(Press-News.org)

In one of the largest-ever studies of DNA and brain volume, researchers have identified 254 genetic variants that shape key structures in the “deep brain,” including those that control memory, motor skills, addictive behaviors and more. The findings were just published in the journal Nature Genetics.

The study is powered by the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) consortium, an international effort based at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, which unites more than 1,000 research labs across 45 countries to hunt for genetic variations that affect the brain’s structure and function.

“A lot of brain diseases are known to be partially genetic, but from a scientific point of view, we want to find the specific changes in the genetic code that cause these,” said Paul M. Thompson, PhD, associate director of the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute and principal investigator for ENIGMA.

“By conducting this research all over the world, we’re beginning to home in on what has been called ‘the genetic essence of humanity,’” he said.

Identifying brain regions that are larger or smaller in some groups (for example, people with a specific brain disease) compared to others can help scientists start to understand what causes dysfunction in the brain. Finding the genes that control the development of those brain regions offers a further clue about how to intervene.

In the present study, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, a team of 189 researchers from around the world collected DNA samples and magnetic resonance imaging brain scans, which measured volume in key subcortical regions — also known as the “deep brain” — from 74,898 participants. They then performed genome-wide association studies, or GWAS, an approach that can identify genetic variations linked to various traits or diseases, finding some gene-brain volume associations that carried a higher risk for Parkinson’s disease and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

“There is strong evidence that ADHD and Parkinson’s have a biological basis, and this research is a necessary step to understanding and eventually treating these conditions more effectively,” said Miguel Rentería, PhD, an associate professor of computational neurogenomics at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research (QIMR Berghofer) in Australia and principal investigator of the Nature Genetics study.

“Our findings suggest that genetic influences that underpin individual differences in brain structure may be fundamental to understanding the underlying causes of brain-related disorders,” he said.

Studying the deep brain

The researchers analyzed brain volume in key subcortical structures, including the brainstem, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, nucleus accumbens, putamen, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus and ventral diencephalon. These regions are critical for forming memories, regulating emotions, controlling movement, processing sensory data from the outside world, and responding to reward and punishment.

GWAS revealed 254 genetic variants associated with brain volume across those regions, explaining up to 10% of the observed differences in brain volume across participants in the study. While previous research has clearly linked certain regions with disease, such as the basal ganglia with Parkinson’s disease, the new study reveals which gene variants shape brain volume with greater precision.

“This paper, for the first time, pinpoints exactly where these genes act in the brain,” providing the beginnings of a roadmap for where to intervene said Thompson, who is also a professor of ophthalmology, pediatrics, neurology, psychiatry and the behavioral sciences, radiology, biomedical engineering and electrical engineering at the Keck School of Medicine.

The researchers note that the study is correlational, so more investigation is needed before genes can be causally linked with various diseases.

From Rentería’s group, doctoral candidate Luis García-Marín and postdoctoral researcher Adrian Campos, PhD, were the study’s first authors. In addition to data from ENIGMA, the researchers also used data from Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE), the UK Biobank and the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. Summary statistics are available for researchers to download from the ENIGMA consortium.

About this research

In addition to Thompson and Rentería, the study’s other USC authors include Neda Jahanshad and Sophia I. Thomopoulos from the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Keck School of Medicine of USC. A full list of authors and their affiliations can be found in the online publication.

This work was supported by federal and private agencies across the world, including the National Institutes of Health, under grants R01AG058854, U01AG068057, R01NS107513 and R01MH116147. A full list of funders can be found in the online publication.

END

Food production is one of the pillars of human civilization and underlies many of the changes caused by humans on planet’s landscapes. Producing food and getting it to people’s plates entails a significant expenditure of energy and resources. Unfortunately, approximately one third of all food produced globally is not consumed and discarded. Hence, to build sustainable societies, it is essential to minimize food waste.

In Japan, based on estimates reported by governmental institutions, an astonishing 2.47 megatons of food waste was generated in ...

Many women who receive chemotherapy experience a decreased ability to remember, concentrate, and/or think—commonly referred to as “chemo-brain” or “brain fog”—both short- and long-term. In a recent clinical trial of women initiating chemotherapy for breast cancer, those who simultaneously started an aerobic exercise program self-reported greater improvements in cognitive function and quality of life compared with those receiving standard care. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

The study, called the Aerobic exercise and ...

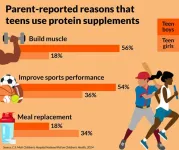

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Protein bars, shakes and powders are increasingly popular among adults – but many teens may be jumping on the bandwagon too.

Two in five parents say their teen consumed protein supplements in the past year, according to the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health. The trend was more common among teen boys who were also more likely to take protein supplements every day or most days, parents reported.

“Protein is part of a healthy diet but it can be hard for parents to tell if ...

SAN DIEGO, California, 21 October 2024. In an illuminating Genomic Press Interview published today, Dr. Stephanie Knatz Peck, Associate Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), unveils her groundbreaking work in eating disorder treatment and psychedelic research. The interview, featured in the journal Psychedelics, offers an intimate look at Dr. Knatz Peck's journey from personal struggle with an eating disorder to becoming a leading innovator in the field.

Dr. Knatz Peck's research ...

In stalk-eyed flies, longer eyestalks attract the ladies. Females prefer males with longer eyestalks, and other males are less likely to fight them for access to females. But some males have a copy of the X chromosome which always causes short eyestalks. Scientists investigating why this mutation hasn’t died out, despite sexual selection, have discovered that the flies could be compensating for their shorter eyestalks with increased aggression.

“It's the first time I'm aware of that there's ...

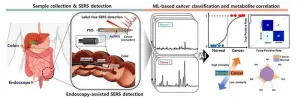

A research team led by Dr. Ho Sang Jung of the Advanced Bio and Healthcare Materials Research Division at the Korea Institute of Materials Science has developed an innovative sensor material that amplifies the optical signals of cancer metabolites in body fluids (saliva, mucus, urine, etc.) and analyzes them using artificial intelligence to diagnose cancer.

This technology quickly and sensitively detects metabolites and changes in cancer patients' body fluids, providing a non-invasive way to diagnose cancer instead of traditional blood draws or biopsies. In collaboration with Professor Soo Woong ...

Inuit children in Nunavut, Canada, are being overdiagnosed for macrocephaly and underdiagnosed for microcephaly, two neurological conditions measured by head size, because of reliance on World Health Organization (WHO) growth curves, according to new research in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.230905.

“Clinicians must be able to identify children with potential medical issues appropriately, without underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis at the extremes of head circumference measurements,” writes Dr. Kristina Joyal, a pediatric neurologist, University of Manitoba and University of Saskatchewan, ...

New poll shows nearly two-thirds of adults (61%) expect global research universities, such as the University of Cambridge, to come up with new innovations that will help to reduce the effects of climate change.

Alternative fuels for cars and planes, improved batteries and capturing more carbon will have the greatest impact on climate change, the UK public believe.

Respondents want the government to listen to universities when making climate policy, ahead of all other interest groups tested.

Cambridge University is playing a leading role in ...

PHILADELPHIA — While recovering from major surgery, Black patients may be less likely to receive certain multimodal analgesia options and more likely to receive oral opioids than white patients, according to research being presented at the ANESTHESIOLOGY® 2024 annual meeting.

Multimodal analgesia, which uses multiple types of pain medication to reduce pain, has been shown to be more effective at treating postsurgical pain than a single medication alone, particularly after complex surgeries such ...

PHILADELPHIA — People who experience poor sleep in the month before surgery may be more likely to develop postoperative delirium, according to new research being presented at the ANESTHESIOLOGY® 2024 annual meeting.

Postoperative delirium is a change in mental function that can cause confusion and occurs in up to 15% of surgical patients. In certain high-risk patients, such as those with hip fractures, the incidence can be even higher. It is a significant complication in older adults. Pain, age, stress, anxiety and insomnia are known to contribute to the risk for postoperative delirium. The researchers believe this study is the first to assess sleep quality ...