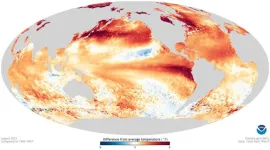

(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. – The El Niño event, a huge blob of warm ocean water in the tropical Pacific Ocean that can change rainfall patterns around the globe, isn't just a modern phenomenon.

A new modeling study from a pair of Duke University researchers and their colleagues shows that the oscillation between El Niño and its cold counterpart, La Niña, was present at least 250 million years in the past, and was often of greater magnitude than the oscillations we see today.

These temperature swings were more intense in the past, and the oscillation occurred even when the continents were in different places than they are now, according to the study, which appears the week of Oct. 21 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"In each experiment, we see active El Niño Southern Oscillation, and it's almost all stronger than what we have now, some way stronger, some slightly stronger," said Shineng Hu, an assistant professor of climate dynamics in Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment.

Climate scientists study El Niño, a giant patch of unusually warm water on either side of the equator in the eastern Pacific Ocean, because it can alter the jet stream, drying out the U.S. northwest while soaking the southwest with unusual rains. Its counterpart, the cool blob La Niña, can push the jet stream north, drying out the southwestern U.S., while also causing drought in East Africa and making the monsoon season of South Asia more intense.

The researchers used the same climate modeling tool used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to try to project climate change into the future, except they ran it backwards to see the deep past.

The simulation is so computationally intense that the researchers couldn't model each year continuously from 250 million years ago. Instead they did 10-million-year 'slices' -- 26 of them.

"The model experiments were influenced by different boundary conditions, like different land-sea distribution (with the continents in different places), different solar radiation, different CO2," Hu said. Each simulation ran for thousands of model years for robust results and took months to complete.

“At times in the past, the solar radiation reaching Earth was about 2% lower than it is today, but the planet-warming CO2 was much more abundant, making the atmosphere and oceans way warmer than present, Hu said.” In the Mezozoic period, 250 million years ago, South America was the middle part of the supercontinent Pangea, and the oscillation occurred in the Panthalassic Ocean to its west.

The study shows that the two most important variables in the magnitude of the oscillation historically appear to be the thermal structure of the ocean and "atmospheric noise" of ocean surface winds.

Previous studies have focused on ocean temperatures mostly, but paid less attention to the surface winds that seem so important in this study, Hu said. "So part of the point of our study is that, besides ocean thermal structure, we need to pay attention to atmospheric noise as well and to understand how those winds are going to change."

Hu likens the oscillation to a pendulum. "Atmospheric noise – the winds – can act just like a random kick to this pendulum," Hu said. "We found both factors to be important when we want to understand why the El Niño was way stronger than what we have now."

"If we want to have a more reliable future projection, we need to understand past climates first," Hu said.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42488201) and the Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet (2022-03617). Simulations were conducted at the High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

CITATION: "Persistently Active El Niño–Southern Oscillation Since the Mesozoic," Xiang Li, Shineng Hu, Yongyun Hu, Wenju Cai, Yishuai Jin, Zhengyao Lu, Jiaqi Guo, Jiawenjing Lan, Qifan Lin, Shuai Yuan, Jian Zhang, Qiang Wei, Yonggang Liu, Jun Yang, Ji Nie. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Oct. 21, 2024. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2404758121

END

Weather-changing El Niño oscillation is at least 250 million years old

Modeling experiments show Pacific warm and cold patches persisted even when continents were in different places

2024-10-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Evolution in action: How ethnic Tibetan women thrive in thin oxygen at high altitudes

2024-10-21

Breathing thin air at extreme altitudes presents a significant challenge—there’s simply less oxygen with every lungful. Yet, for more than 10,000 years, Tibetan women living on the high Tibetan Plateau have not only survived but thrived in that environment.

A new study led by Cynthia Beall, Distinguished University Professor Emerita at Case Western Reserve University, answers some of those questions. The new research, recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), reveals how the Tibetan women’s physiological ...

Microbes drove methane growth between 2020 and 2022, not fossil fuels, study shows

2024-10-21

Microbes in the environment, not fossil fuels, have been driving the recent surge in methane emissions globally, according to a new, detailed analysis published Oct 28 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by CU Boulder researchers and collaborators.

“Understanding where the methane is coming from helps us guide effective mitigation strategies,” said Sylvia Michel, a senior research assistant at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research(INSTAAR) and a doctoral student in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at CU Boulder. “We need to know more about those emissions to ...

Re-engineered, blue light-activated immune cells penetrate and kill solid tumors

2024-10-21

HERSHEY, Pa. — Immunotherapies that mobilize a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer have become a treatment pillar. These therapies, including CAR T-cell therapy, have performed well in cancers like leukemias and lymphomas, but the results have been less promising in solid tumors.

A team led by researchers from the Penn State College of Medicine has re-engineered immune cells so that they can penetrate and kill solid tumors grown in the lab. They created a light-activated switch that controls protein function associated with cell ...

Rapidly increasing industrial activities in the Arctic

2024-10-21

The Arctic is threatened by strong climate change: the average temperature has risen by about 3°C since 1979 – almost four times faster than the global average. The region around the North Pole is home to some of the world’s most fragile ecosystems, and has experienced low anthropogenic disturbance for decades. Warming has increased the accessibility of land in the Arctic, encouraging industrial and urban development. Understanding where and what kind of human activities take place is key to ensuring sustainable development in the region – for both people and the environment. Until now, a comprehensive assessment of this part of the world has ...

Scan based on lizard saliva detects rare tumor

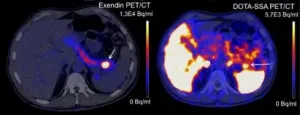

2024-10-21

A new PET scan reliably detects benign tumors in the pancreas, according to research led by Radboud university medical center. Current scans often fail to detect these insulinomas, even though they cause symptoms due to low blood sugar levels. Once the tumor is found, surgery is possible.

The pancreas contains cells that produce insulin, known as beta cells. Insulin is a hormone that helps the body absorb sugar from the blood and store it in places like muscle cells. This regulates blood sugar levels. In rare cases, the beta cells malfunction, resulting in a benign tumor called ...

Rare fossils of extinct elephant document the earliest known instance of butchery in India

2024-10-21

During the late middle Pleistocene, between 300 and 400 thousand years ago, at least three ancient elephant relatives died near a river in the Kashmir Valley of South Asia. Not long after, they were covered in sediment and preserved along with 87 stone tools made by the ancestors of modern humans.

The remains of these elephants were first discovered in 2000 near the town of Pampore, but the identity of the fossils, cause of death and evidence of human intervention remained unknown until now.

A team ...

Argonne materials scientist Mercouri Kanatzidis wins award from American Chemical Society for Chemistry of Materials

2024-10-21

Mercouri Kanatzidis, a materials scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and professor at Northwestern University, will receive the 2025 ACS Award in the Chemistry of Materials from the American Chemical Society, the nation’s leading professional organization of chemists.

The award “recognizes and encourages creative work in the chemistry of materials,” according to the citation.

At Argonne, Kanatzidis’s work has focused on the implications of a ...

Lehigh student awarded highly selective DOE grant to conduct research at DIII-D National Fusion Facility

2024-10-21

When it comes to sustainable energy, harnessing nuclear fusion is—for many—a holy grail of sorts. Unlike climate-warming fossil fuels, fusion offers a clean, nearly limitless source of energy by combining light atomic nuclei to form heavier ones, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process.

But it isn’t easy replicating and controlling the process that powers the sun.

“We eventually want to move to producing energy this way,” says Brian Leard ’21 ’25G, a ...

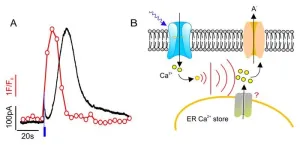

Plant guard cells can count environmental stimuli

2024-10-21

Plants control their water consumption via adjustable pores (stomata), which are formed from pairs of guard cells. They open their stomata when there is a sufficient water supply and enough light for carbon dioxide fixation through photosynthesis. In the dark and in the absence of water, however, they initiate the closing of the pores.

SLAC/SLAH-type anion channels in the guard cells are of central importance for the regulation of the stomata. This has been shown by the group of Professor Rainer Hedrich, biophysicist at Julius-Maximilians-Universität ...

UAMS researchers find ground beef packs bigger muscle-building punch than soy-based alternative

2024-10-21

When it comes to building muscle, not all proteins are created equal.

New research from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) reveals that 100% ground beef packs a bigger punch for muscle protein synthesis than a soy-based counterpart. In fact, the study suggests that a person would need double the amount of soy-based protein to achieve the same results.

Published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the study examined the anabolic response — how the body builds muscle — after consuming a 4-ounce beef patty versus one or two 4-ounce patties of a soy-based product. The results? Just one serving of beef did the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] Weather-changing El Niño oscillation is at least 250 million years oldModeling experiments show Pacific warm and cold patches persisted even when continents were in different places