(Press-News.org) Utilizing one of the longest-running ecosystem experiments in the Arctic, a Colorado State University-led team of researchers have developed a better understanding of the interplay among plants, microbes and soil nutrients — findings that offer new insight into how critical carbon deposits may be released from thawing Arctic permafrost.

Estimates suggest that Arctic soils contain nearly twice the amount of carbon that is currently in the atmosphere. As climate change has caused portions of Earth’s northernmost polar regions to thaw, scientists have long been concerned about significant amounts of carbon being released in the form of greenhouse gases, a process fueled by microbes.

Much of the efforts to study and model this scenario have focused specifically on how rising global temperatures will disrupt the carbon currently locked in Arctic soils. But warming is impacting the region in other ways, too, including changing plant productivity, the overall composition of vegetation across the landscape, and the balance of nutrients in the soil. These changes in plant composition will also affect the way carbon is cycled from the soil into the atmosphere, according to a study published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change. The work was led by Megan Machmuller, a research scientist in CSU’s Soil and Crop Sciences Department.

“Our work focused on pinpointing the mechanisms that are responsible for controlling the fate of carbon in the Arctic,” Machmuller said. “We know temperature plays a large role, but there are also ecosystem shifts that are co-occurring with climate change in this region.”

In particular, Machmuller said, the region is experiencing a kind of “shrub-ification” — an increase in shrub abundance and growth. And what Machmuller and her co-authors found is that over long periods those shrubs may contribute to keeping more carbon in the ground.

“There’s been a lot of focus on the direct effects of warming on soil carbon,” said co-author Laurel Lynch, assistant professor at the University of Idaho, “but what we’re finding with this work is that it’s more complex. We need to think about this ecosystem as a whole community with many interacting parts and competing mechanisms.”

A surprising finding

For the new work, Machmuller and team tested soil samples from a 35-year ecosystem experiment in the Arctic. In 1981, scientists began adding nutrients to test plots at the Arctic Long-Term Ecological Research site in northern Alaska, situated near Toolik Lake at the base of the Brooks Mountain Range. The original idea was to understand how Arctic vegetation would respond to additional nutrients over time, but the experiment has also allowed scientists to examine how long-term changes to the soil can impact carbon storage.

After 20 years, scientists found that there had been a significant loss of soil carbon when nutrients were added compared to the control plots, an important finding that shaped broad scientific understanding of how the Arctic might respond to climate change. Those experiments continued, and Machmuller and her team tested the plots again after 35 years of continuous nutrient application.

Instead of continued carbon loss, however, they found that the trend had reversed. After 35 years, the amount of carbon stored in the test plots had either recovered or exceeded the amount in the nearby control plots. “We were really surprised by these results and became curious about the underlying mechanism,” Machmuller said.

Machmuller and her team ran advanced isotope tracing experiments in the lab to learn more about how carbon was moving through the system. What they found was that when the nutrients were first added, they stimulated microbial decomposition — a natural process that involves microbes churning through organic matter in the soil that results in the release of carbon dioxide.

But that changed over time, as nutrients were continuously added to the test plots. “Shrubs conditioned the soil in a way that shifted microbial metabolism, slowing rates of decomposition and allowing soil carbon stocks to rebuild,” Lynch said. “We didn’t expect that.”

“This offers a potential biological mechanism that might explain why we observed a net loss of carbon in the first 20 years but not after 35,” Machmuller said.

The importance of looking long-term

These results, Machmuller said, demonstrate that how the Arctic might respond to climate change is more complicated than previously thought. “It’s a complex puzzle,” she said, “and this study has emphasized for us the importance of using long-term studies to advance our understanding of ecosystem processes.”

Gus Shaver, a researcher scientist who helped set up the initial Toolik Lake experimental plots in 1981 and is a co-author on the study, also stressed the value of doing this kind of work over longer periods of time. “We’ve shown that long-term experiments offer frequent surprises as we follow the trajectory of their responses over time,” Shaver said. “What you find in the first few years of an experiment is often not what you learn from the 10th or 15th or 35th year.”

Lynch noted that as this ecosystem changes, there are other factors to consider beyond just carbon. Although an increase in shrub abundance could keep more soil carbon from transferring into the atmosphere, other impacts are not as beneficial, she said. “When you have one plant species that is massively outcompeting the rest of the community, there are major ecosystem implications,” Lynch said. For example, she said, “habitat and food sources for many animals in the Arctic depend on diverse plant communities, and the loss of this diversity can ripple through the entire ecosystem.”

Lauren Gifford, associate director of CSU’s Soil Carbon Solutions Center, who was not involved with the study, said the work highlights the need for more robust and detailed modeling to better anticipate how climate change will impact the carbon stored in the Arctic. “This is a remarkable 35-year study of one of Earth’s most vulnerable ecosystems,” Gifford said. “Even with comprehensive long-term studies, the impacts of climate change often remain uncertain. Interventions to help adapt to and mitigate climate change may lead to outcomes that are analogous, contradictory, or produce unintended consequences.”

For her part, Machmuller hopes the work will encourage future research on this topic. “Carbon research in the Arctic has been a hot topic for a long time because of the critical role it plays in regulating our global climate,” she said. “But we still don’t have a handle on what exactly the future carbon balance will look like.”

END

Decades-long research reveals new understanding of how climate change may impact caches of Arctic soil carbon

2024-10-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How Soviet legacy has influenced foreign policy in Georgia and Ukraine

2024-10-03

The legacy of the Soviet Union’s collapse plays a greater role in the foreign policies of Georgia and Ukraine than previous studies have suggested. Conducting foreign policy in former Soviet countries can be a major challenge as the Russian state does not accept the new order. These are the findings outlined in the thesis of political scientist Per Ekman from Uppsala University.

“To understand Russia’s war in Ukraine, for example, it is important to see the war as part of a longer historical event. Since their first day of independence, Georgia and Ukraine have had to deal with Russian ambitions to control the region. For many in the West, it took a ...

Robin Dunbar: Pioneering evolutionary psychologist redefines human social networks

2024-10-03

Oxford, UK – Genomic Press has released a captivating interview with Professor Robin Dunbar, the eminent evolutionary psychologist and anthropologist whose work has fundamentally altered our understanding of human social networks. Published in the Innovators and Ideas section of Genomic Psychiatry, this in-depth conversation offers unique insights into Professor Dunbar's scientific journey and the far-reaching implications of his research.

Professor Dunbar, best known for conceptualizing "Dunbar's number" - the cognitive limit to the number of stable social relationships ...

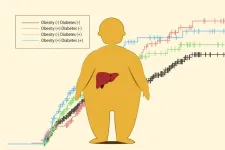

Balancing health: diabetes and obesity increase risk of liver cancer relapse

2024-10-03

Hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer associated with hepatitis infections, is known to have a high recurrence rate after cancer removal. Recent advances in antiviral therapy have reduced the number of patients affected, but obesity and diabetes are factors in hepatocellular carcinoma prevalence. However, these factors’ effects on patient survival and cancer recurrence have been unclear.

To gain insights, Dr. Hiroji Shinkawa’s research team at Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Medicine analyzed the relationship between diabetes mellitus, obesity, and postoperative outcomes in 1,644 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma ...

Duke-NUS launches new pictograms to clarify medication instructions, enhancing patient care

2024-10-03

Duke-NUS introduces 35 innovative pictograms to make medication instructions clearer, especially for seniors.

These visual aids are designed to ensure patients take their medications correctly and safely, with the aim of improving overall health outcomes.

The team looks to collaborate with healthcare institutions and pharmacies to standardise pictograms portraying medication instructions across Singapore.

SINGAPORE, 3 OCTOBER 2024 – Transforming patient care through clarity and simplicity, Duke-NUS Medical School has introduced visual aids or pictograms designed to make medication instructions clearer. ...

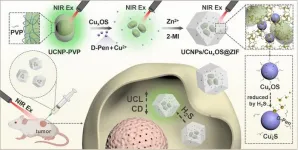

Chiral nanocomposite for highly selective dual-mode sensing and bioimaging of hydrogen sulfide

2024-10-03

With the continuous development of nanotechnology, more artificial chiral nanomaterials have been constructed. As one of the most representative optical properties of these chiral nanomaterials, CD is a powerful sensing technology. Compared with other analytical methods, CD signal has higher sensitivity, but it cannot achieve in-situ imaging in vivo. Scientists have managed to prepare chiral nanocomposites with more diverse biological functional properties to compensate for this shortcoming. However, some chiral nanocomposites assembled by electrostatic adsorption or other methods are easily dissociated and destroyed in complex physiological environments, resulting in performance ...

UCLA researchers develop new risk scoring system to account for role of chronic illness in post-surgery mortality

2024-10-03

FINDINGS

A UCLA research team has created the Comorbid Operative Risk Evaluation (CORE) score to better account for the role chronic illness plays in patient's risk of mortality after operation, allowing surgeons to adjust to patients’ pre-existing conditions and more easily determine mortality risk.

BACKGROUND

For almost 40 years, researchers have used two tools, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI), to measure the impact of existing health conditions on patient outcomes. These tools use ICD codes that are input by medical professionals and billers to account for patient illness. These ...

Mount Sinai BioDesign expands industry collaborations to expedite and enhance the development of innovative surgical technologies

2024-10-02

Mount Sinai Health System today announced that Mount Sinai BioDesign, the medical technology incubator of the Health System, has expanded its reach to become a key, effective partner for the broader MedTech community.

Through synergistic partnerships between clinicians, technologists, and industry partners, Mount Sinai BioDesign is able to offer an array of services, including expert clinical and engineering feedback, preclinical trial development and execution, data gathering and analysis, and pivotal clinical study management. Mount Sinai BioDesign has already established several mature partnerships that have ...

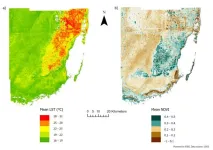

Study reveals limits of using land surface temperature to explain heat hazards in Miami-Dade County

2024-10-02

Study Reveals Limits of Using Land Surface Temperature to Explain Heat Hazards in Miami-Dade County

The findings underscore the importance of further research to enhance our understanding of urban heat dynamics in subtropical and tropical regions, ensuring that heat mitigation efforts are informed by the most accurate data available.

A recent study published in the journal PLOS Climate on October 2, 2024, examines the effectiveness of using land surface temperatures (LSTs) as proxies for ...

The Lancet Public Health: Accelerating actions to eliminate tobacco smoking could help increase life expectancy and prevent millions of premature deaths by 2050, modelling study suggests

2024-10-02

First in-depth forecasts of future worldwide health impacts of smoking reveal potential effects of eliminating smoking on life expectancy and premature deaths by 2050.

Based on current trends, global smoking rates could continue to decrease to 21.1% in males and 4.18% in females by 2050.

Analysis indicates accelerating actions towards the elimination of smoking globally would increase life expectancy and prevent millions of premature deaths, resulting in 876 million fewer years of life lost (YLLs).

Reducing smoking rates to 5% by 2050 would increase life expectancy by one year among males and 0.2 years among females ...

The Lancet Public Health: Banning tobacco sales among young people could prevent 1.2 million lung cancer deaths, global modelling study suggests

2024-10-02

Analysis of the impact on lung cancer deaths of banning tobacco sales in people born between 2006 and 2010 indicates 1.2 million deaths could be avoided.

The findings suggest the creation of a tobacco-free generation could prevent almost half (45.8%) of future lung cancer deaths in men, and around one-third (30.9%) in women, in this birth cohort.

Nearly two-thirds (65.1%) of the deaths averted would be in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Close to two-thirds (61.1%) of all lung cancer deaths in high-income countries would be avoided.

Creating a generation of people who never smoke could prevent 1.2 million deaths from lung cancer globally, according ...