(Press-News.org) If you’ve ever struggled to reduce your carb intake, ancient DNA might be to blame.

It has long been known that humans carry multiple copies of a gene that allows us to begin breaking down complex carbohydrate starch in the mouth, providing the first step in metabolizing starchy foods like bread and pasta. However, it has been notoriously difficult for researchers to determine how and when the number of these genes expanded. Now a new study led by The University of Buffalo (UB) and The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) showcases how early duplications of this gene set the stage for the wide genetic variation that still exists today, influencing how effectively humans digest starchy foods.

The study's findings, reported in the Oct. 17 advanced online issue of Science, reveal that the duplication of this gene—known as the salivary amylase gene (AMY1) —may not only have helped shape human adaptation to starchy foods, but may have occurred as far back as more than 800,000 years ago, long before the advent of farming.

"The idea is that the more amylase genes you have, the more amylase you can produce and the more starch you can digest effectively,” said the study's corresponding author, Omer Gokcumen, PhD, professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, within the UB College of Arts and Sciences. Amylase, the researchers explained, is an enzyme that not only breaks down starch into glucose, but also gives bread its taste.

Gokcumen and his colleagues, including co-senior author, Charles Lee, professor and Robert Alvine Family Endowed Chair at JAX, used optical genome mapping and long-read sequencing, a methodological breakthrough crucial to mapping the AMY1 gene region in extraordinary detail. Traditional short-read sequencing methods struggle to accurately distinguish between gene copies in this region due to their near-identical sequence. However, long-read sequencing allowed Gokcumen and Lee to overcome this challenge in present-day humans, providing a clearer picture of how AMY1 duplications evolved.

Ancient hunter-gatherers and even Neanderthals already had multiple AMY1 copies

Analyzing the genomes of 68 ancient humans, including a 45,000-year-old sample from Siberia, the research team found that pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers already had an average of four to eight AMY1 copies per diploid cell, suggesting that humans were already walking around Eurasia with a wide variety of high AMY1 copy numbers well before they started domesticating plants and eating excess amounts of starch.

The study also found that AMY1 gene duplications occurred in Neanderthals and Denisovans. “This suggests that the AMY1 gene may have first duplicated more than 800,000 years ago, well before humans split from Neanderthals and much further back than previously thought,” said Kwondo Kim, one of the lead authors on this study from the Lee Lab at JAX.

“The initial duplications in our genomes laid the groundwork for significant variation in the amylase region, allowing humans to adapt to shifting diets as starch consumption rose dramatically with the advent of new technologies and lifestyles,” said Gokcumen.

The seeds of genetic variation

The initial duplication of AMY1 was like the first ripple in a pond, creating a genetic opportunity that later shaped our species. As humans spread across different environments, the flexibility in the number of AMY1 copies provided an advantage for adapting to new diets, particularly those rich in starch.

"Following the initial duplication, leading to three AMY1 copies in a cell, the amylase locus became unstable and began creating new variations," said Charikleia Karageorgiou, one of the lead authors of the study at UB. “From three AMY1 copies, you can get all the way up to nine copies, or even go back to one copy per haploid cell."

The complicated legacy of farming

The research also highlights how agriculture impacted AMY1 variation. While early hunter-gatherers had multiple gene copies, European farmers saw a surge in the average number of AMY1 copies over the past 4,000 years, likely due to their starch-rich diets. Gokcumen’s previous research showed that domesticated animals living alongside humans, such as dogs and pigs, also have higher AMY1 copy numbers compared to animals not reliant on starch-heavy diets.

"Individuals with higher AMY1 copy numbers were likely digesting starch more efficiently and having more offspring,” Gokcumen said. “Their lineages ultimately fared better over a long evolutionary timeframe than those with lower copy numbers, propagating the number of the AMY1 copies."

The findings track with a University of California, Berkeley-led study published last month in Nature, which found that humans in Europe expanded their average number of AMY1 copies from four to seven over the last 12,000 years.

“Given the key role of AMY1 copy number variation in human evolution, this genetic variation presents an exciting opportunity to explore its impact on metabolic health and uncover the mechanisms involved in starch digestion and glucose metabolism,” said Feyza Yilmaz, an associate computational scientist at JAX and a lead author of the study. “Future research could reveal its precise effects and timing selection, providing critical insights into genetics, nutrition, and health.”

The research was a collaboration with the University of Connecticut Health Center and was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health – National Human Genome Research Institute.

END

The biosynthetic pathway of specific steroidal compounds in nightshade plants (such as potatoes, tomatoes and eggplants) starts with cholesterol. Several studies have investigated the enzymes involved in the formation of steroidal glycoalkaloids. Although the genes responsible for producing the scaffolds of steroidal specialized metabolites are known, successfully reconstituting of these compounds in other plants has not yet been achieved. The project group ‘Specialized Steroid Metabolism in Plants’ in the Department of Natural Product Biosynthesis, led by Prashant Sonawane, who is now Assistant ...

A major new study reveals that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from forest fires have surged by 60% globally since 2001, and almost tripled in some of the most climate-sensitive northern boreal forests.

The study, led by the University of East Anglia (UEA) and published today in Science, grouped areas of the world into ‘pyromes’ - regions where forest fire patterns are affected by similar environmental, human, and climatic controls - revealing the key factors driving recent increases in forest fire activity.

It is one of the first studies to look globally at the differences between forest ...

A new study shows that an artificial intelligence (AI) tool can help people with different views find common ground by more effectively summarizing the collective opinion of the group than humans. By producing statements that convey the majority opinion, while incorporating the minority’s perspective, the AI produced outputs that participants preferred—and that they rated as more informative, clear, and unbiased, compared to those written by human mediators. Human society is enriched by a plurality of viewpoints, but agreement is a prerequisite for people to act collectively. ...

The health of American democracy is facing challenges, with experts pointing to recent democratic backsliding, deepening partisan divisions, and growing anti-democratic attitudes and rhetoric. In this issue of Science, Research Articles, a Policy Forum, a Science News feature, and a related Editorial highlight how the tools of science and technology are being used to address this growing concern and how the upcoming U.S. presidential election could impact U.S. science.

In one research study in this special issue, Jonathan Chu and colleagues sought to understand whether understandings ...

As climate change promotes fire-favorable weather, climate-driven wildfires in extratropical forests have overtaken tropical forests as the leading source of global fire emissions, researchers report. The findings raise urgent concerns about the future of forest carbon sinks under climate change. Fire has long played a role in shaping Earth's forests and regulating carbon storage in ecosystems. However, anthropogenic climate change has intensified fire-prone weather, leading to an increase in burned areas and carbon emissions, particularly in forested regions. These fires not only reduce forests' ability to absorb carbon but also disrupt ecosystems, harm biodiversity, and pose significant ...

Studies of chemicals in our blood typically capture only a small and unknown fraction of the entire chemical universe. Now, a new approach aims to change that. In a study involving blood samples of pregnant women collected between 2006 and 2008, researchers report having quantified many complex mixtures of chemicals that may pose neurotoxic risks, even when the individual chemicals were present at seemingly harmless levels. “The quantification of 294 to 473 chemicals in plasma is a major improvement compared with the usual targeted analysis focusing on only few selective analytes,” wrote the authors. ...

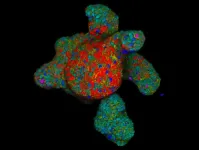

A multi-institutional group of researchers led by the Hubrecht Institute and Roche’s Institute of Human Biology has developed strategies to identify regulators of intestinal hormone secretion. In response to incoming food, these hormones are secreted by rare hormone producing cells in the gut and play key roles in managing digestion and appetite. The team has developed new tools to identify potential ‘nutrient sensors’ on these hormone producing cells and study their function. This could result in new strategies to interfere with the release of these hormones and provide avenues for the treatment of a variety of metabolic or gut motility disorders. The work will be presented ...

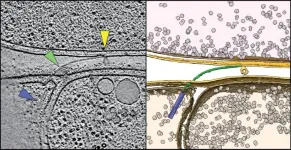

Countless bacteria call the vastness of the oceans home, and they all face the same problem: the nutrients they need to grow and multiply are scarce and unevenly distributed in the waters around them. In some spots they are present in abundance, but in many places they are sorely lacking. This has led a few bacteria to develop into efficient hunters to tap into new sources of sustenance in the form of other microorganisms.

Although this strategy is very successful, researchers have so far found only a few predatory bacterial species. One is the soil bacterium Myxococcus xanthus; ...

"In our everyday lives, we are exposed to a wide variety of chemicals that are distributed and accumulate in our bodies. These are highly complex mixtures that can affect bodily functions and our health," says Prof Beate Escher, Head of the UFZ Department of Cell Toxicology and Professor at the University of Tübingen. "It is known from environmental and water studies that the effects of chemicals add up when they occur in low concentrations in complex mixtures. Whether this is also the case in the human body has not yet been sufficiently investigated - this is precisely where our study comes in."

The extensive research work was based on over 600 blood samples from ...

Mpox in Africa was neglected during the previous outbreak, and requires urgent action and investment by leaders now to prevent global spread, claim experts from The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, ex-NZ Prime Minister Helen Clark, former Liberian President and Nobel Peace Prize winner Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and other global health specialists.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0003714

Article Title: Mpox: Neglect has led to a more dangerous virus now spreading across borders, harming and killing people. Leaders must take action to stop mpox now

Author Countries: ...