(Press-News.org) Every second, more than 3,000 stars are born in the visible universe. Many are surrounded by what astronomers call a protoplanetary disk – a swirling "pancake" of hot gas and dust from which planets form. The exact processes that give rise to stars and planetary systems, however, are still poorly understood.

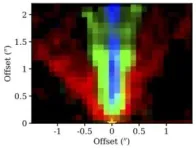

A team of astronomers led by University of Arizona researchers has used NASA's James Webb Space Telescope to obtain some of the most detailed insights into the forces that shape protoplanetary disks. The observations offer glimpses into what our solar system may have looked like 4.6 billion years ago.

Specifically, the team was able to trace so-called disk winds in unprecedented detail. These winds are streams of gas blowing from the planet-forming disk out into space. Powered largely by magnetic fields, these winds can travel tens of miles in just one second. The researchers' findings, published in Nature Astronomy, help astronomers better understand how young planetary systems form and evolve.

According to the paper's lead author, Ilaria Pascucci, a professor at the U of A's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, one of the most important processes at work in a protoplanetary disk is the star eating matter from its surrounding disk, which is known as accretion.

"How a star accretes mass has a big influence on how the surrounding disk evolves over time, including the way planets form later on," Pascucci said. "The specific ways in which this happens have not been understood, but we think that winds driven by magnetic fields across most of the disk surface could play a very important role."

Young stars grow by pulling in gas from the disk that's swirling around them, but in order for that to happen, gas must first shed some of its inertia. Otherwise, the gas would consistently orbit the star and never fall onto it. Astrophysicists call this process "losing angular momentum," but how exactly that happens has proved elusive.

To better understand how angular momentum works in a protoplanetary disk, it helps to picture a figure skater on the ice: Tucking her arms alongside her body will make her spin faster, while stretching them out will slow down her rotation. Because her mass doesn't change, the angular momentum remains the same.

For accretion to occur, gas across the disk has to shed angular momentum, but astrophysicists have a hard time agreeing on how exactly this happens. In recent years, disk winds have emerged as important players funneling away some gas from the disk surface – and with it, angular momentum – which allows the leftover gas to move inward and ultimately fall onto the star.

Because there are other processes at work that shape protoplanetary disks, it is critical to be able to distinguish between the different phenomena, according to the paper's second author, Tracy Beck at NASA's Space Telescope Science Institute.

While material at the inner edge of the disk is pushed out by the star's magnetic field in what is known as X-wind, the outer parts of the disk are eroded by intense starlight, resulting in so-called thermal winds, which blow at much slower velocities.

"To distinguish between the magnetic field-driven wind, the thermal wind and X-wind, we really needed the high sensitivity and resolution of JWST (the James Webb Space Telescope)," Beck said.

Unlike the narrowly focused X-wind, the winds observed in the present study originate from a broader region that would include the inner, rocky planets of our solar system – roughly between Earth and Mars. These winds also extend farther above the disk than thermal winds, reaching distances hundreds of times the distance between Earth and the sun.

"Our observations strongly suggest that we have obtained the first images of the winds that can remove angular momentum and solve the longstanding problem of how stars and planetary systems form," Pascucci said.

For their study, the researchers selected four protoplanetary disk systems, all of which appear edge-on when viewed from Earth.

"Their orientation allowed the dust and gas in the disk to act as a mask, blocking some of the bright central star's light, which otherwise would have overwhelmed the winds," said Naman Bajaj, a graduate student at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory who contributed to the study.

By tuning JWST's detectors to distinct molecules in certain states of transition, the team was able to trace various layers of the winds. The observations revealed an intricate, three-dimensional structure of a central jet, nested inside a cone-shaped envelope of winds originating at progressively larger disk distances, similar to the layered structure of an onion. An important new finding, according to the researchers, was the consistent detection of a pronounced central hole inside the cones, formed by molecular winds in each of the four disks.

Next, Pascucci's team hopes to expand these observations to more protoplanetary disks, to get a better sense of how common the observed disk wind structures are in the universe and how they evolve over time.

"We believe they could be common, but with four objects, it's a bit difficult to say," Pascucci said. "We want to get a larger sample with James Webb, and then also see if we can detect changes in these winds as stars assemble and planets form."

For a complete list of authors, please see the paper, "The nested morphology of disk winds from young stars revealed by JWST/NIRSpec observations," Nature Astronomy (DOI 10.1038/s41550-024-02385-7). Funding for this work was provided by NASA and the European Research Council.

END

Winds of change: James Webb Space Telescope reveals elusive details in young star systems

Astronomers have discovered new details of gas flows that sculpt planet-forming disks and shape them over time, offering a glimpse into how our own solar system likely came to be.

2024-10-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UC Merced co-leads initiative to combat promotion and tenure bias against Black and Hispanic faculty

2024-10-04

Black and Hispanic faculty members seeking promotion at research universities face career-damaging biases, with their scholarly production judged more harshly than that of their peers, according to a groundbreaking initiative co-led by the University of California, Merced that aims to uncover the roots of these biases and develop strategies for change.

Junior professors are generally evaluated and voted on for promotion and tenure by committees comprising senior colleagues. In one of the studies conducted by the research team, results suggest that faculty from underrepresented minorities received 7% more negative votes from ...

Addressing climate change and inequality: A win-win policy solution

2024-10-04

Climate change and economic inequality are deeply interconnected, with the potential to exacerbate each other if left unchecked. A new study published in Nature Climate Change sheds light on this critical relationship using data from eight large-scale Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) to examine the distributional impacts of climate policies and climate risks. The study provides robust evidence that climate policies aligned with the Paris Agreement can mitigate long-term inequality while addressing climate change.

Led by Johannes Emmerling, Senior Scientist at the Euro-Mediterranean ...

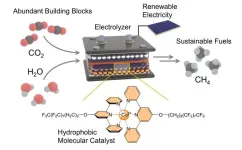

Innovative catalyst produces methane using electricity

2024-10-04

Researchers at the University of Bonn and University of Montreal have developed a new type of catalyst and used it in their study to produce methane out of carbon dioxide and water in a highly efficient way using electricity. Methane can be used, for example, to heat apartments or as a starting material in the chemical industry. It is also the main component of natural gas. If it is produced using green electricity, however, it is largely climate neutral. The insights gained from the model system studied by the researchers can be transferred to large-scale technical ...

Liver X receptor beta: a new frontier in treating depression and anxiety

2024-10-04

Houston, Texas – In a state-of-the-art Bench to Bedside review published in the journal Brain Medicine (Genomic Press), researchers Dr. Xiaoyu Song and Professor Jan-Åke Gustafsson from the University of Houston and Karolinska Institutet (Sweden) shed light on the therapeutic potential of liver X receptor beta (LXRβ) in treating depression and anxiety. This comprehensive analysis marks a significant step forward in understanding the molecular underpinnings of mental health disorders and potentially revolutionizing their treatment.

LXRβ, a nuclear receptor initially known for its role in cholesterol metabolism and inflammation, is now emerging as a crucial ...

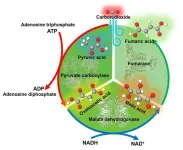

Improving fumaric acid production efficiency through a ‘more haste, less speed’ strategy

2024-10-04

As plastic waste continues to build up faster than it can decompose, the need for biodegradable solutions is evident.

Previously, Professor Yutaka Amao and his team at Osaka Metropolitan University’s Research Center for Artificial Photosynthesis succeeded in synthesizing fumaric acid, a raw material for biodegradable plastics from biomass-derived pyruvic acid and carbon dioxide. However, the fumaric acid production process reported earlier has a problem with producing undesirable substances as byproducts in addition to L-malic acid, which is ...

How future heatwaves at sea could devastate UK marine ecosystems and fisheries

2024-10-04

The oceans are warming at an alarming rate. 2023 shattered records across the world’s oceans, and was the first time that ocean temperatures exceeded 1oC over pre-industrial levels. This led to the emergence of a series of marine heatwave events across both hemispheres, from the waters around Japan, around South America, and across the wider North Atlantic. Marine heatwaves are periods of extremely warm sea temperatures that can form in quite localized hot spots but also span large parts of ocean ...

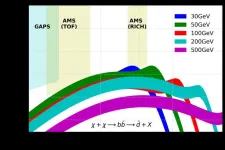

Glimmers of antimatter to explain the "dark" part of the universe

2024-10-04

One of the great challenges of modern cosmology is to reveal the nature of dark matter. We know it exists (it constitutes over 85% of the matter in the Universe), but we have never seen it directly and still do not know what it is. A new study published in JCAP has examined traces of antimatter in the cosmos that could reveal a new class of never-before-observed particles, called WIMP (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles), which could make up dark matter. The study suggests that some recent observations ...

Kids miss out on learning to swim during pandemic, widening racial and ethnic disparities

2024-10-04

Nearly three out of four kids in Chicago had no swimming lessons in summer of 2022, with significant racial and ethnic differences, according to a parent survey from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago published in Pediatrics. Black and Hispanic/Latine kids were disproportionately affected (85 percent and 82 percent, respectively), compared to white kids (64 percent).

The most common reasons for not getting swimming lessons also differed among racial and ethnic groups. Parents of White kids reported they ...

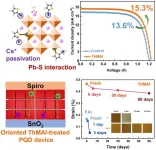

DGIST restores the performance of quantum dot solar cells as if “flattening crumpled paper!”

2024-10-04

□ Professor Jongmin Choi’s team from the Department of Energy Science and Engineering at DGIST (President Kunwoo Lee) conducted joint research with Materials Engineering and Convergence Technology Professor Tae Kyung Lee from Gyeongsang National University and Applied Chemistry Professor Younghoon Kim from Kookmin University. The researchers developed a new method to improve both the performance and the stability of solar cells using “perovskite quantum dots.” They developed longer-lasting solar cells by addressing the issue of distortions on the surface of quantum dots, which deteriorate the ...

Hoarding disorder: ‘sensory CBT’ treatment strategy shows promise

2024-10-04

Rehearsing alternative outcomes of discarding through imagery rescripting shows promise as a treatment strategy for people who hoard, a study by UNSW psychology researchers has shown.

Hoarding disorder is a highly debilitating condition that worsens with age. People who hoard form intense emotional attachments to objects, accumulate excessive clutter, and have difficulty discarding possessions. Many avoid treatment.

People who hoard also experience more frequent, intrusive and distressing mental images in their daily lives, says Mr Isaac Sabel from the Grisham Research Lab, an experimental clinical psychology research group at UNSW Sydney.

“Negative ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Winds of change: James Webb Space Telescope reveals elusive details in young star systemsAstronomers have discovered new details of gas flows that sculpt planet-forming disks and shape them over time, offering a glimpse into how our own solar system likely came to be.