(Press-News.org) Just days before his fourth birthday, Santiago was diagnosed with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), the most common cancer in children.

He began chemotherapy the next day, and the outlook was promising – disease-free survival rates for B-ALL are among the highest for paediatric cancers, at 80 to 85 per cent. However, limited progress has been made over the last 15 years, and relapsed B-ALL remains a leading cause of cancer death among children.

Seeking to explore all options, Santiago’s parents enrolled him in a Children’s Oncology Group clinical trial led by scientists at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and Seattle Children’s Hospital. The trial, which included over two hundred sites across four countries, combined standard chemotherapy with two cycles of blinatumomab, an immunotherapy already used for children with relapsed B-ALL.

Early study results were so promising that the trial closed early, with findings published in the New England Journal of Medicine showing a striking 61 per cent reduction in the risk of B-ALL relapse or death for those who received both chemotherapy and blinatumomab.

“These breakthrough data showing a significant improvement in disease-free survival are set to bring a tremendous clinical benefit to nearly all children with newly diagnosed B-ALL,” says study co-lead Dr. Sumit Gupta, Oncologist and Associate Scientist in the Child Health Evaluative Sciences program at SickKids. “This is changing the standard of care for children with B-ALL around the world.”

Reducing relapse – and side effects

Before he joined the trial, Santiago received a combination therapy of steroids and chemotherapy, already personalized based on a genetic analysis of his leukemia cells showing which medications would be most effective for him.

“We knew the treatment was necessary, but the weight gain and loss of independence from the steroids were heartbreaking to watch,” says Beatriz, Santiago’s mother. “The first round of blinatumomab had its own side effects, but it was nothing compared to his previous treatment and it gave him so much more freedom to be a regular kid.”

Unlike chemotherapy, immunotherapies like blinatumomab use the body’s own immune system to fight cancer by teaching the immune system to target cancer cells. For children like Santiago with an average risk of relapse, the study showed that after three years, the disease-free survival rate increased to 97.5 per cent, compared to 90 per cent with chemotherapy alone. For children with a higher risk of relapse, receiving blinatumomab in addition to chemotherapy increased the disease-free survival rate from 85 per cent to over 94 per cent.

“These findings underscore the progress made with blinatumomab in preventing relapse and support its role as a critical addition to current therapeutic strategies,” says study co-lead Dr. Rachel Rau, paediatric hematologist-oncologist at Seattle Children's Hospital and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington.

A new era of childhood cancer treatment

The findings published today included 1,440 children from Canada, the U.S., Australia and New Zealand, and the results mark a significant milestone in the fight against childhood cancer. As a member of the Children’s Oncology Group, SickKids is working with more than 11,000 experts worldwide, to advance over 100 active clinical-translational trials at any given time. Of these active trials, those for children with B-ALL are being paused to introduce blinatumomab into their study designs as well.

“This new combination treatment is set to become the new standard of care for these patients, potentially saving many lives and reducing the fear and health impacts associated with relapse,” says Sumit, who is also an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto. “We are now designing the next generation of studies to see whether we can safely remove some of the chemotherapy that currently makes up standard treatment, while maintaining these outstanding success rates. It’s an incredibly exciting time to be in this field as we start to try to decrease the short and long-term side effects associated with treatment.”

Nine months after his first diagnosis, Santiago is excited to finally start school in the new year, trading in his shark backpack for a backpack he chose before his diagnosis. He will continue to take a low-intensity chemotherapy regimen intended to help prevent leukemia from returning, but his family is excited to start this new chapter together.

“This is Santiago’s journey. My job is to hold his hand and help make sure he gets the best care possible,” says Beatriz.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and St. Baldrick’s Foundation.

END

Global clinical trial shows improved survival rates for common childhood leukemia

2024-12-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

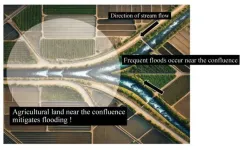

Agricultural land near where rivers meet can mitigate floods

2024-12-07

Tokyo, Japan – Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University showed that agricultural land preserved around river confluences can help mitigate floods. They make a case for Eco-DRR, an approach that uses existing environmental resources to improve resilience against flooding. Statistical analysis showed that municipalities with agricultural land in areas with high water storage potential suffered fewer floods, with stronger correlation when agricultural land was situated near river confluences. The team hope their findings inform effective land usage.

Climate change has brought ...

Hybrid theory offers new way to model disturbed complex systems

2024-12-06

In fields ranging from immunology and ecology to economics and thermodynamics, multi-scale complex systems are ubiquitous. They are also notoriously difficult to model. Conventional approaches take either a bottom-up or top-down approach. But in disturbed systems, such as a post-fire forest ecosystem or a society in a pandemic, these unidirectional models can’t capture the interactions between the small-scale behaviors and the system-level properties. SFI External Professor John Harte (UC Berkeley) and his collaborators have worked to resolve this challenge by building a hybrid method that links bottom-up behaviors and top-down causation in a single theory.

Harte et ...

MRI could be key to understanding the impact a gluten free diet has on people with coeliac disease

2024-12-06

Experts have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to better understand the impact a gluten free diet has on people with coeliac disease, which could be the first step towards finding new ways of treating the condition.

The MARCO study – MAgnetic Resonance Imaging in COliac disease – which is published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), was led by experts from the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham, alongside colleagues at the Quadram Institute.

Coeliac disease is a chronic condition affecting around one person in every 100 in the general population. When people with coeliac ...

New model for replication of BKPyV virus, a major cause of kidney transplant failure

2024-12-06

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – BK polyomavirus, or BKPyV, is a major cause of kidney transplant failure. There are no effective drugs to treat BKPyV. Research at the University of Alabama at Birmingham reveals new aspects of BKPyV replication, offering possible drug targets to protect transplanted kidneys.

To better understand BKPyV replication and ways to prevent it, researchers in the UAB Department of Microbiology have published a single-cell analysis of BKPyV infection in primary kidney cells. Their findings contradict a long-held understanding of the molecular events required for BKPyV ...

Scientists urged to pull the plug on ‘bathtub modeling’ of flood risk

2024-12-06

Irvine, Calif., Dec. 6, 2024 — Recent decades have seen a rapid surge in damages and disruptions caused by flooding. In a commentary article published today in the American Geophysical Union journal Earth’s Future, researchers at the University of California, Irvine and the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom – the latter also executives of U.K. flood risk intelligence firm Fathom – call on scientists to more accurately model these risks and caution against overly dramatized reporting of future risks in the news media.

In the paper, the researchers urge the climate science community to turn ...

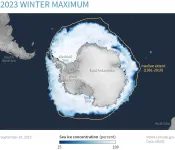

Record-low Antarctic sea ice can be explained and forecast months out by patterns in winds

2024-12-06

Amid all the changes in Earth’s climate, sea ice in the stormy Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica was, for a long time, an odd exception. The maximum winter sea ice cover remained steady or even increased slightly from the late 1970s through 2015, despite rising global temperatures.

That began to change in 2016. Several years of decline led to an all-time record low in 2023, more than five standard deviations below the average from the satellite record. The area of sea ice was 2.2 million square kilometers below the average from ...

UTIA team wins grant to advance AI education and career preparation

2024-12-06

Future farmers and leaders in agriculture need to understand and implement technologies that use artificial intelligence. A team of University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture faculty are working toward creating new curriculum to train the next generation of agriculture students.

Led by Hao Gan, assistant professor in the Department of Biosystems Engineering and Soil Science, the team won a four-year grant for $741,102 from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The project, “Development of a Smart Agricultural Experiential Learning Program for Youth,” will create hands-on curriculum about using drones, ground robots, computer ...

Magnetically controlled kirigami surfaces move objects: no grasping needed

2024-12-06

Researchers have developed a novel device that couples magnetic fields and kirigami design principles to remotely control the movement of a flexible dimpled surface, allowing it to manipulate objects without actually grasping them – making it useful for lifting and moving items such as fragile objects, gels or liquids. The technology has potential for use in confined spaces, where robotic arms or similar tools aren’t an option.

“We were trying to address two challenges here,” says Jie Yin, co-corresponding ...

Close encounters between distant DNA regions cause bursts of gene activity

2024-12-06

Fukuoka, Japan – Researchers at Kyushu University have revealed how spatial distance between specific regions of DNA is linked to bursts of gene activity. Using advanced cell imaging techniques and computer modeling, the researchers showed that the folding and movement of DNA, as well as the accumulation of certain proteins, changes depending on whether a gene is active or inactive. The study, published on December 6 in Science Advances, sheds insight into the complicated world of gene expression and could lead to new therapeutic techniques for diseases caused by improper regulation of gene expression.

Gene expression is a fundamental process that occurs within ...

High heat is preferentially killing the young, not the old, new research finds

2024-12-06

Many recent studies assume that elderly people are at particular risk of dying from extreme heat as the planet warms. A new study of mortality in Mexico turns this assumption on its head: it shows that 75% of heat-related deaths are occurring among people under 35―a large percentage of them ages 18 to 35, or the very group that one might expect to be most resistant to heat.

“It’s a surprise. These are physiologically the most robust people in the population,” said study coauthor Jeffrey Shrader of the Center for Environmental Economics and Policy, an affiliate of Columbia University’s Climate School. “I would love to know ...