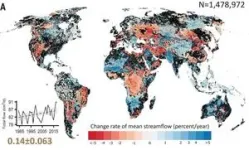

(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. — A new study in Science by researchers from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and University of Cincinnati has mapped 35 years of river changes on a global scale for the first time. The work has revealed that 44% of the largest, downstream rivers saw a decrease in how much water flows through them every year, while 17% of the smallest upstream rivers saw increases. These changes have implications for flooding, ecosystem disruption, hydropower development interference and insufficient freshwater supplies.

Previous attempts to quantify changes in rivers over time have only looked at specific outlet reaches or a rear basin part of a river, explains Dongmei Feng, lead author, assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati and former research assistant professor in the Fluvial@UMass lab run by the paper’s co-author Colin Gleason, Armstrong Professional Development Professor of civil and environmental engineering at UMass Amherst.

“But as we know, rivers are not isolated,” she says. “So even if we are interested in one location, we have to think about how it’s impacted both upstream and downstream. We think about the river system as a whole, organically connected system. The takeaway from this paper is: The rivers respond to factors — climate change or human regulation — differently [and] we provide the finer detail of those responses.”

River flow rate, also known as discharge, describes how much water flows through a river, measured in cubic meters per second or gallons per day. Currently, flow rate is measured by manually dragging a tool (called an acoustic doppler current profiler) across the surface of a river and then combining it with another automatic measurement of river depth to calculate flow rate over time. Because this approach and only measures flow rate at a specific location, at a specific time, data on flow rates are extremely limited.

“There are about 10-15,000 infinitesimally small slices around the world where we know river discharge — that’s it — out of millions and millions of miles of rivers,” says Gleason.

So Feng and Gleason developed a new approach using satellite data and computer modeling to capture this flow rate across 3 million stream reaches worldwide. “That’s every river, every day, everywhere, over a 35-year period,” Gleason says. “Some of these are changing by 5 or 10% per year. That’s rapid, rapid change. We had no idea what those flow rates were or how they were changing — which rivers are not like they used to be — now we know.”

The significant decreases found in downstream rivers mean that less fresh water is available on the largest parts of many rivers worldwide. This has significant impacts on drinking water and irrigation.

“Communities that use river water for irrigation and drinking water, if that’s dropping, then is there a sustainable use?” says Gleason. “Can you grow your town? Can you grow your city? Can you increase your number of [acres] in production? Can the river support it? We don’t know exactly why [this is happening], but we do know that’s what it might mean.”

The decrease in flow rate also means that the river has less power to move dirt and small rocks in the river bed. The movement of this sediment downstream builds deltas and is an important process in countering sea rise, so this loss of power is detrimental to deltas, especially in light of modern dam building limiting how much sediment is available to move.

Smaller, upstream rivers (typically closer to mountains) are showing an inverse pattern: 17% are seeing an increase in flow. (Though, Gleason points out, this is not uniform, as 10% are decreasing.) This increase in volume in these small rivers can have big impacts on their surrounding communities. The researchers found a 42% increase in large floods of these small streams. Gleason cites those that have occurred in Vermont in recent summers as an example.

“Floods are disastrous for humans, but for upstream species, they may be advantageous,” adds Feng. Flooding provides important nutrients and a means of travel for migrating fish. “The local people [near the western Amazon River], for example, have reported that the fish migration has increased in that region because the flooding is more frequent, which means the high flow required for fish migration is more frequent.”

This increase in upstream flow rate may also throw an unexpected wrench in hydropower plans, particularly in High Mountain Asia for places like Nepal and Bhutan. “The increased flow of the river channel means erosion power is much more significant than before and it’s transporting more sediment downstream,” says Feng. This becomes an issue for countries looking to develop more clean energy because this sediment can clog up hydropower plants.

While the paper cannot quantify the exact cause and effect, the researchers know that the general drivers of these changes are largely climate change and human activity. “Upstream river regions have increasing precipitation in general,” says Feng. “And the snow melt in the high elevation, which is typically cold, is probably more sensitive to climate change, so the snow melt has been increasing in these regions.” Human activity includes sourcing water from rivers for drinking or agriculture or wastewater dumping.

And Gleason adds that this paper is an important step: “If you don’t know what it is, you can’t figure out why it is. People who live along these rivers, of course, know there are problems, but if you’re a policy analyst and you’re trying to determine the best location for a new hydropower plant out of 100 candidates, it’s hard to measure 100 different rivers accurately. [Colleagues in water systems say] you would be shocked at how many places, particularly those that are resource-limited, make major decisions about climate futures, water resources, and infrastructure projects with almost no data on hand. My hope is that everyone can use these data, understand them, and maybe make a more informed decision.”

END

Floods, insufficient water, sinking river deltas: hydrologists map changing river landscapes across the globe

New research by the UMass Amherst and University of Cincinnati shows a rapid shift of water upstream over 35 years

2024-12-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Model enables study of age-specific responses to COVID mRNA vaccines in a dish

2024-12-12

mRNA vaccines clearly saved lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, but several studies suggest that older people had a somewhat reduced immune response to the vaccines when compared with younger adults. Why? Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital, led by Byron Brook, PhD, David Dowling, PhD, and Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, found some answers — while providing proof-of-concept of a new system that can model mRNA vaccine responses in a dish. This, in turn, could help expedite efforts to make ...

New grant to UMD School of Public Health will uncover “ghost networks” in Medicare plans

2024-12-12

COLLEGE PARK, Md. – Dr. Mika Hamer is about to go ghost hunting. Thanks to a $100K grant from the Robert Johnson Wood Foundation (RWJF), the University of Maryland School of Public Health researcher aims to uncover the extent of so-called “ghost networks” in Medicare Advantage health insurance plans.

A “ghost network” describes the difference between advertised in-network healthcare providers for a given insurance plan and the providers who are in fact available to deliver care to patients enrolled in those plans – meaning a patient ...

Researchers describe a potential target to address a severe heart disease in diabetic patients

2024-12-12

Some patients with diabetes develop a serious condition known as diabetic cardiomyopathy, which is slow and cannot be directly attributed to hypertension or other cardiovascular disorders. This often under-diagnosed heart function impairment is one of the leading causes of death in diabetic patients and it affects both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. There is no current specific drug treatment or clinical protocol approved to address this disease.

A study published in the journal Pharmacological Research describes a potential target that could spur the ...

U-M study of COVID-19 deaths challenges claims, understanding of pandemic-era suicides

2024-12-12

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, University of Michigan researchers dug deeper into the numbers-only data of COVID-19-era suicides and evaluated the narratives contained in reports from coroners, medical examiners, police and vital statistics.

The researchers sought to understand how the crisis influenced suicide deaths in the first year of the pandemic, how the response by governments, employers and others influenced individuals, and if their handling could inform future public health responses.

"Our study adds much-needed context and meaning to the data that have assumed the deaths are ...

How the dirt under our feet could affect human health

2024-12-12

Soil plays a much bigger role in the spread of antibiotic resistance than one might imagine.

Surprisingly, the ground beneath us is packed with antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) — tiny codes that allow bacteria to resist antibiotics. Human activities, such as pollution and changing land use, can disturb soil ecosystems and make it easier for resistance genes to transfer from soil bacteria and infect humans.

Jingqiu Liao, assistant professor in civil and environmental engineering, is on a mission to understand how soil bacteria contribute to ...

Screen time is a poor predictor of suicide risk, Rutgers researchers find

2024-12-12

For parents trying to shield their children from online threats, limiting screen time is a common tactic. Less time scrolling, the rationale goes, means less exposure to the psychological dangers posed by social media.

But research from Rutgers University-New Brunswick upends this assumption. Writing in The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Jessica L. Hamilton, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the School of Arts and Sciences, reports that screen time ...

Dual-unloading mode revolutionizes rice harvesting and transportation

2024-12-12

In a recent study published in Engineering, a team of researchers led by Wenyu Zhang from South China Agricultural University has developed a groundbreaking cotransporter system that combines a tracked rice harvester and transporter for fully autonomous harvesting, unloading, and transportation operations.

The key innovation of this system lies in the proposed dual-unloading mode, which includes two distinct methods: harvester waiting for unloading (HWU) and transporter following for unloading (TFU). In the HWU system, the harvester halts and summons the transporter when its ...

Researchers uncover strong light-matter interactions in quantum spin liquids

2024-12-12

Physicists have long theorized the existence of a unique state of matter known as a quantum spin liquid. In this state, magnetic particles do not settle into an orderly pattern, even at absolute zero temperature. Instead, they remain in a constantly fluctuating, entangled state. This unusual behavior is governed by complex quantum rules, leading to emergent properties that resemble fundamental aspects of our universe such as the interactions of light and matter. Despite its intriguing implications, experimentally proving ...

More dense, populated neighborhoods inspire people to walk more

2024-12-12

SPOKANE, Wash. – Adding strong evidence in support of “walkable” neighborhoods, a large national study found that the built environment can indeed increase how much people walk.

The study, published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, showed a strong connection between place and activity by studying about 11,000 twins, which helps control for family influences and genetic factors. The researchers found that each 1% increase in an area’s “walkability” resulted in 0.42% increase in neighborhood walking. When scaled up, that means a 55% increase in the walkability of the surrounding neighborhood ...

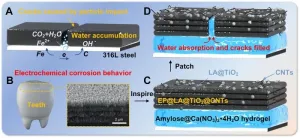

Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion

2024-12-12

The long-term erosion and corrosion issues during the development of offshore oil and gas fields pose significant threats to the safe and efficient operation of these facilities. Superhydrophobic coatings, known for their ability to reduce interactions between corrosive substances and substrates, have garnered considerable attention. However, their poor mechanical properties often hinder their long-term application in practical working environments. To address this challenge, a research team led by Prof. Yuekun Lai from Fuzhou University and Prof. Xuewen Cao from China University of Petroleum (East China) has developed a biomimetic dental enamel coating with ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Floods, insufficient water, sinking river deltas: hydrologists map changing river landscapes across the globeNew research by the UMass Amherst and University of Cincinnati shows a rapid shift of water upstream over 35 years