(Press-News.org) As an undergraduate student at Zhejiang University in eastern China, Greg Liu went with some of his classmates on a university-sponsored trip to tour a host of chemical industries within the area.

The tour gave students pursuing degrees in chemical engineering an opportunity to learn more about the manufacturing and production processes of chemicals within China at the time. Liu realized that day exactly what he wanted to do for a career – find ways to alleviate or stop the industry from polluting the environment.

“I realized that this was not going to be the sustainable way of our future. Pollution was everywhere, water, soil, road, you name it. Workers were in unbearable working conditions. I didn’t want to be in an environment like that, nor our future generations,” Liu said. “That basically drove me to think, ‘OK, I must pursue an advanced degree to change the way we work in the chemical industry.’”

Liu later came to the United States and earned his doctoral degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Now, his zeal to use his knowledge of chemical engineering to create a more sustainable world has led to him developing a revolutionary way to deal with arguably one of the world’s most pressing issues — plastic pollution.

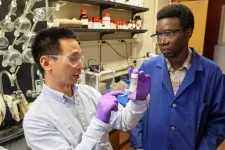

A long research project encompassing five or six years finally led to a breakthrough, with Liu, a professor within Virginia Tech’s Department of Chemistry housed in the College of Science, and his team of undergraduate and graduate students finding a way to convert certain plastics into soaps, detergents, lubricants, and other products. Liu has written an article about the process and the feasibility and commercialization of it that recently published in Nature Sustainability, a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

In simple terms, Liu’s system was two steps. It first involved using thermolysis, or breaking down a substance – in this case, plastic – by using heat. Plastic placed in a reactor built by Liu’s team and heated to between 650 and 750 degrees Fahrenheit broke down into chemical compounds, leaving a mixture of oil, gas, and residual solids. The key to this first step was breaking down the polypropylene and polyethylene molecules that make up plastic within a certain carbon range, and Liu and his team were able to accomplish this.

The residual solids left behind were minimal, and the gas could be captured and used as fuel. The oil, though, was the product of the most interest here.

During his research, Liu was able to functionalize, or change the chemistry, of the oil into molecules to be converted into soaps, detergents, lubricants, and other products.

“These materials are stable,” Liu said, holding up a vial of soap. “This vial of soap has been in my office for, I would say, a year already. … You could use it to wash your hands and dishes. We have used it to wash our lab glassware in the laboratory.”

<p>Your browser does not support iframes. Link to iframe content: <a href="https://open.spotify.com/embed/episode/0lbGVu7Eky5xH6XX2emY7s?utm_source=generator&theme=0">https://open.spotify.com/embed/episode/0lbGVu7Eky5xH6XX2emY7s?utm_source=generator&theme=0</a></p>

The process, which took less than a day, led to almost zero air pollution output, thus offering clues to a desperately needed solution to a global problem. According to the United Nation’s website, the world produces 430 million tons of plastic each year, with the equivalent of 2,000 garbage trucks full of plastic dumped into oceans, rivers, and lakes each day.

Plastic pollution leads to an increased choking of marine wildlife, the damaging of soils, the poisoning of groundwater, and the causing of negative human health impacts. In addition, there are greenhouse gas emissions released into the air during production.

The United Nations expects plastic pollution to triple by 2060 if no action is taken. Unfortunately, according to the United Nation's website, less than 9 percent of plastic actually gets recycled – though there is a reason for that, according to Amanda Morris, the head of the Virginia Tech’s Department of Chemistry.

“We make plastics to last from the perspective that many of them have to hold a liquid inside them that you don’t want coming out of a bottle. So they have to be relatively strong materials,” Morris said. “The bonds that hold the polymer together and give us that strength and give us the properties of the bottles that we use are also really hard to break, and so it’s just trying to come up with ways to do it in an energy efficient manner where you get clean product.

“The other thing is that those polymers can degrade into many different things. Are there ways that we can get it to one specific product that then could actually be used downstream again? I think those are some of the things that we’ve struggled with.”

Liu and his team have come up with a way to break those bonds, but now potentially comes the hard part – scaling up the system and making it a continuous one, while, more importantly, making it cost effective.

His is the plight of many researchers. They often find solutions to issues, but those solutions can come with hefty price tags, often resulting in the solutions remaining on the sidelines. Liu said industries have expressed interest in upscaling this process, but any effort, energy, and investment needs to result in profitability.

Liu said he is seeking help from the community to test a business model. This involves securing capital needed to build a reactor to run continuously in his lab, or perhaps creating a private offsite start-up company to test the ramping up of his process. Yes, soap can be created from a few pieces of plastic, but can tons of plastic generate soaps and detergents profitably?

“There will be a lot of demand on our end to further derisk the process,” Liu said. “We have to derisk it so they [businesses] can see real value out of it, and they can potentially adopt it.

“My estimate is in the hundreds of thousands of dollars range to test this. The good thing is that we’re training talented students and postdocs in this lab right now. They will be the ones who can potentially carry on this process in the future. But we definitely need more resources, especially funds, to build reactors and test the reactors.”

Back-end challenges aside, Morris remains optimistic about Liu’s findings and their future impacts. She welcomes opportunities to publicize his efforts tackling the plastics problem and discussing the chemistry department’s efforts in meeting this challenge as part of Virginia Tech’s Global Distinction ambitions.

“I think that any time that we can make our science accessible to the broader public, including our alumni and friends, it’s incredibly beneficial,” Morris said. “It’s beneficial for them to see the impact that we’re having not just as Hokies, but also that they can have by investing further in the Virginia Tech mission.

“The goal is really to take Greg’s technology, make modifications based on what we understand fundamentally about the process, and then make it even more energy efficient and more beneficial to industry. The other thing is that Greg’s technology is for a few polymer classes [with a recycle code of 2, 4, and 5], so can we apply that to other polymer classes? Are there ways where we can increase the reach of the technology? That has me excited as well.”

Liu doesn’t view himself as a pioneer, although, in this case, he truly is a pioneer of converting plastic waste to soap. Instead, he views himself as someone contributing a small piece to the solution of a global problem that requires everyone’s diligence. He said he welcomes more involvement from the scientific and industrial community.

In other words, science needs more collaboration on this problem. The stakes are too high without it.

“It’s no longer enough to be like, ‘Oh, I can play with my cool chemistry in the laboratory, and I can magically generate something out of it, and then I’m good enough,’” Liu said. “That is surely cool, but that isn’t the real solution to the pressing problem of plastic crisis.

“I hope, down the road, we find a solution, and I hope plastic is no longer a problem to worry about. I hope, in time, society will take care of all these waste materials. We can generate useful chemicals and materials from waste, and hopefully we can close the loop of carbon and plastics. That is my dream. I believe we can achieve it, but it’s going to take a while. With everyone’s will, we will solve it.”

END

Greg Liu is in his element using chemistry to tackle the plastics problem

Liu, a professor in the Department of Chemistry, has found a way to convert certain plastics into soaps and detergents, and now he is helping to explore business models that can profitably use his process on a much larger scale.

2024-11-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cocoa or green tea could protect you from the negative effects of fatty foods during mental stress - study

2024-11-18

University of Birmingham News Release

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL Monday 18th November 2024 8.00am UK/ 3.00am EST

Cocoa or green tea could protect you from the negative effects of fatty foods during mental stress - study

New research has found that a flavanol-rich cocoa drink can protect the body’s vasculature against stress even after eating high-fat food.

Food choices made during periods of stress can influence the effect of stress on cardiovascular health. For example, recent research from the University of Birmingham found that high-fat foods can negatively affect vascular function and oxygen delivery to the brain, meanwhile flavanol compounds found in abundance in cocoa ...

A new model to explore the epidermal renewal

2024-11-18

The mechanisms underlying skin renewal are still poorly understood. Interleukin-38 (IL-38), a protein involved in regulating inflammatory responses, could be a game changer. A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has observed it for the first time in the form of condensates in keratinocytes, the cells of the epidermis. The presence of IL-38 in these aggregates is enhanced close to the skin’s surface exposed to atmospheric oxygen. This process could be linked to the initiation of programmed ...

Study reveals significant global disparities in cancer care across different countries

2024-11-18

A recent analysis reveals striking disparities in the cost and availability of cancer drugs across different regions of the globe, with significant gaps between high- and low-income countries. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

The analysis, which drew on relevant published studies and reviews related to cancer and the availability of cancer treatments, predicts that there will be an estimated 28.4 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2040 alone. In the coming years, cancer incidence is expected to increase most significantly in low-income countries. Cancer mortality ...

Proactively screening diabetics for heart disease does not improve long-term mortality rates or reduce future cardiac events, new study finds

2024-11-18

While coronary heart disease and diabetes are often seen in the same patients, a diagnosis of diabetes does not necessarily mean that patients also have coronary heart disease, according to a new study from researchers at Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City.

The Intermountain study found that proactively screening patients with diabetes 1 and 2 for coronary heart disease who have not shown symptoms of heart problems does not improve long-term mortality rates, nor does it lower the chance of them ...

New model can help understand coexistence in nature

2024-11-18

Different species of seabirds can coexist on small, isolated islands despite eating the same kind of fish. A researcher at Uppsala University has been involved in developing a mathematical model that can be used to better understand how this ecosystem works.

“Our model shows that coexistence occurs naturally when species differ in their ability to catch fish and to efficiently fly long distances to the area where they catch fish,” says Claus Rüffler, Associate Professor of Animal Ecology at Uppsala University.

Seabirds can breed in very large colonies, sometimes consisting of several hundred thousand pairs. Ecologists working ...

National Poll: Some parents need support managing children's anger

2024-11-18

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Many parents are all too familiar with angry outbursts from their children, from sibling squabbles to protests over screen time limits.

But some parents may find it challenging to help their kids manage intense emotions. One in seven think their child gets angrier than peers of the same age and four in 10 say their child has experienced negative consequences when angry, a new national poll suggests.

Seven in 10 parents even think they sometimes set a bad example of handling anger themselves, according to the University of Michigan Health ...

Political shadows cast by the Antarctic curtain

2024-11-18

The scientific debate around the installation of a massive underwater curtain to protect Antarctic ice sheets from melting lacks its vital political perspective. A Kobe University research team argues that the serious questions around authority, sovereignty and security should be addressed proactively by the scientific community to avoid the protected seventh continent becoming the scene or object of international discord.

A January 2024 article in Nature put the spotlight on a bold idea originally proposed by Finnish researchers to save the West Antarctic ...

Scientists lead study on ‘spray on, wash off’ bandages for painful EB condition

2024-11-18

Research into new bandaging aims to ease the agony experienced by those living with genetic skin condition Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB), commonly referred to as 'butterfly skin'.

Scientists at Maynooth University in Ireland are leading research into whether ‘spray on, wash off’ bandages will be a viable alternative to those currently used, which can cause severe pain when applied and removed.

EB, which affects over 500,000 children and adults worldwide including 5,000 in the UK and 300 ...

A new discovery about pain signalling may contribute to better treatment of chronic pain

2024-11-18

When pain signals are passed along the nervous system, proteins called calcium channels play a key role. Researchers at Linköping University, Sweden, have now pinpointed the exact location of a specific calcium channel fine-tuning the strength of pain signals. This knowledge can be used to develop drugs for chronic pain that are more effective and have fewer side effects.

Pain sensations and other information are mainly conducted through our nervous system as electrical signals. Yet at decisive moments, this information is converted to biochemical signals, in the form of specific molecules. To develop future drugs ...

Migrating birds have stowaway passengers: invasive ticks could spread novel diseases around the world

2024-11-18

Ticks travel light, but they carry pathogens with them. When they parasitize migrating birds, these journeys can take them thousands of miles away from their usual geographic range. Historically, they haven’t been able to establish themselves, due to unsuitable climate conditions at the other end of their long journeys. But now, thanks to the climate crisis, it’s getting easier for ticks to survive and spread, potentially bringing novel tick-borne pathogens with them.

“If conditions become more hospitable for tropical tick species to establish themselves in areas where they would previously have been unsuccessful, then there is a chance they could bring new diseases ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tiny bubbles, big breakthrough: Cracking cancer’s “fortress”

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

How can you rescue a “kidnapped” robot? A new AI system helps the robot regain its sense of location in dynamic, ever-changing environments

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

[Press-News.org] Greg Liu is in his element using chemistry to tackle the plastics problemLiu, a professor in the Department of Chemistry, has found a way to convert certain plastics into soaps and detergents, and now he is helping to explore business models that can profitably use his process on a much larger scale.