(Press-News.org) Sometimes the holes, or pores, in the molecular structure of a chemical only appear in the presence of certain conditions or other ‘guest’ molecules. This affects the field of separation—one of the most important processes in industry—but researchers have only just begun to unravel this phenomenon

Researchers have explored how a particular chemical can selectively trap certain molecules in the cavities of its structure—even though in normal conditions it has no such cavities. This innovative material with now-you-see-them-now-you-don’t holes could lead to more efficient methods for separating and capturing chemicals right across industry.

A study describing the researchers’ findings was published in Nature Communications on September 27.

Separation of one kind of substance from another may sound straightforward as a topic of scientific investigation, but separation techniques are essential right across the economy as most things found in nature or manmade start off impure. From metal ores that are attached to unwanted rock within the field of mining, to distinguishing one material to be recycled from another, to drug delivery, environmental remediation, and gas storage, separation is at the heart of industrial modernity, and researchers are always on the hunt for better ways to do it.

In recent years, there has been increased interest in the fabrication of synthetic materials with pores—tiny holes—within the molecules themselves. These pores have specific sizes, shapes and other chemical attributes wherein only certain compounds whose characteristics match the ‘hole’ can fit. Think of the toddler’s classic hammer-and-bench toy, with square, circular, triangular and star-shaped wooden pegs that can each only fit in the correspondingly shaped hole in the bench. But in this case, fitting into a given pore depends on many more characteristics than just the shape of the toddler’s peg, allowing certain pores to select for some substances over others—what chemists call the “selectivity” of “molecular encapsulation,” or just selective encapsulation.

These synthetic porous materials of interest to chemists specializing in selective encapsulation include such buzzwords as metal-organic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks, hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks, and zeolites. But recently, one material in particular has piqued the interest of these researchers: macrocyclic molecular crystals. These are solids formed from large molecules with a significant number of atoms, often including elements like carbon, nitrogen or oxygen, arranged in a ring. The interior of this ring—in general—forms the cavity or pore where only certain substances “fit.”

On top of this, there are types of macrocyclic molecular crystals where the pore only appears in the presence of certain conditions such as heat or pressure or that of other, “guest” molecules. The rest of the time, there is no pore. This now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t type of cavity is called a “latent pore”.

“By designing materials with latent pores, we potentially can create systems that respond dynamically to environmental changes, enhancing their functionality and selectivity,” said Takeharu Haino, the lead author of the study and a materials scientist with the Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering at Hiroshima University. “The trouble is: until now, we didn’t always know why this latency was happening.”

To investigate what was going on, the Hiroshima researchers opted to have a deeper look at a particular type of latent-pore-bearing macrocyclic molecular crystal: planar tris(phenylisoxazolyl)benzene. The circular shape at its heart in this case comes from a ring of benzene, and it is termed planar because it comes in thin, tabular lamination shapes. They chose this one to investigate because other options involve very large molecules, but planar tris(phenylisoxazolyl)benzene is a simple flat molecule. It also has already been used in development of organic semiconductors, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and a number of other, proven, industrial applications.

They wanted to investigate the ability of the substance’s latent pores to separate two different forms of decalin. Also known as decahydronaphthalene, it is a colourless liquid at room temperature that is often used as a solvent, as well as in the production of various resins and polymers.

It also comes in two different structures—the same number of atoms, but arranged differently. There is cis-decalin, where a grouping of hydrogen and carbon atoms lies on the same side of the molecule, and also trans-decalin, where the hydrogen and the carbon atoms lie on opposite sides. This changes the decalin’s physical and chemical properties and so makes the substance a good candidate for exploring selective encapsulation.

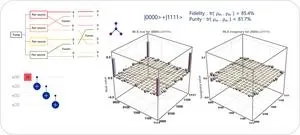

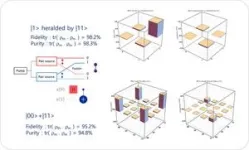

They used two types of x-ray diffraction analysis to explore the encapsulation process as it happened. In this form of investigation, x-rays are directed at the object of interest and the angles at which the rays are diffracted tell the researchers the object’s arrangement of atoms.

What they found was that planar tris(phenylisoxazolyl)benzene is a superb selector, correctly encapsulating the one form of decalin over the other 96 times out of a hundred. They also discovered that it was the intermolecular forces affecting the substance—the various interactions between the molecules that are strong but still weaker than atomic within the molecules that contributed to the pore’s stability and determines its remarkable selectivity. Other materials may be porous and selective but remain insufficiently stable for industrial applications. This substance ticks all the selective-encapsulation boxes.

This particular proof of concept could be used in a wide range of applications, such as gas entrapment, oil separation, and removal of trace elements from water, but the researchers want to seek out unique encapsulation functions that can only be achieved with latent pores.

And there remains a great deal of territory to explore explaining this “supramolecular” chemistry of latent pores. The researchers feel that they are just beginning their mapping of that territory.

###

About Hiroshima University

Since its foundation in 1949, Hiroshima University has striven to become one of the most prominent and comprehensive universities in Japan for the promotion and development of scholarship and education. Consisting of 12 schools for undergraduate level and 4 graduate schools, ranging from natural sciences to humanities and social sciences, the university has grown into one of the most distinguished comprehensive research universities in Japan. English website: https://www.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/en

END

When is a hole not a hole? Researchers investigate the mystery of 'latent pores'

2024-11-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

ETRI, demonstration of 8-photon qubit chip for quantum computation

2024-11-14

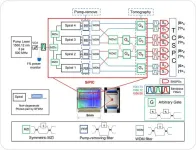

A group of South Korean researchers has successfully developed an integrated quantum circuit chip using photons (light particles). This achievement is expected to enhance the global competitiveness of the team in quantum computation research.

Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) announced that they have developed a system capable of controlling eight photons using a photonic integrated-circuit chip. With this system, they can explore various quantum phenomena, such as multipartite entanglement resulting from the interaction of the photons.

ETRI’s extensive research on silicon-photonic quantum ...

Remote telemedicine tool found highly accurate in diagnosing melanoma

2024-11-14

Collecting images of suspicious-looking skin growths and sending them off-site for specialists to analyze is as accurate in identifying skin cancers as having a dermatologist examine them in person, a new study shows.

According to the study authors, the findings add to evidence that such technology could help to reliably address diagnostic and treatment disparities for lower-income populations with limited access to dermatologists. It may also help dermatologists quickly catch cases of melanoma, a serious form of skin cancer that kills more than 8,000 Americans a year.

Their new system, which the researchers call SpotCheck, enables skin cancer specialists ...

New roles in infectious process for molecule that inhibits flu

2024-11-14

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have identified new roles for a protein long known to protect against severe flu infection – among them, raising the minimum number of viral particles needed to cause sickness.

The protein also helps prevent unfamiliar viruses from mutating after they infect a new host, the study found – meaning its absence during an immune response could enable an animal virus spilled over to people to adapt rapidly to human hosts.

The combined findings by scientists at The Ohio State University add up to potential trouble for people deficient in the protein, called IFITM3 – especially if an avian or swine flu were to gain ...

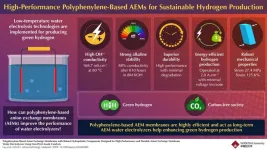

Transforming anion exchange membranes in water electrolysis for green hydrogen production

2024-11-14

Hydrogen is a promising energy source due to its high energy density and zero carbon emissions, making it a key element in the shift toward carbon neutrality. Traditional hydrogen production methods, like coal gasification and steam methane reforming, release carbon dioxide, undermining environmental goals. Electrochemical water splitting, which yields only hydrogen and oxygen, presents a cleaner alternative. While proton exchange membrane (PEM) and alkaline water electrolyzers (AWEs) are available, they face limitations in either cost or efficiency. PEM electrolyzers, for instance, rely on costly platinum group metals (PGMs) as catalysts, whereas ...

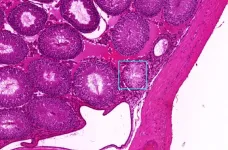

AI method can spot potential disease faster, better than humans

2024-11-14

PULLMAN, Wash. – A “deep learning” artificial intelligence model developed at Washington State University can identify pathology, or signs of disease, in images of animal and human tissue much faster, and often more accurately, than people.

The development, detailed in Scientific Reports, could dramatically speed up the pace of disease-related research. It also holds potential for improved medical diagnosis, such as detecting cancer from a biopsy image in a matter of minutes, a process that typically takes ...

A development by Graz University of Technology makes concreting more reliable, safer and more economical

2024-11-14

Concreting mistakes can be expensive. Concrete poured too quickly often leads to a lack of colour uniformity, irregularities in the structure and uneven surfaces. Particularly in the case of exposed concrete, expensive reworking using concrete cosmetics is then necessary, sometimes a wall may even have to be demolished. In addition, if the fresh concrete rises too quickly in the formwork, there is a certain risk potential for the workers, as this can cause the formwork to break. In their DigiCoPro project, Ralph Stöckl and ...

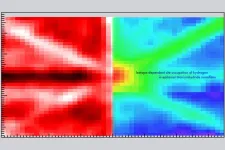

Pinpointing hydrogen isotopes in titanium hydride nanofilms

2024-11-14

Tokyo, Japan – Although it is the smallest and lightest atom, hydrogen can have a big impact by infiltrating other materials and affecting their properties, such as superconductivity and metal-insulator-transitions. Now, researchers from Japan have focused on finding an easy way to locate it in nanofilms.

In a study published recently in Nature Communications, researchers from the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo have reported a method for determining the location of hydrogen in nanofilms.

Because they are very small, hydrogen atoms can easily migrate into the framework of other materials. Titanium absorbs hydrogen to give titanium hydrides, making ...

Political abuse on X is a global, widespread, and cross-partisan phenomenon, suggests new study

2024-11-14

A new study suggests that political abuse is a key feature of political communication on social media platform, ‘X’, and whether on the political left or right, it is just as common to see politically engaged users abusing their political opponents, to a similar degree, and with little room for moderates.

While previous research into such online abuse has typically focused on the USA, the current study found that abuse followed a common ally-enemy structure across the nine countries for which there was available data: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Turkey, ...

Reintroduction of resistant frogs facilitates landscape-scale recovery in the presence of a lethal fungal disease

2024-11-14

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — A remote lakeshore deep inside Yosemite National Park teems with life: coyotes, snakes, birds, tadpoles, frogs. The frogs are at the heart of this scene, which a decade ago was much different. It was quiet — and not in a good way. The frogs that are so central to this ecosystem were absent, extirpated by a deadly fungal disease known as amphibian chytrid fungus.

Now, thanks to the consistent and focused efforts of researchers and conservationists to save, then reintroduce, mountain yellow-legged frogs to this and numerous other lakes in Yosemite, their populations are again thriving.

A ...

Scientists compile library for evaluating exoplanet water

2024-11-14

ITHACA, N.Y. – By probing chemical processes observed in the Earth’s hot mantle, Cornell scientists have started developing a library of basalt-based spectral signatures that not only will help reveal the composition of planets outside of our solar system but could demonstrate evidence of water on those exoplanets.

“When the Earth’s mantle melts, it produces basalts,” said Esteban Gazel, professor of engineering. Basalt, a gray-black volcanic rock found throughout the solar system, are key recorders of geologic history, he said.

“When the Martian mantle melted, it also produced basalts. The moon is mostly basaltic,” he said. “We’re ...