(Press-News.org) Mercury is extraordinarily toxic, but it becomes especially dangerous when transformed into methylmercury – a form so harmful that just a few billionths of a gram can cause severe and lasting neurological damage to a developing fetus. Unfortunately, methylmercury often makes its way into our bodies through seafood – but once it’s in our food and the environment, there’s no easy way to get rid of it.

Now, leveraging high-energy X-rays at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, researchers have identified an unexpected major player in methylmercury poisoning – a molecule called S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM).

The results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help researchers figure out new ways to address methylmercury poisoning.

“Nobody knew how mercury is methylated biologically,” said Riti Sarangi, a senior scientist in SSRL’s Structural Molecular Biologyprogram and co-author on the paper. “We need to understand that fundamental process before we can develop an effective methylmercury remediation strategy. This study is a step toward that.”

At issue in the new paper is a narrow but essential mystery concerning how methylmercury is produced. Scientists knew that most of the mercury we consume starts out as industrial emissions that make their way into bodies of water, where microbes convert it into methylmercury. That form concentrates in fish – and ultimately us – as it moves up the food web.

Still, researchers weren’t sure how microorganisms make methylmercury. A key confounding factor, Sarangi said, is that the protein system that converts mercury to methylmercury, called HgcAB, is present only in very small amounts in microbes, making it extremely difficult to gather and purify enough to study. It’s also extremely finicky: The slightest exposure to oxygen and light deactivates HgcAB.

In an effort spanning 10 years and collaborations across national laboratories and universities, University of Michigan professor Steve Ragsdale, his graduate student Katherine Rush, now an assistant professor at Auburn University, and postdoctoral associate Kaiyuan Zheng developed a new protocol to yield enough stable HgcAB to finally investigate how it transforms mercury into methylmercury.

“We’ve worked with a lot of very difficult proteins, but this one had everything you would not want to have in a protein if you wanted to purify it. It was very complicated,” Ragsdale said.

Once the team purified enough HgcAB, they transported the samples – cooled by liquid nitrogen and shielded from light – to SSRL for X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements. There, SSRL associate scientist Macon Abernathy used a method called extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy to study HgcAB.

“SSRL’s X-ray spectroscopy facilities are especially equipped to study biological samples and have powerful detector systems that can resolve the extremely weak signals of ultra dilute protein samples like these,” Sarangi said.

While previous studies hypothesized that the methyl group in question came from methyltetrahydrofolate, a common methyl donor in cellular reactions, the new study finds that it was donated by SAM instead. The researchers said that the results, which narrow in on the main actors in the production of methylmercury, could aid in the development of environmental remediation strategies.

“No one has tried it yet, but perhaps analogs of SAM could be developed that could address methylmercury in the environment,” Ragsdale said.

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology program is supported by the DOE Office of Science and the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

END

How microbes create the most toxic form of mercury

2024-11-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

‘Walk this Way’: FSU researchers’ model explains how ants create trails to multiple food sources

2024-11-15

It’s a common sight — ants marching in an orderly line over and around obstacles from their nest to a food source, guided by scent trails left by scouts marking the find. But what happens when those scouts find a comestible motherlode?

A team of Florida State University researchers led by Assistant Professor of Mathematics Bhargav Karamched has discovered that in a foraging ant’s search for food, it will leave pheromone trails connecting its colony to multiple food sources when they’re available, ...

A new CNIC study describes a mechanism whereby cells respond to mechanical signals from their surroundings

2024-11-15

To the casual eye, a memory foam mattress would appear to have no relationship to the behavior of cells and tissues. But an innovative study carried out at the Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid shows that viscoelasticity—the capacity of a material to be compressed and then recover its original form, like memory foam—is a little-explored property of biological tissues that is essential for correct cell function.

Study leader Dr. Jorge Alegre-Cebollada, who heads the Molecular Mechanics of the Cardiovascular System laboratory at the CNIC, explained that proper cell function requires ...

Study uncovers earliest evidence of humans using fire to shape the landscape of Tasmania

2024-11-15

Some of the first human beings to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, about 2,000 years earlier than previously thought.

A team of researchers from the UK and Australia analysed charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud to determine how Aboriginal Tasmanians shaped their surroundings. This is the earliest record of humans using fire to shape the Tasmanian environment.

Early human migrations from Africa to the southern part of the globe were well underway during the early part of the last ice age – humans reached northern ...

Researchers uncover Achilles heel of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

2024-11-15

Recent estimates indicate that deadly antibiotic-resistant infections will rapidly escalate over the next quarter century. More than 1 million people died from drug-resistant infections each year from 1990 to 2021, a recent study reported, with new projections surging to nearly 2 million deaths each year by 2050.

In an effort to counteract this public health crisis, scientists are looking for new solutions inside the intricate mechanics of bacterial infection. A study led by researchers at the University of California San Diego has discovered a vulnerability within strains of bacteria that are antibiotic resistant.

Working with labs at Arizona State University and the Universitat ...

Scientists uncover earliest evidence of fire use to manage Tasmanian landscape

2024-11-15

Some of the first humans to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, a new study from The Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Cambridge has found.

It is thought to be the earliest and most detailed record of humans using fire in the Tasmanian environment.

According to the researchers, early inhabitants of Tasmania were managing forests and grasslands by burning them to create open spaces, possibly for food procurement and cultural activities.

The team analysed traces of charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud that showed how Indigenous Tasmanians (Palawa) ...

Interpreting population mean treatment effects in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

2024-11-15

About The Study: Inferences about clinical impacts based on population-level mean treatment effects may be misleading, since even small between-group differences may reflect clinically important treatment benefits for individual patients. Results of this study suggest that clinical trials should explicitly describe the distributions of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire change at the patient level within treatment groups to support the clinical interpretation of their results.

Corresponding ...

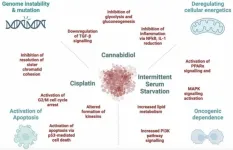

Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer: Synergy of therapies

2024-11-15

“This commentary will discuss what is known about such combinatorial treatments, including potential mechanisms and future protocols.”

BUFFALO, NY- November 15, 2024 – A new review was published in Volume 11 of Oncoscience on November 12, 2024, entitled, “Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer - synergy between DNA-damaging agents, cannabinoids, and intermittent serum starvation.”

As highlighted by the authors in the abstract of this review, chemotherapy is a common treatment for many cancers. However, it is often ineffective for long-term patient survival and ...

Stress makes mice’s memories less specific

2024-11-15

Stress is a double-edged sword when it comes to memory: stressful or otherwise emotional events are usually more memorable, but stress can also make it harder for us to retrieve memories. In PTSD and generalized anxiety disorder, overgeneralizing aversive memories results in an inability to discriminate between dangerous and safe stimuli. However, until now, it wasn’t clear whether stress played a role in memory generalization.

Now, neuroscientists report November 15 in the Cell Press journal Cell that acute stress prevents mice from forming specific memories. Instead, the stressed mice formed generalized memories, which are ...

Research finds no significant negative impact of repealing a Depression-era law allowing companies to pay workers with disabilities below minimum wage

2024-11-15

PHILADELPHIA—Debate continues to swirl nationally on the fate of a practice born of an 86-year-old federal statute allowing companies to pay workers with disabilities subminimum wages: anything below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, but for some roles as little as 25-cents-per-hour. Those in favor of repealing this statute highlight assumptions about reduced productivity along with the unfairness of this wage level—often used elsewhere to pay, for example, food service workers who typically make additional wages in tips. Those against repeal have voiced concerns that, without subminimum ...

Resilience index needed to keep us within planet’s ‘safe operating space’

2024-11-15

EMBARGOED: NOT FOR RELEASE UNTIL FRIDAY 15 NOVEMBER 2024 AT 11:00 ET (15:00 UK TIME).

Researchers are calling for a ‘resilience index’ to be used as an indicator of policy success instead of the current focus on GDP.

They say that GDP ignores the wider implications of development and provides no information on our ability to live within our planet’s ‘safe operating space’.

In a paper published today [15 November] in the journal One Earth, researchers from the University of Southampton, UCL ...