https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1r5eJr78OdIYV0la1pBvRx-ksu9hsNqcw?usp=sharing

Post-embargo link to release:

https://www.washington.edu/news/2024/11/21/whale-ship-collisions/

FROM: James Urton

University of Washington

206-543-2580

jurton@uw.edu

(Note: researcher contact information at the end)

Embargoed by Science

For public release at 2 p.m. U.S. Eastern Standard Time (11 a.m. Pacific Standard Time) on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024

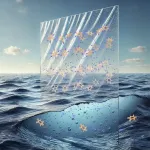

Fewer than 7% of global hotspots for whale-ship collisions have protection measures in place

According to the fossil record, cetaceans — whales, dolphins and their relatives — evolved from four-legged land mammals that returned to the oceans beginning some 50 million years ago. Today, their descendants are threatened by a different land-based mammal that has also returned to the sea: humans.

Thousands of whales are injured or killed each year after being struck by ships, particularly the large container vessels that ferry 80% of the world’s traded goods across the oceans. Collisions are the leading cause of death worldwide for large whale species. Yet global data on ship strikes of whales are hard to come by — impeding efforts to protect vulnerable whale species. A new study led by the University of Washington has for the first time quantified the risk for whale-ship collisions worldwide for four geographically widespread ocean giants that are threatened by shipping: blue, fin, humpback and sperm whales.

In the paper, published online Nov. 21 in Science, researchers report that global shipping traffic overlaps with about 92% of these whale species’ ranges.

“This translates to ships traveling thousands of times the distance to the moon and back within these species’ ranges each and every year, and this problem is only projected to increase as global trade grows in the coming decades,” said senior author Briana Abrahms, a UW assistant professor of biology and researcher with the Center for Ecosystem Sentinels.

“Whale-ship collisions have typically only been studied at a local or regional level — like off the east and west coasts of the continental U.S., and patterns of risk remain unknown for large areas,” said lead author Anna Nisi, a UW postdoctoral researcher in the Center for Ecosystem Sentinels. “Our study is an attempt to fill those knowledge gaps and understand the risk of ship strikes on a global level. It’s important to understand where these collisions are likely to occur because there are some really simple interventions that can substantially reduce collision risk.”

The team found that only about 7% of areas at highest risk for whale-ship collisions have any measures in place to protect whales from this threat. These measures include speed reductions, both mandatory and voluntary, for ships crossing waters that overlap with whale migration or feeding areas.

“As much as we found cause for concern, we also found some big silver linings,” said Abrahms. “For example, implementing management measures across only an additional 2.6% of the ocean’s surface would protect all of the highest-risk collision hotspots we identified.”

“Trade-offs between industrial and conservation outcomes are not usually this optimal,” said co-author Heather Welch, a research scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Oftentimes industrial activities must be greatly limited to achieve conservation goals, or vice versa. In this case, there is a potentially large conservation benefit to whales for not much cost to the shipping industry.”

Those highest-risk areas for the four while species included in the study lie largely along coastal areas in the Mediterranean, portions of the Americas, southern Africa and parts of Asia.

The international team behind the study, which includes researchers across five continents, looked at the waters where these four whale species live, feed and migrate by pooling data from disparate sources — including government surveys, sightings by members of the public, tagging studies and even whaling records. The team collected some 435,000 unique whale sightings. They then combined this novel database with information on the courses of 176,000 cargo vessels from 2017 to 2022 — tracked by each ship’s automatic identification system and processed using an algorithm from Global Fishing Watch — to identify where whales and ships are most likely to meet.

The study uncovered regions already known to be high-risk areas for ship strikes: North America’s Pacific coast, Panama, the Arabian Sea, Sri Lanka, the Canary Islands and the Mediterranean Sea. But it also identified understudied regions at high risk for whale-ship collisions, including southern Africa; South America along the coasts of Brazil, Chile, Peru and Ecuador; the Azores; and East Asia off the coasts of China, Japan and South Korea.

The team found that mandatory measures to reduce whale-ship collisions were very rare, overlapping just 0.54% of blue whale hotspots and 0.27% of humpback hotspots, and not overlapping any fin or sperm whale hotspots. Though many collision hotspots fell within marine protected areas, these preserves often lack speed limits for vessels, as they were largely established to curb fishing and industrial pollution.

For all four species the vast majority of hotpots for whale-ship strikes — more than 95% — hugged coastlines, falling within a nation’s exclusive economic zone. That means that each country could implement its own protection measures in coordination with the U.N.’s International Maritime Organization.

“From the standpoint of conservation, the fact that most high-risk areas lie within exclusive economic zones is actually encouraging,” said Nisi. “It means individual countries have the ability to protect the riskiest areas.”

Of the limited measures now in place, most are along the Pacific coast of North America and in the Mediterranean Sea. In addition to speed reduction, other options to reduce whale-ship strikes include changing vessel routings away from where whales are located, or creating alert systems to notify authorities and mariners when whales are nearby.

“Lowering vessel speed in hotspots also carries additional benefits, such as reducing underwater noise pollution, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and cutting air pollution, which helps people living in coastal areas,” said Nisi.

The authors hope their global study could spur local or regional research to map out the hotspot zones in finer detail, inform advocacy efforts and consider the impact of climate change, which will change both whale and ship distributions as sea ice melts and ecosystems shift.

“Protecting whales from the impact of ship strikes is a huge global challenge. We’ve seen the benefits of slowing ships down at local scales through programs like ‘Blue Whales Blue Skies’ in California. Scaling up such programs will require a concerted effort by conservation organizations, governments and shipping companies,” said co-author Jono Wilson, director of ocean science at the California Chapter of The Nature Conservancy, which helped identify the need for this study and secured its funding. “Whales play a critical role in marine ecosystems. Through this study we have measurable insights into ship-collision hotspots and risk and where we need to focus to make the most impact.”

Co-authors on the study are Stephanie Brodie, a research scientist with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia; research scientists Callie Leiphardt and Rachel Rhodes, and professor Douglas McCauley, all at the University of California, Santa Barbara; Elliott Hazen, research ecologist with NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center; Jessica Redfern, associate vice president, Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, New England Aquarium; the UW’s Trevor Branch, professor of aquatic and fishery sciences, and Sue Moore, a research scientist with the Center for Ecosystem Sentinels; André Barreto, professor at the Universidade do Vale do Itajaí in Brazil; senior research biologist John Calambokidis with the Cascadia Research Collective; data scientist Tyler Clavelle, chief scientist David Kroodsma and senior manager Tim White with Global Fishing Watch; research scientists Lauren Dares and Chloe Robinson with Ocean Wise; Asha de Vos with Oceanswell in Sri Lanka and the University of Western Australia; Shane Gero with Carleton University; biologist Jennifer Jackson with the British Antarctic Survey; Robert Kenney, emeritus research scientist with the University of Rhode Island; Russell Leaper with the International Fund for Animal Welfare; Ekaterina Ovsyanikova at the University of Queensland; and Simone Panigada with the Tethys Research Institute in Italy.

The research was funded by The Nature Conservancy, NOAA, the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, the National Marine Fisheries Service, Oceankind, Bloomberg Philanthropy, Heritage Expeditions, Ocean Park Hong Kong, National Geographic, NEID Global and the Schmidt Foundation.

###

For more information, contact Nisi at anisi@uw.edu and Abrahms at abrahms@uw.edu.

REFERENCE:

Nisi AC et al. "Ship collision risk threatens whales across the world’s oceans." Science. Nov. 22, 2024 print edition. DOI: 10.1126/science.adp1950

NOTE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON NEWS OFFICE:

In accordance with Science policy, the University of Washington news office is prohibited from sharing advance copies of this study. Advance copies of the paper may only be obtained by registered reporters via the Science Press Package, SciPak: https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak/

For reporters having difficulties accessing the paper from the press package, please contact scipak@aaas.org.

END