immune system. Cancer grows when tumour cells fool this system into not attacking them. Cancer immunotherapy uses drugs to prevent cancer cells from blocking the immune system, but immunotherapy doesn’t always work.

For brain metastasis—when a tumour that started in another organ spreads to the brain—immunotherapy has recently been tried, with mixed results.

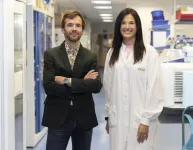

"Brain metastasis poses a serious clinical problem," explains Manuel Valiente, head of the CNIO Brain Metastasis Group and director of the study whose results are now being published. "Patients with advanced brain metastases, that is, those who can already perceive symptoms of metastases, don’t respond well to immunotherapy. But even patients who respond well to immunotherapy increasingly relapse, often because of new metastases in the brain."

In other words, immunotherapy combined with blocking antibodies doesn’t seem to be the optimal way to fight brain metastasis. One possible reason is the presence of the blood-brain barrier, a kind of permeable membrane that filters blood entering the brain to protect it from toxins. But this vascular barrier also hinders the entry of antibodies used in immunotherapy. Without antibodies, immunotherapy doesn’t work.

Astrocytes that ally with cancer

The CNIO group now proposes a very innovative hypothesis to combat this problem. They present it in the journal Cancer Discovery, published by the American Association for Cancer Research.

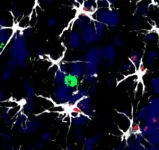

We have discovered," explains Neibla Priego, first author of the paper, "that certain brain cells called astrocytes act as immunomodulators, that is, they interact with the immune system in the brain, and in cases of brain metastasis they misuse this function because they are being influenced by the tumour."

Perverted in this way by cancer, astrocytes ally with tumour cells when brain metastasis occurs. The interaction of astrocytes with the immune system, which should be a normal process of immunomodulation, becomes a mechanism that fuels cancer, because astrocytes interfere with the work of defence cells and prevent them from killing tumour cells.

A biomarker of metastasis where immunotherapy won’t work

The CNIO group has identified a key molecule in the process, called TIMP1. "Pro-tumour astrocytes produce TIMP1, and this protein is involved in disabling the defensive cells that should kill cancer cells," says Priego.

Having demonstrated that this molecule, TIMP1, acts on immune system cells and renders them less effective, the CNIO team proposes to use it as a biomarker to detect brain metastases affected by this immunosuppressive mechanism.

"TIMP1 is a good biomarker, because it is secreted in significantly higher amounts in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with brain metastases," says Priego.

Drug targeting pro-tumour astrocytes in trials

The study goes further. Manuel Valiente's group proposes a therapeutic alternative that targets astrocytes: the combination of immunotherapy with inhibitors that prevent the production of the TIMP1 molecule.

"There is a drug called silibinin, which has already been employed on a compassionate use basis, which inhibits the production of the TIMP1 molecule," says Valiente. "A clinical trial is already underway to test its therapeutic efficacy in brain metastasis. We hope to have the results in 2025."

The goal is to combine TIMP1 inhibition with traditional immunotherapy, "which would increase the potency of the therapeutic strategy and facilitate its incorporation into clinical protocols," says Valiente.

Advances in basic knowledge

The researcher also highlights the other value of the work: to reveal the role of astrocytes in the disease, "unmasking their heterogeneity and targeting only those subtypes of astrocytes with an altered and negative function for the patient."

"Until now, astrocytes have not been considered as immunomodulators, either in general studies or in relation to brain tumours. Our research is not only innovative from a clinical point of view, but also very useful for the advancement of scientific knowledge," says Valiente.

This work has received funding from several national institutions, such as the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC), the Spanish Ministry for Economy, Trade and Enterprises (MINECO), the Carlos III Institute of Health, ‘la Caixa’ Foundation, Ramón Areces Foundation or La Marató de TV3 Foundation. It has further been funded by international entities such as the European Research Council (ERC), the European Union via Next Generation Funds, or the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO).

END

CNIO researchers propose a new treatment for brain metastasis based on immunotherapy

2024-10-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Discovery of promising electrolyte for all-solid-state batteries

2024-10-02

Often overlooked, rechargeable batteries play an important part in contemporary life, powering small devices like smartphones to larger ones like electric vehicles. The keys to creating sustainable rechargeable batteries include having them hold their charge longer, giving them a longer life with more charging cycles, and making them safer. Which is why there is so much promise in all-solid-state batteries.

The problem so far is discovering which solid electrolytes offer such potential advantages.

In a step toward that goal, an Osaka Metropolitan University research group led by Assistant Professor Kota Motohashi, Associate Professor Atsushi Sakuda, ...

One-minute phone breaks could help keep students more focused in class and better in tests

2024-10-02

Phones can be useful tools in classrooms to remind students of deadlines or encourage more exchange between students and teachers. At the same time, they can be distracting: Students report using their phones for non-academic purposes as often as 10 times a day. Thus, in many classrooms, phones are not allowed.

Now, researchers in the US have investigated if letting students use their phones for very brief amounts of time – dubbed phone or technology breaks – can enhance classroom performance and reduce phone use.

“We show that technology breaks may be helpful for reducing cell phone use in the college classroom,” said Prof Ryan Redner, a ...

New study identifies gaps in menopause care in primary care settings

2024-10-02

CLEVELAND, Ohio (Oct 2, 2024)—Timely identification and treatment of bothersome hot flashes have the potential to improve the lives of many women and save employers countless days of related absenteeism and lost work productivity. Yet, a new study finds that such symptoms are often not documented in electronic health records (EHRs) or not adequately addressed during primary care visits. The study is published online today in Menopause, the journal of The Menopause Society.

Approximately 75% of women experience hot flashes as they go through the menopause transition. Despite the common occurrence of these bothersome ...

Do coyotes have puppy dog eyes? New study reveals wild canines share dog's famous expression

2024-10-02

New research from Baylor University reveals that coyotes, like domestic dogs, have the ability to produce the famous "puppy dog eyes" expression. The study – "Coyotes can do 'puppy dog eyes' too: Comparing interspecific variation in Canis facial expression muscles," published in the Royal Society Open Science – challenges the hypothesis that this facial feature evolved exclusively in dogs as a result of domestication.

The research team, led by Patrick Cunningham, a Ph.D. research student in the Department ...

Scientists use tiny ‘backpacks’ on turtle hatchlings to observe their movements

2024-10-02

New research suggests that green turtle hatchlings ‘swim' to the surface of the sand, rather than ‘dig’, in the period between hatching and emergence. The findings have important implications for conserving a declining turtle population globally.

Published today in Proceedings B, scientists from UNSW’s School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, used a small device, known as an accelerometer, to uncover novel findings into the behaviours of hatchlings as they emerge from their nests.

Sea turtle eggs are buried in nests 30 – 80cm deep. Once hatched, the newborn turtles make their way to the surface ...

Snakes in the city: Ten years of wildlife rescues reveal insights into human-reptile interactions

2024-10-02

A new analysis of a decade-long collection of wildlife rescue records in NSW has delivered new insights into how humans and reptiles interact in urban environments.

Researchers from Macquarie University worked with scientists from Charles Darwin University, and the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water to analyse over 37,000 records of snake and lizard rescues in the Greater Sydney region between 2011 and 2021.

Their study, Interactions between reptiles and people: a perspective from wildlife rehabilitation records is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science on Wednesday 2 October.

Lead author Teagan Pyne, ...

Costs of fatal falls among US older adults trump those attributed to firearm deaths

2024-10-01

The cost of fatal falls among older people (45-85+) trump those of firearm deaths in the US, finds research published in the open access journal Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open.

The stark economics and shifting age demographics in the US underscore the urgency of preventive measures, conclude the researchers.

Falls account for around 1 in 5 of all injury-related hospital admissions, and the World Health Organization reports that falls are the second leading cause of unintentional injury deaths worldwide, with the over 65s especially vulnerable, highlight the researchers.

Like falls, firearms related injuries ...

Harmful diagnostic errors may occur in 1 in every 14 general medical hospital patients

2024-10-01

Harmful diagnostic errors may be occurring in as many as 1 in every 14 (7%) hospital patients—at least those receiving general medical care—suggest the findings of a single centre study in the US, published online in the journal BMJ Quality & Safety.

Most (85%) of these errors are likely preventable and underscore the need for new approaches to improving surveillance to avoid these mistakes from happening in the first place, say the researchers.

Previously published reports suggest that current trigger tools for ...

Closer look at New Jersey earthquake rupture could explain shaking reports

2024-10-01

The magnitude 4.8 Tewksbury earthquake surprised millions of people on the U.S. East Coast who felt the shaking from this largest instrumentally recorded earthquake in New Jersey since 1900.

But researchers noted something else unusual about the earthquake: why did so many people 40 miles away in New York City report strong shaking, while damage near the earthquake’s epicenter appeared minimal?

In a paper published in The Seismic Record, YoungHee Kim of Seoul National University and colleagues show how the earthquake’s ...

Researchers illuminate inner workings of new-age soft semiconductors

2024-10-01

One of the more promising classes of materials for next-generation batteries and electronic devices are the organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors, OMIECs for short. These soft, flexible polymer semiconductors have promising electrochemical qualities, but little is known about their molecular microstructure and how electrons move through them – an important knowledge gap that will need to be addressed to bring OMIECs to market.

To fill that void, materials scientists at Stanford recently employed ...