(Press-News.org) Individual cells appear capable of learning, a behaviour once deemed exclusive to animals with brains and complex nervous systems, according to the findings of a new study led by researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The findings, published today in the journal Current Biology, could represent an important shift in how we view the fundamental units of life.

“Rather than following pre-programmed genetic instructions, cells are elevated to entities equipped with a very basic form of decision making based on learning from their environments,” says Jeremy Gunawardena, Associate Professor of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School, and co-author of the study.

The study looked at habituation, the process by which an organism gradually stops responding to a repeated stimulus. Its why humans stop noticing the ticking of a clock or become less distracted by flashing lights. This lowest form of learning has been studied extensively in animals with complex nervous systems.

Whether learning-like behaviours like habituation exist at cellular scale is a question that’s remained fraught with controversy. Early 20th-century experiments with the single-celled ciliate Stentor roeselii first shed light on behaviour that resembled learning, but the studies were overlooked and dismissed at the time. In the 1970s and 1980s, signs of habituation were found in other ciliates, and modern experiments have continued to add further weight to the theory.

“These creatures are so different from animals with brains. To learn would mean they use internal molecular networks that somehow perform functions similar to those carried out by networks of neurons in brains. Nobody knows how they are able to do this, so we thought it is a question that needed to be explored,” says Rosa Martinez, co-author of the study and researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona.

Cells rely on biochemical reactions as their means of processing information. For example, the addition or removal of a phosphate tag from the surface of a protein causes it to switch on or off. To track how cells process information, instead of working with cells in lab dishes, the researchers used computer simulations based on mathematical equations to monitor these reactions and decode the ‘language’ of the cell. This allowed them to see how the molecular interactions inside cells changed when exposed to the same stimulus over and over again.

Specifically, the study looked at two common molecular circuits – negative feedback loops and incoherent feedforward loops. In negative feedback, the output of a process inhibits its own production, like a thermostat shutting off a heater when a room reaches a certain temperature. In incoherent feedforward loops, a signal simultaneously activates both a process and its inhibitor, like a motion-activated light with a timer. After detecting movement, the light automatically switches off after a certain period of time.

The simulations suggest that cells use a combination of at least two of these molecular circuits to finetune their response to a stimulus and reproduce all the hallmark features of habituation seen in more complex forms of life. One of the key findings is a requirement for "timescale separation" in the behaviour of the molecular circuits, where some reactions happen much faster than others.

“We think this could be a type of ‘memory’ at the cellular level, enabling cells to both react immediately and influence a future response” explains Dr. Martinez.

The finding may also illuminate a longstanding debate between neuroscientists and cognitive researchers. For years, these two groups have had different takes on how habituation strength relates to the frequency or intensity of stimulation. Neuroscientists focus on observable behaviour, noting that organisms show stronger habituation with more frequent or less intense stimuli.

Cognitive scientists, however, insist on testing for the existence of internal changes and memory formation after habituation has taken place. When following their methodology, habituation seems stronger for less frequent or more intense stimuli.

The study shows that the behaviour of the models aligns with both views. During habituation, the response decreases more with more frequent or less intense stimuli, but after habituation, the response to a common stimulus is also stronger in these cases.

“Neuroscientists and cognitive scientists have been studying processes which are basically two sides of the same coin,” says Gunawardena. “We believe that single cells could emerge as a powerful tool to study the fundamentals of learning.”

The research deepens our understanding of how learning and memory operate at the most basic level of life. If single cells can “remember," it could also help explain how cancer cells develop resistance to chemotherapy or how bacteria become resistant to antibiotics — situations where cells seem to "learn" from their environment.

However, the predictions need to be confirmed with real-world biological data. The study used mathematical modelling to explore the concept of learning in cells because it let them test many different scenarios rapidly to see which ones are worth investigating further in real experiments.

The work could lay the foundation for experimental scientists to now design lab experiments and test these predictions.

“The moonshot in computational biology is to make life as programmable as a computer, but lab experiments can be costly and time-consuming,” says Dr. Martinez, who is based at the Barcelona Collaboratorium, a joint initiative between the CRG and EMBL Barcelona specifically designed to advance research based on mathematical modelling to address big questions in biology.

“Our approach can help us prioritise which experiments are most likely to yield valuable results, saving time and resources and leading to new breakthroughs,” she adds. “We think it can be useful to address many other fundamental questions.”

END

Can cells ‘learn’ like brains?

Simulations explain how tiny single-celled creatures may exhibit forms of learning deemed exclusive to more complex life forms

2024-11-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How cells get used to the familiar

2024-11-19

A dog learns to sit on command, a person hears and eventually tunes out the hum of a washing machine while reading … The capacity to learn and adapt is central to evolution and, indeed, survival.

Habituation — adaptation’s less-glamorous sibling — involves the lessening response to a stimulus after repeated exposure. Think the need for a third espresso to maintain the same level of concentration you once achieved with a single shot.

Up until recently, habituation — a simple form of learning — was deemed ...

Seemingly “broken” genes in coronaviruses may be essential for viral survival

2024-11-19

Viruses are lean, mean, infection machines. Their genomes are tiny, usually limited to a handful of absolutely essential genes, and they shed extra genomic deadweight extremely fast.

Usually.

Coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), appear at first glance to be an exception. They have some extra “accessory” genes in addition to the usual minimal viral set, and scientists don’t know what most of them do. Scientists believe these extra genes must be doing something important, though, or they would be rapidly lost as the viruses evolved.

Now, University of Utah Health researchers have found that some of these viral genes have stuck around ...

Improving hurricane modeling with physics-informed machine learning

2024-11-19

WASHINGTON, Nov. 19, 2024 – Hurricanes, or tropical cyclones, can be devastating natural disasters, leveling entire cities and claiming hundreds or thousands of lives. A key aspect of their destructive potential is their unpredictability. Hurricanes are complex weather phenomena, and how strong one will be or where it will make landfall is difficult to estimate.

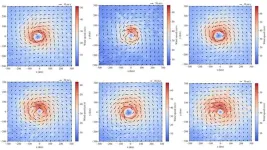

In a paper published this week in Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, a pair of researchers from the City University of Hong Kong employed machine learning to more accurately model the boundary layer wind field of tropical cyclones.

In atmospheric science, the boundary layer ...

Seed slippage: Champati cha-cha

2024-11-19

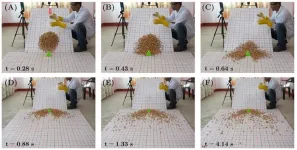

WASHINGTON, Nov 19, 2024 – Champatis, the seeds of the Lapsi tree, are valued in Nepal for their medical, economic, social, and cultural significance. They are also popular among children as simple playthings. But for a group of physicists, these unique seeds—and the way they bounce and roll down slopes—could help them better understand landslides and avalanches, leading to research that could save lives.

In a study published this week in Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, a team ...

Hospitalization following outpatient diagnosis of RSV in adults

2024-11-19

About The Study: In this cohort study of adults with outpatient medically attended-respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections from 3 large deidentified U.S. databases across 6 RSV seasons, approximately 1 in 20 adults experienced all-cause hospitalization within 28 days. The results of this study highlight the public health need for RSV prevention and treatment.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Joshua T. Swan, PharmD, MPH, email swan.joshua@gmail.com.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media ...

Beyond backlash: how feeling threatened by diversity can trigger positive change

2024-11-19

In recent years, employers across North America have introduced or boosted equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) programs in hopes of creating a more diverse and inclusive workplace culture.

But studies have shown that fostering diversity can come with a steep cost, as employees from dominant groups often felt threatened, leading to a backlash against the very groups the employers are seeking to support.

But could those feelings of threat also lead to learning and change, and eventually allyship? ...

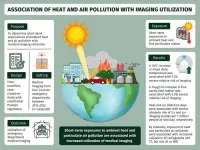

Climate change exposure associated with increased emergency imaging

2024-11-19

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Using data collected over a 10-year period from four emergency departments, researchers at the University of Toronto found that short-term exposure to ambient heat and air pollution levels was associated with increased utilization of X-rays and computed tomography (CT). Results of the study were published today in Radiology, a journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

“Extreme climate exposures are associated with higher demand for health care including emergency department visits,” ...

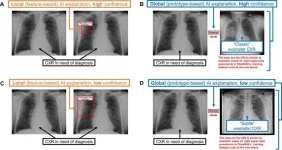

Incorrect AI advice influences diagnostic decisions

2024-11-19

OAK BROOK, Ill. – When making diagnostic decisions, radiologists and other physicians may rely too much on artificial intelligence (AI) when it points out a specific area of interest in an X-ray, according to a study published today in Radiology, a journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

“As of 2022, 190 radiology AI software programs were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration,” said one of the study’s senior authors, Paul H. Yi, M.D., director of intelligent imaging informatics and associate member in ...

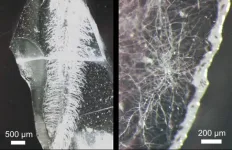

Building roots in glass, a bio-inspired approach to creating 3D microvascular networks using plants and fungi

2024-11-19

Fukuoka, Japan— Microfluidic technology has become increasingly important in many scientific fields such as regenerative medicine, microelectronics, and environmental science. However, conventional microfabrication techniques face limitations in scale and in the construction of complex networks. These hurdles are compounded when it comes to building more intricate 3D microfluidic networks.

Now, researchers from Kyushu University have developed a new and convenient technique for building such complex 3D microfluidic networks. Their tool? Plants and fungi. The team developed a ‘soil’ medium using nanoparticles of glass (silica) and a cellulose ...

Spinning fusion fuel for efficiency

2024-11-19

A different mix of fuels with enhanced properties could overcome some of the major barriers to making fusion a more practical energy source, according to a new study.

The proposed approach would still use deuterium and tritium, which are generally accepted as the most promising pair of fuels for fusion energy production. However, the quantum properties of the fuel would be adjusted for peak efficiency using an existing process known as spin polarization. In addition to spin polarizing half the fuels, the percentage of deuterium would be increased from the usual amount of roughly 60% or more.

Models created by scientists at the U.S. Department ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Can cells ‘learn’ like brains?Simulations explain how tiny single-celled creatures may exhibit forms of learning deemed exclusive to more complex life forms