By the 1990s, it was clear that the so-called Yixian Formation contained uniquely well preserved remains of dinosaurs, birds, mammals, insects, frogs, turtles and other creatures. Unlike the skeletal and often fragmentary fossils unearthed in most other places, many animals came complete with internal organs, feathers, scales, fur and stomach contents. It suggested some kind of sudden, unusual preservation process at work. The finds even included a cat-size mammal and a small dinosaur locked in mortal combat, stopped in mid-action when they died. The world’s first known non-avian feathered dinosaurs showed up—some so intact that scientists worked out the feathers’ colors. The discoveries revolutionized paleontology, clarifying the evolution of feathered dinosaurs, and proving without a doubt that modern birds are descended from them.

How did these fossils come to be so perfect? The leading hypothesis up to now has been sudden burial by volcanism, perhaps like the waves of hot ash from Mt. Vesuvius that entombed many citizens of Pompeii in A.D. 79. The Yixian deposits have been popularly dubbed the “Chinese Pompeii.”

A new study says the Pompeii idea is highly appealing―and totally wrong. Instead, the creatures were preserved by more mundane events including collapses of burrows and rainy periods that built up sediments that buried the dead in oxygen-free pockets. Earlier studies have suggested that multiple Pompeii-type events took place in pulses over about a million years. The current study uses newly sophisticated technology to date the fossils to a compact period of less than 93,000 years when nothing particular happened.

The study was just published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“These are probably the most important dinosaur discoveries of the last 120 years,” said study coauthor Paul Olsen, a paleontologist at the Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “But what was said about their method of preservation highlights an important human bias. That is, to ascribe extraordinary causes, i.e. miracles, to ordinary events when we don’t understand their origins. These [fossils] are just a snapshot of everyday deaths in normal conditions over a relatively brief time.”

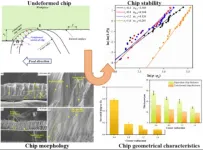

The Yixian Formation fossils come in two basic varieties: intact, perfectly articulated 3D skeletons from deposits formed mainly on land, and flattened but highly detailed carcasses found in lake sediments, some containing soft tissues.

To come up with fossil ages, the study’s lead author, Scott MacLennan of South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand, analyzed tiny grains of the mineral zircon, taken from both surrounding rocks and the fossils themselves. Within these, he measured ratios of radioactive uranium against lead, using a new, extremely precise method called chemical abrasion isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectroscopy, or CA-ID-TIMS. The fossils and surrounding material consistently dated to 125.8 million years ago, centered around a period of less than 93,000 years, though the exact number is not clear.

Further calculations showed that this timeframe contained three periods controlled by variations in the Earth’s orbit when the weather was relatively wet. This caused sediments to build up in lakes and on land far more rapidly than previously had been thought. Many deceased creatures were quickly buried, and oxygen that normally would fuel decomposition was sealed out. The sealing effect was fastest in lakes, resulting in the preservation of soft tissues.

The researchers rule out volcanism on multiple counts. Some previous studies have suggested that creatures were encased by lahars, fast-moving concrete-like slurries of mud that flow off volcanoes following eruptions. But lahars are extremely violent, said Olsen, and apt to rip apart any living or dead thing they encounter, so this explanation does not work.

Others have said pyroclastic flows―fast-moving waves of searing ash and poisonous gases á la Mt. Vesuvius―were responsible. These struck down residents of Pompeii, then wrapped the bodies in protective layers of material that preserved them as they were at the moment of death. Even when remains decayed, voids in the ashes remained, from which investigators have made lifelike plaster casts. The remains characteristically are curled in so-called pugilistic positions, torturously doubled over and with limbs severely drawn up, as blood boiled and bodies crumpled in the explosive heat. Victims of modern fires exhibit similar poses.

While there are in fact layers of volcanic ash, lava and intrusions of magma in the Yixian Formation, the remains there don’t match those of the unfortunate Pompeiians. For one thing, feathers, fur and everything else would almost certainly have been burned in a pyroclastic flow. For another, the dinosaurs and other animals are not in pugilistic positions; rather, many are found with arms and tails tucked cozily around their bodies, as if they were sleeping, perhaps dreaming dinosaur dreams, when death found them.

The evidence points instead to sudden burrow collapses, say the researchers. Cores of rock surrounding the skeletonized fossils generally consist of coarse grains, but grains immediately around and within the skeletons tend to be much finer. The researchers interpret this to mean that there was enough oxygen around for a while for bacteria or insects to degrade at least the animals’ skin and organs, and as this happened, whatever fine grains were in the surrounding material preferentially seeped in and filled the voids; the more decay-resistant bones remained intact. Even today, burrow collapses are a common cause of death for birds such as penguins, said Olsen. The frozen-in-time mammal-dinosaur battle may well have happened as the mammal invaded the dinosaur’s burrow to try and eat it or its babies, he said.

As to what caused the burrow collapses, this is speculation, he said. One thought: bigger dinosaurs (whose remains don’t appear here but who were almost certainly around) could have squished burrows simply by tromping around. Exceptionally rainy times could have helped destabilize the ground.

Olsen believes the Yixian Formation is not unique. “It’s just that there is no place else where such intense collecting has been done in this kind of environment,” he said. China has tried to limit for-profit fossil sales, but the market is still thriving, and huge government resources are going into development of tourism around the fossil sites.

Olsen’s personal Holy Grail is feathered dinosaurs, but these are exceedingly rare even in the richest deposits, he pointed out. “You have to dig out, say, 100,000 fish to find one feathered dinosaur, and no one is digging on the Yixian scale,” he said. Just in the eastern United States, several places that once had environments similar to the Yixian could yield such fossils, Olsen said. These include a rock quarry straddling the North Carolina-Virginia border where he has found thousands of perfectly preserved insects; sites in Connecticut where small excavations have shown promise; and a former quarry in North Bergen, N.J., now sandwiched between a highway and a strip mall that in the past yielded fabulously preserved fish and reptiles. Systematic excavations of such spots are more or less the size of a bathroom, he said.

“It takes enormous effort, which is expensive. And land is valuable in these areas,” he said. “So no one is doing it. At least not yet.”

The study was coauthored by Sean Kinney and Clara Chang of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and researchers from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, the Institute of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Princeton University.

# # #

Scientist contacts:

Paul Olsen polsen@ldeo.columbia.edu

Scott MacLennan scott.maclennan@wits.ac.za

More information: Kevin Krajick, Senior editor, science news, Columbia Climate School/Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory kkrajick@climate.columbia.edu 917-361-7766

END