(Press-News.org) Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) remains the most aggressive and deadly type of breast cancer, but new findings from cancer researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, are pointing the way toward therapeutic strategies that could be tested in clinical trials in the future. Using patient-derived samples in pre-clinical work, researchers discovered that by combining two therapeutic agents they could nudge TNBC cells into a more treatable state. Findings are published in Nature.

“When combined, these therapeutic agents can hijack signals that occur naturally in the body to eliminate breast cells after the cessation of lactation to kill these aggressive cancer cells,” said senior author Karen Cichowski, PhD, of the Division of Genetics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). “Our results provide compelling support for the development of clinical trials to test whether combining these agents could benefit patients with TNBC.”

Specifically, the researchers discovered that that by combining two types of agents known as EZH2 and AKT inhibitors, they could coax TNBC cells to differentiate. Once the cells are differentiated, these agents kill tumor cells by triggering a process similar to involution, which normally occurs when breast tissue returns to a non-lactating state after a mother stops producing breast milk. The researchers also used machine learning to predict patient responses—another step that could help set the stage for clinical trials in patients.

In future studies, the researchers are interested in exploring whether similar drug combinations may be effective in other tumor types.

Authorship: In addition to Cichowski, BWH authors include Amy E Schade, Naiara Perurena, Yoona Yang, Carrie L Rodriguez, Anjana Krishnan, Alycia Gardner, Patrick Loi, Yilin Xu, Van TM Nguyen, GM Mastellone, Natalie F Pilla, Marina Watanabe, Keiichi Ota, Rachel A Davis, Kaia Mattioli, Dongxi Xiang, Zhe Li, and Sandro Santagata.

Disclosures: Cichowski is an advisor at Genentech and serves on the scientific advisory board of Erasca, Inc. Disclosures for other authors can be found in the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge and the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research to the SPECIFICANCER team (KC) and a DOD BC201085P1 Transformative Breast Cancer Consortium Award.

Paper cited: Schade AE et al. “AKT and EZH2 inhibitors kill TNBCs by hijacking mechanisms of involution” Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08031-6

###

About Mass General Brigham

Mass General Brigham is an integrated academic health care system, uniting great minds to solve the hardest problems in medicine for our communities and the world. Mass General Brigham connects a full continuum of care across a system of academic medical centers, community and specialty hospitals, a health insurance plan, physician networks, community health centers, home care, and long-term care services. Mass General Brigham is a nonprofit organization committed to patient care, research, teaching, and service to the community. In addition, Mass General Brigham is one of the nation’s leading biomedical research organizations with several Harvard Medical School teaching hospitals. For more information, please visit massgeneralbrigham.org.

END

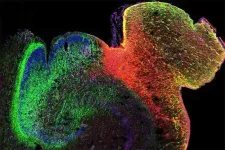

A UCLA-led study has provided an unprecedented look at how gene regulation evolves during human brain development, showing how the 3D structure of chromatin — DNA and proteins — plays a critical role. This work offers new insights into how early brain development shapes lifelong mental health.

The study, published in Nature, was led by Dr. Chongyuan Luo at UCLA and Dr. Mercedes Paredes at UC San Francisco, in collaboration with researchers from the Salk Institute, UC San Diego and Seoul National University. It created the first map of DNA modification in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex — two regions ...

New research from the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience published this week in Nature has identified a key step in how neurons encode information on timescales that match learning.

A timing mismatch

Learning takes seconds to minutes. However, the best-understood mechanisms of how the brain encodes information happen at speeds closer to neural activity—around 1000 times faster. These mechanisms, known as Hebbian plasticity, suggest that if two connected neurons are both active within a hundredth of a second, then the connection between the two neurons is strengthened. In this ...

HOUSTON ―Researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have demonstrated that patients with metastatic non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring specific mutations in the STK11 and/or KEAP1 tumor suppressor genes were more likely to benefit from adding the immunotherapy tremelimumab to a combination of durvalumab plus chemotherapy to overcome treatment resistance typically seen in this patient population.

Study results, published today in Nature, identify ...

Scientists discover viral trapdoor blocking HIV and herpes

Ghent, 10 October 2024 – A group of researchers led by Xavier Saelens and Sven Eyckerman at the VIB-UGent Center for Medical Biotechnology discovered how a protein linked to the human immune system wards off HIV-1 and herpes simplex virus-1 by assembling structures in the cell that lure in these viruses and then trap them or even take them apart. The research was spearheaded by first author George Moschonas, published in Cell Host and Microbe, and could be used to devise new strategies to combat these viruses.

The innate immune system of the human body can sense and respond to viruses by ...

How bladder cancer originates and progresses has been illuminated as never before in a study led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine and the New York Genome Center. The researchers found that antiviral enzymes that mutate the DNA of normal and cancer cells are key promoters of early bladder cancer development, and that standard chemotherapy is also a potent source of mutations. The researchers also discovered that overactive genes within abnormal circular DNA structures in tumor cells genes drive bladder cancer resistance to therapy. These findings are novel insights into bladder cancer biology and point to new therapeutic strategies for this ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A recently developed electronic tongue is capable of identifying differences in similar liquids, such as milk with varying water content; diverse products, including soda types and coffee blends; signs of spoilage in fruit juices; and instances of food safety concerns. The team, led by researchers at Penn State, also found that results were even more accurate when artificial intelligence (AI) used its own assessment parameters to interpret the data generated by the electronic tongue.

The researchers published their results today (Oct. 9) in Nature.

According to the researchers, ...

We often only realize how important our sense of smell is when it is no longer there: food hardly tastes good, or we no longer react to dangers such as the smell of smoke. Researchers at the University Hospital Bonn (UKB), the University of Bonn and the University of Aachen have investigated the neuronal mechanisms of human odor perception for the first time. Individual nerve cells in the brain recognize odors and react specifically to the smell, the image and the written word of an object, for example a banana. The results of this study close a long-standing knowledge gap between animal and human odor research and have now been published in the renowned ...

ST. LOUIS, MO, October 9, 2024 - Plant scientists at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center and the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology have been awarded a four-year National Science Foundation (NSF) Enabling Discovery through GEnomics (EDGE) grant to advance their understanding of sphagnum moss, a crucial component of peatlands and a vital player in global ecosystems. The collaborative research team will develop genetic and genomic resources to study sphagnum's life cycle, growth, and adaptation to various environmental conditions.

Sphagnum ...

Plastic pollution – tiny bits of plastic, smaller than a grain of sand – is everywhere, a fact of life that applies even to newborn rodents, according to a Rutgers Health study published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Researchers have long understood that micro- and nanoplastic particles (MNPs), which enter the environment through oxidation and natural degradation of consumer products, are easily deposited in the human body through inhalation, absorption and diet.

Experts also understand that these pollutants can cross the placental barrier and deposit ...

A University of Queensland-led study has failed to find any strong links between drinking coffee during pregnancy and neurodevelopmental difficulties in children, but researchers are advising expectant mothers to continue following medical guidelines on caffeine consumption.

Dr Gunn-Helen Moen and PhD student Shannon D’Urso from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience (IMB) led an in-depth genetic analysis of data from tens of thousands of families in Norway.

“Scandinavians are some of the biggest coffee consumers in the world, drinking at least 4 cups a day, with little stigma about drinking coffee during pregnancy,” ...