(Press-News.org) EMBARGOED: NOT FOR RELEASE UNTIL 00.05 (UK TIME) WEDNESDAY 30 OCTOBER 2024

An international team of paleobiologists have found that the sinuses of ocean dwelling relatives of modern-day crocodiles prevented them from evolving into deep divers like whales and dolphins.

A new paper published today [30 October] in Royal Society Open Science suggests that thalattosuchians, which lived at the time of the dinosaurs, were stopped from exploring the deep due to their large snout sinuses.

Whales and dolphins (cetaceans) evolved from land-dwelling mammals to become fully aquatic over the course of around 10 million years. During this time, their bone-enclosed sinuses reduced and they developed sinuses and air sacs outside of their skulls.

This would have alleviated increases in pressure during deeper dives, allowing them to reach depths of hundreds (dolphins) and thousands (whales) of meters without damaging their skulls.

Thalattosuchians lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods and fall into two main groups. Teleosauridae, were similar to modern day gharial crocodiles, likely living in coastal waters and estuaries. Metriorhynchidae on the other hand were more fully adapted to life at sea, with streamlined bodies, flipper-like limbs and tail fins, amongst other marine adaptations.

Researchers from the University of Southampton, University of Edinburgh, and other institutions wanted to see if thalattosuchians had made similar sinus adaptations to whales and dolphins in their evolutionary journey from the land to the sea.

The team used computed tomography (a special kind of scan) to measure the sinuses of 11 thalattosuchian skulls, as well as the skulls of 14 modern crocodile species and six other fossil species.

Sinus changes

They found that braincase sinuses reduced across thalattosuchian evolution as they became more aquatic, in a similar way to those of whales and dolphins. The team think this is likely due to reasons relating to buoyancy, diving and feeding.

But the team also found that once thalattosuchians became fully aquatic, their snout sinuses expanded compared to their ancestors.

“The regression of braincase sinuses in thalattosuchians mirrors that of cetaceans, reducing during their semi-aquatic phases and then diminishing further as they became fully aquatic,” explains Dr Mark Young, lead author of the paper from the University of Southampton.

“Both groups also developed extracranial sinuses. But whereas the cetacean’s sinus system aids pressure regulation around the skull during deep dives, the expansive snout sinus systems of metriorhynchids precluded it from diving deeply.

“That’s because at greater depths, air within the sinuses would compress, causing discomfort, damage, or even collapse in the snout due to its inability to withstand or equalise the increasing pressure.”

Salt glands

While whales and dolphins have highly efficient kidneys that filter out salt from sea water, sea fairing reptiles and birds rely on salt glands to excrete salt from their systems.

The team believe that the larger, more complex snout sinuses of metriorhynchids may have helped to drain their salt glands, in a similar way to modern marine iguanas.

“A major problem for animals with salt glands is ‘encrustation’, where the salt dries and blocks the salt excreting ducts. Modern birds shake their heads to avoid this, while marine iguanas sneeze to force the salt out,” says Dr Young.

“We think that the expanded sinuses of metriorhynchids helped to expel excess salt. Birds, like metriorhynchids, have sinuses that exit the snout and pass under the eye and when their jaw muscles contract, it creates a bellows-like effect within their sinuses. For metriorhynchids, when the sinuses where subjected to this effect, it would have compressed the salt glands within the skull and created a sneeze-like effect, similar to modern marine iguanas.”

The study shows how major evolutionary transitions unfold and are shaped by species anatomy, biology and evolutionary history.

“It is fascinating to discover how ancient animals, such as thalattosuchians, adapted to a life in the ocean in their own unique way by showing both similarities and differences to modern day cetaceans,” says Dr Julia Schwab, a coauthor on the paper from the University of Manchester.

Dr Young concludes: “Thalattosuchians became extinct in the Early Cretaceous period, so we’ll never know for sure if given more evolutionary time they could have converged further with modern cetaceans or whether the need to mechanically drain their salts glands was an impassable barrier to further aquatic specialisation.”

Skull sinuses precluded extinct crocodile relatives from cetacean-style deep diving as they transitioned from land to sea is published in Royal Society Open Science.

The research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

Ends

Contact

Steve Williams, Media Manager, University of Southampton, press@soton.ac.uk or 023 8059 3212.

Notes for editors

Skull sinuses precluded extinct crocodile relatives from cetacean-style deep diving as they transitioned from land to sea is published in Royal Society Open Science. An advanced copy of the paper is available upon request.

For Interviews with Dr Mark Young please contact Steve Williams, Media Manager, University of Southampton press@soton.ac.uk or 023 8059 3212.

Images available here: https://safesend.soton.ac.uk/pickup?claimID=iVGSnVGRB8ReGhbF&claimPasscode=5ypsB8uVYhB9zwDx See description for credits.

Additional information

The University of Southampton drives original thinking, turns knowledge into action and impact, and creates solutions to the world’s challenges. We are among the top 100 institutions globally (QS World University Rankings 2025). Our academics are leaders in their fields, forging links with high-profile international businesses and organisations, and inspiring a 22,000-strong community of exceptional students, from over 135 countries worldwide. Through our high-quality education, the University helps students on a journey of discovery to realise their potential and join our global network of over 200,000 alumni. www.southampton.ac.uk

www.southampton.ac.uk/news/contact-press-team.page

Follow us on X: https://twitter.com/UoSMedia

END

Sinuses prevented prehistoric croc relatives from deep diving

2024-10-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

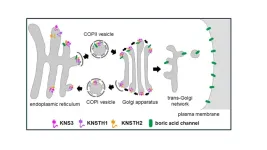

Spirited away: Key protein aids transport within plant cells

2024-10-30

Botanists have come to understand the channels and transporters involved in the uptake and transport of nutrients, yet how are they positioned where they need to be?

For example, plants need boron, which is taken into the cells by molecules known as the boric acid channel. But how do the proteins that form the channel make it to the plasma membrane?

A research group led by Professor Junpei Takano of Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Agriculture identified a mutant line of Arabidopsis thaliana in which the boric acid channels are not properly transported to the plasma membrane. The cause was a deficiency in the protein KAONASHI3 (KNS3); the name ...

Britain’s brass bands older than we thought and invented by soldiers from the Napoleonic Wars, new study reveals

2024-10-30

University of Cambridge media release

Britain’s brass bands older than we thought and invented by soldiers from the Napoleonic Wars, new study reveals

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 00:01 AM (UK TIME) ON WEDNESDAY 30TH OCTOBER 2024

Military musicians returning from the Napoleonic wars established Britain’s first brass bands earlier than previously thought, new research reveals. The study undermines the idea that brass bands were a civilian and exclusively northern creation.

It is widely believed that brass bands originated with coal miners and other industrial communities ...

The Lancet: Health threats of climate change reach record-breaking levels, as experts call for trillions of dollars spent on fossil fuels to be redirected towards protecting people’s health, lives and

2024-10-30

The Lancet: Health threats of climate change reach record-breaking levels, as experts call for trillions of dollars spent on fossil fuels to be redirected towards protecting people’s health, lives and livelihoods

New global findings in the 8th annual indicator report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change reveal that people in every country face record-breaking threats to health and survival from the rapidly changing climate, with 10 of 15 indicators tracking health threats reaching ...

‘Weekend warrior’ exercise pattern may equal more frequent sessions for lowering cognitive decline risk

2024-10-29

Just one or two sessions of physical activity at the weekend—a pattern of exercise dubbed ‘weekend warrior’---may be just as likely to lower the risk of cognitive decline, which can often precede dementia, as more frequent sessions, concludes research published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

And it may be more convenient and achievable for busy people as well, suggest the researchers.

It’s important to identify potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia because a 5-year delay in onset might halve its prevalence, they say, adding that nearly all the evidence to date comes from studies ...

Physical activity of any intensity linked to lower risk of death after dementia diagnosis

2024-10-29

Physical activity of any intensity after a diagnosis of dementia is associated with around a 30% lower risk of death, finds research published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

The findings prompt the researchers to conclude that those affected should be encouraged to keep up or start an exercise routine, especially as average life expectancy after a diagnosis of dementia may be only around 4-5 years.

Previously published research has linked physical activity with a lower risk of death in people with the disease, but these studies have focused on a single point in time. So it’s not clear if changes in the amount or intensity of physical ...

Brain changes seen in lifetime cannabis users may not be causal

2024-10-29

Lifetime cannabis use is associated with several changes in brain structure and function in later life, suggests an observational study, but these associations may not be causal, finds a genetic analysis of the same data, published in the open access journal BMJ Mental Health.

Some other unidentified factors may explain the differences found, say the researchers, who nevertheless emphasise that further research is needed to fully understand the effects of heavy use and cannabis potency on the brain.

Cannabis use has increased worldwide following its ...

For the love of suckers: Volunteers contribute to research on key freshwater fishes

2024-10-29

A new paper published today, led by Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, reveals how volunteers across Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan enabled researchers to gather seven years of data on the spawning migrations of suckers, an understudied yet essential group of freshwater fishes. Using observations collected by trained members of the public, the collaborative team of researchers have discovered that temperature is the primary trigger for sucker spawning migration, which can help inform conservation strategies in light of a changing climate.

“We believe that conservation of native, non-game fishes ...

Bill and Mary Anne Dingus commit $1M to fund Human Impacts on the Earth Fund at Rice

2024-10-29

Bill Dingus ’81, a Rice University alumnus, and his wife Mary Anne have pledged $1 million to support the university’s Human Impacts on the Earth Fund, dedicated to mitigating and addressing the negative environmental effects caused by human activities on the planet. Additionally, the Dingus family is matching other donors’ contributions to the fund up to $250,000.

The Dingus’ donation enables the launch of the Earth and Planetary Opportunities in Research (EXPLORE) program, a new initiative offered through the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences (EEPS) that allows undergraduates of any major hands-on experience in research projects ...

Most patients can continue GLP-1 anti-obesity drugs before surgery

2024-10-29

Most patients may continue to safely take glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists as prescribed before undergoing elective surgery and gastrointestinal endoscopies, according to new clinical guidance released today by five surgical and medical societies including the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), International Society of Perioperative Care of Patients with Obesity (ISPCOP), and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES).

The guidance, published online in Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases ...

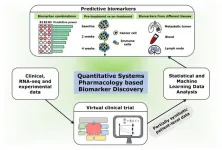

Computational tool developed to predict immunotherapy outcomes for patients with metastatic breast cancer

2024-10-29

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Using computational tools, researchers from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine have developed a method to assess which patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer could benefit from immunotherapy. The work by computational scientists and clinicians was published Oct. 28 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Immunotherapy is used to try to boost the body’s own immune system to attack cancer cells. However, only some patients respond to treatment, explains lead study author Theinmozhi Arulraj, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins: “It’s really important ...