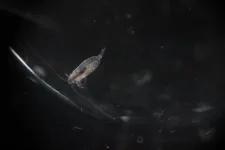

(Press-News.org) A Dartmouth-led study proposes a new method for recruiting trillions of microscopic sea creatures called zooplankton in the fight against climate change by converting carbon into food the animals would eat, digest, and send deep into the ocean as carbon-filled feces.

The technique harnesses the animals' ravenous appetites to essentially accelerate the ocean's natural cycle for removing carbon from the atmosphere, which is known as the biological pump, according to the paper in Nature Scientific Reports.

It begins with spraying clay dust on the surface of the ocean at the end of algae blooms. These blooms can grow to cover hundreds of square miles and remove about 150 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year, converting it into organic carbon particulates. But once the bloom dies, marine bacteria devour the particulates, releasing most of the captured carbon back into the atmosphere.

The researchers found that the clay dust attaches to carbon particulates before they re-enter the atmosphere, redirecting them into the marine food chain as tiny sticky pellets the ravenous zooplankton consume and later excrete at lower depths.

"Normally, only a small fraction of the carbon captured at the surface makes it into the deep ocean for long-term storage," says Mukul Sharma, the study's corresponding author and a professor of earth sciences. Sharma also presented the findings Dec. 10 at the American Geophysical Union annual conference in Washington, D.C.

"The novelty of our method is using clay to make the biological pump more efficient—the zooplankton generate clay-laden poops that sink faster," says Sharma, who received a Guggenheim Award in 2020 to pursue the project.

"This particulate material is what these little guys are designed to eat. Our experiments showed they cannot tell if it's clay and phytoplankton or only phytoplankton—they just eat it," he says. "And when they poop it out, they are hundreds of meters below the surface and the carbon is, too."

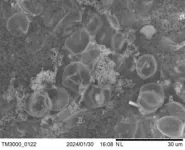

The team conducted laboratory experiments on water collected from the Gulf of Maine during a 2023 algae bloom. They found that when clay attaches to the organic carbon released when a bloom dies, it prompts marine bacteria to produce a kind of glue that causes the clay and organic carbon to form little balls called flocs.

The flocs become part of the daily smorgasbord of particulates that zooplankton gorge on, the researchers report. Once digested, the flocs embedded in the animals' feces sinks, potentially burying the carbon at depths where it can be stored for millennia. The uneaten clay-carbon balls also sink, increasing in size as more organic carbon, as well as dead and dying phytoplankton, stick to them on the way down, the study found.

In the team's experiments, clay dust captured as much as 50% of the carbon released by dead phytoplankton before it could become airborne. They also found that adding clay increased the concentration of sticky organic particles—which would collect more carbon as they sink—by 10 times. At the same time, the populations of bacteria that instigate the release of carbon back into the atmosphere fell sharply in seawater treated with clay, the researchers report.

In the ocean, the flocs become an essential part of the biological pump called marine snow, Sharma says. Marine snow is the constant shower of corpses, minerals, and other organic matter that fall from the surface, bringing food and nutrients to the deeper ocean.

"We're creating marine snow that can bury carbon at a much greater speed by specifically attaching to a mixture of clay minerals," Sharma says.

Zooplankton accelerate that process with their voracious appetites and incredible daily sojourn known as the diel vertical migration. Under cover of darkness, the animals—each measuring about three-hundredths of an inch—rise hundreds, and even thousands, of feet from the deep in one immense motion to feed in the nutrient-rich water near the surface. The scale is akin to an entire town walking hundreds of miles every night to their favorite restaurant.

When day breaks, the animals return to deeper water with the flocs inside them where they are deposited as feces. This expedited process, known as active transport, is another key aspect of the ocean's biological pump that shaves days off the time it takes carbon to reach lower depths by sinking.

Earlier this year, study co-author Manasi Desai presented a project conducted with Sharma and fellow co-author David Fields, a senior research scientist and zooplankton ecologist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Maine, showing that the clay flocs zooplankton eat and expel do indeed sink faster. Desai, a former technician in Sharma's lab, is now a technician in the Fields lab.

Sharma plans to field-test the method by spraying clay on phytoplankton blooms off the coast of Southern California using a crop-dusting airplane. He hopes that sensors placed at various depths offshore will capture how different species of zooplankton consume the clay-carbon flocs so that the research team can better gauge the optimal timing and locations to deploy this method—and exactly how much carbon it's confining to the deep.

"It is very important to find the right oceanographic setting to do this work. You cannot go around willy-nilly dumping clay everywhere," Sharma says. "We need to understand the efficiency first at different depths so we can understand the best places to initiate this process before we put it to work. We are not there yet—we are at the beginning."

In addition to Desai and Fields, Sharma worked with the study's first authors Diksha Sharma, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab who is now a Marie Curie Fellow at Sorbonne University in Paris, and Vignesh Menon, who received his master’s degree from Dartmouth this year and is now a PhD student at Gothenburg University in Sweden.

Additional study authors include George O'Toole, professor of microbiology and immunology in Dartmouth's Geisel School of Medicine, who oversaw the culturing and genetic analysis of bacteria in the seawater samples; Danielle Niu, who received her doctorate in earth sciences from Dartmouth and is now an assistant clinical professor at the University of Maryland; Eleanor Bates '20, now a PhD student at the University of Hawaii at Manoa; Annie Kandel, a former technician in Sharma's lab; and Erik Zinser, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Tennessee focusing on marine bacteria.

###

The study's first authors are Diksha Sharma, a postdoctoral researcher in the Sharma lab who is now a Marie Curie Fellow at Sorbonne University in Paris, and Vignesh Menon, who received his master’s degree from Dartmouth this year and is now a PhD student at Gothenburg University in Sweden.

Additional authors include George O'Toole, professor of microbiology and immunology in the Geisel School of Medicine, who oversaw the culturing and genetic analysis of bacteria in the seawater samples; Danielle Niu, who received her doctorate in earth sciences from Dartmouth and is now an assistant clinical professor at the University of Maryland; Eleanor Bates '20, now a PhD student at the University of Hawaii at Manoa; Annie Kandel, a former technician in Sharma's lab; and Erik Zinser, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Tennessee focusing on marine bacteria.

END

Tiny poops in the ocean may help solve the carbon problem

A Dartmouth-led study turns CO2 into food that zooplankton expel into the deep sea.

2024-12-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study offers insight into chloroplast evolution

2024-12-10

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — One of the most momentous events in the history of life involved endosymbiosis — a process by which one organism engulfed another and, instead of ingesting it, incorporated its DNA and functions into itself. Scientific consensus is that this happened twice over the course of evolution, resulting in the energy-generating organelles known as mitochondria and, much later, their photosynthetic counterparts, the plastids.

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications explores the origin of chloroplasts, the plastids that allow plants ...

Advancing the synthesis of two-dimensional gold monolayers

2024-12-10

Nanostructured two-dimensional gold monolayers offer possibilities in catalysis, electronics, and nanotechnology.

Researchers have created nearly freestanding nanostructured two-dimensional (2D) gold monolayers, an impressive feat of nanomaterial engineering that could open up new avenues in catalysis, electronics, and energy conversion.

Gold is an inert metal which typically forms a solid three-dimensional (3D) structure. However, in its 2D form, it can unlock extraordinary properties, such as unique electronic behaviors, enhanced surface reactivity, and immense potential for revolutionary applications in catalysis ...

Human disruption is driving ‘winner’ and ‘loser’ tree species shifts across Brazilian forests

2024-12-10

Fast-growing and small-seeded tree species are dominating Brazilian forests in regions with high levels of deforestation and degradation, a new study shows.

This has potential implications for the ecosystem services these forests provide, including the ability of these ‘disturbed’ forests to absorb and store carbon. This is because these “winning” species grow fast but die young, as their stems and branches are far less dense than the slow growing tree species they replace.

Wildlife species adapted to consuming and dispersing the large seeds of tree species that ...

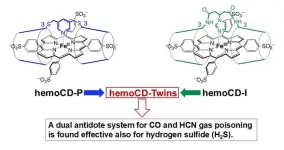

A novel heme-model compound that treats lethal gas poisoning

2024-12-10

You may not be familiar with hydrogen sulfide, a colorless gas that smells like rotten eggs, and is produced naturally from decaying matter. However, this gas is lethal to breathe in, and hydrogen sulfide present in high concentrations can cause death very rapidly. Its relative density is also greater than air, causing it to accumulate at lower altitudes and posing an enormous threat to workers at sites, such as manholes, sewage systems and mining operations.

Why is hydrogen sulfide so dangerous? It binds strongly to the heme-containing cytochrome c oxidase ...

Shape-changing device helps visually impaired people perform location task as well as sighted people - EMBARGO: Tuesday 10 December (10:00 UK time)

2024-12-10

IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON PRESS RELEASE

Under STRICT EMBARGO until:

10 December 2024

10:00 UK TIME / 05:00 ET

Peer-reviewed / Observational study / People

Trial shows no significant difference in performance between visually impaired participants using new device and sighted participants using only natural vision.

Participants performed significantly better using new device than with currently available vibration technology.

The new device is believed to be the most advanced navigation tech of ...

AI predicts that most of the world will see temperatures rise to 3°C much faster than previously expected

2024-12-10

Three leading climate scientists have combined insights from 10 global climate models and, with the help of artificial intelligence (AI), conclude that regional warming thresholds are likely to be reached faster than previously estimated.

The study, published in Environmental Research Letters by IOP Publishing, projects that most land regions as defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will likely surpass the critical 1.5°C threshold by 2040 or earlier. Similarly, several regions are on track to exceed the 3.0°C threshold ...

Second round of FRONTIERS Science Journalism Residency Program awards grants to ten journalists

2024-12-10

The FRONTIERS Science Journalism in Residency Programme has selected ten science journalists to participate in its second round of residencies. The chosen candidates—Marta Abbà, Rina Caballar, Danielle Fleming, Will Grimond, Giorgia Guglielmi, Suvi Jaakkola, Tim Kalvelage, Thomas Reintjes, Senne Starckx, and Meera Subramanian—will spend three to five months in residency at European research institutions, working on their journalistic projects.

The residencies, hosted by institutions in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and the United Kingdom, offer a unique opportunity ...

The inequity of wildfire rescue resources in California

2024-12-10

AUSTIN, TX, December 10, 2024 – Wildfires in California are intensifying due to warmer temperatures and dry vegetation – putting more residents at risk of experiencing costly damages or losing their homes. Marginalized populations (lower income, elderly, and the disabled) often suffer the most and, according to a new study, may receive less economic and emergency assistance compared to wealthy residents.

A detailed analysis of more than 500 California wildfire incidents from 2015 to 2022 by University at Buffalo scientists shows that disaster recovery resources in California favor people living in wealthy communities over disadvantaged ...

Aerosol pollutants from cooking may last longer in the atmosphere – new study

2024-12-10

New insights into the behaviour of aerosols from cooking emissions and sea spray reveal that particles may take up more water than previously thought, potentially changing how long the particles remain in the atmosphere.

Research led by the University of Birmingham found pollutants that form nanostructures could absorb substantially more water than simple models have previously suggested. Taking on water means the droplets become heavier and will eventually be removed from the atmosphere when they fall as rain.

The team, also involving researchers ...

Breakthrough in the precision engineering of four-stranded β-sheets

2024-12-10

A newly developed approach can precisely produce four-stranded β-sheets through metal–peptide coordination, report researchers from Institute of Science Tokyo. Their innovative methodology overcomes long-standing challenges in controlled β-sheet formation, including fibril aggregation and uncontrolled isomeric variation in the final product. This breakthrough could advance the study and application of β-sheets in biotechnology and nanotechnology.

In addition to the natural sequence of amino acids that makes up a protein, their three-dimensional arrangement in space is also critical to their function. For ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] Tiny poops in the ocean may help solve the carbon problemA Dartmouth-led study turns CO2 into food that zooplankton expel into the deep sea.