(Press-News.org) In a groundbreaking study published this week in The Journal of Physiology, biologists at the Marine Mammal Research Program (MMRP) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) used drone imagery to advance understanding of how lactating humpback whales and their calves fare as they traverse the Pacific Ocean. Recent declines in North Pacific humpback whale reproduction and survival of calves highlight an urgent need to understand how mother-calf pairs expend energy across their migratory cycle. This work, done in close partnership with Alaska Whale Foundation, Pacific Whale Foundation and other partners, provides unprecedented insight into the life history of humpback whales across their migratory cycle, and provides key baseline data for understanding how rapid changes in ocean ecosystems are impacting humpback whales.

The team used drone imagery to measure calf growth and maternal body condition days after calf birth in Hawaiʻi, and they then compared these measurements to the body conditions of humpback females in the Alaska feeding grounds, measuring pregnant and lactating females as well as humpback females whose reproductive status was unknown.

“We used drone-based photogrammetry to quantify the body size and condition of humpback whales on their Hawaiian breeding and Southeast Alaskan feeding grounds,” explains Martin van Aswegen, MMRP PhD candidate and lead author of the study. “A total of 2,410 measurements were taken from 1,659 individuals, with 405 repeat measurements from 137 lactating females used to track changes in maternal body volume over migration.”

The research shows that larger females produced larger, faster-growing calves. Over a 6-month period, lactating females decreased in body volume by an average of about 17%, whereas the calves’ body volume increased by nearly 395% and their length increased by almost 60%. In Hawaiʻi, the team discovered that on average, humpback whale mothers lose nearly 214 pounds of blubber per day. Over a 60-day period, this is equivalent to losing roughly 50 tons of krill, or 25 tons of Pacific herring. Mother humpbacks in Hawai‘i lost 20% of their body volume over 60 days of lactation, and the energy they used lactating surpassed the total energetic cost of their year-long pregnancies.

In the Southeast Alaskan feeding grounds, lactating humpback mothers were found to have the slowest rates of weight gain compared to non-lactating females, gaining about 32 pounds each day. Comparatively, pregnant and nonpregnant females gained weight at six and two times the rate of the lactating females, respectively.

“For me, the surprising part of this study was our ability to find the same individual mothers and calves over great distances and time periods,” shares van Aswegen. “For example, we obtained 405 repeat measurements from 137 lactating females in Hawai‘i and Southeast Alaska, with eight of those mother-calf pairs measured in both locations within the same year. To measure the same whales over 3,000 miles apart over a period of roughly 200 days is truly remarkable and provides such valuable data for the questions we were asking.”

In Hawai‘i, humpback whales are important cultural, economic, educational, and environmental pillars. Studies document a 76.5% decline in mother-calf encounter rates in Hawaiʻi between 2013-2018, with birth rates declining by 80% from 2015 to 2016. In the SE Alaskan feeding ground, research reveals total reproductive failure in 2018, with calf survival decreasing tenfold from 2014 to 2019. These observations coincided with the longest lasting global marine heatwave, which shifted food webs and reduced availability of prey throughout the North Pacific. It is believed that humpback whales were unable to acquire sufficient food in their feeding grounds, resulting in nutritional stress and notable declines in reproduction and abundance.

This new study by MMRP refines our understanding of the energetic requirements for humpback whales to produce offspring, and it also highlights the important role Hawai‘i holds as a critical breeding habitat. We now know that humpback whales are highly vulnerable during stages of early calf growth and lactation, which means it will be essential to carefully manage these waters. This information is key for considering how human activities could adversely impact not just humpback whale mother-calf pairs, but the survival of the humpback whale species.

“This work forms the basis for future studies investigating the energetic demands on humpback whales,” emphasizes Lars Bejder, MMRP director and co-author of the study. “Our humpback whale health database, comprising 11,000 measurements of 8,500 individual whales in the North Pacific, is being used across several projects within the Marine Mammal Research Program and abroad. These data become even more powerful when used in conjunction with fine-scale behavior and movement data (from biologging tags); reproductive and stress hormone data (from tissue and breath samples); and tissue data derived from post-mortem events. These studies will be used to better predict the resilience of large baleen whale species in the face of threats, including disturbance, entanglement, vessel collision, and climate change.”

Understanding and protecting humpback whales is a shared effort, requiring close partnership.

“Our ability to track individual humpback whales across thousands of miles and over months speaks to the power of collaboration,” notes Jens Currie, MMRP PhD candidate, Chief Scientist at Pacific Whale Foundation, and co-author of the study. “This study showcases how teamwork across disciplines and institutions helps us uncover the intricate relationships between maternal health, calf growth, and environmental stressors. Such partnerships are vital as we strive to protect humpback whales and their habitats amidst a changing climate.”

This work would not have been possible without many generous contributors. Hawaiʻi fieldwork was funded through the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa; DoD’s Defense University Research Instrumentation Program; 'Our Oceans,' Netflix, Wildspace Productions and Freeborne Media; Office of Naval Research; Omidyar Ohana Foundation; the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation; PacWhale Eco-Adventures as well as members and donors of Pacific Whale Foundation. Southeast Alaska research was funded through awards from the National Geographic Society (NGS), Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic (LEX-NG) Funds, and North Pacific Research Board. Graduate Assistantships for Martin van Aswegen were funded by a Denise B. Evans Oceanography Fellowship, North Pacific Research Board grant, and the Dolphin Quest General Science and Conservation Fund. Stranding response, necropsy and tissue processing of the humpback whale calf was supported by the NOAA John H. Prescott Marine Mammal Rescue Assistance Grant Program.

END

Using drones, UH researchers assess the health of humpback whale mother-calf pairs across the Pacific Ocean

2024-12-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Allen Institute names Julie Harris, Ph.D., as new Vice President of The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group

2024-12-17

SEATTLE, WASH.—December 17, 2024—The Allen Institute today announced the appointment of Julie Harris as the new Vice President of The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group. Harris was previously Executive Vice President of Research Management at the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund where she oversaw the funding strategy and research priorities for a ~$29 million grant portfolio in support of the most promising science and scientists working to end the burden of Alzheimer’s disease.

Between 2011 and 2020 Harris worked at the Allen Institute for Brain Science as ...

Bad bacteria can trigger painful gut contractions; new research shows how

2024-12-17

Downloadable assets for media use:

https://uoregon.canto.com/b/MSHJ8

EUGENE, Ore. — Dec. 18, 2024 — After a meal of questionable seafood or a few sips of contaminated water, bad bacteria can send your digestive tract into overdrive. Your intestines spasm and contract, efficiently expelling everything in the gut — poop and bacteria alike.

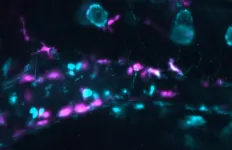

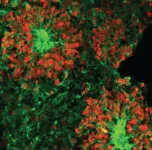

A new study from the University of Oregon shows how one kind of bacteria, Vibrio cholerae, triggers those painful contractions by activating the immune system. The research also finds a more general explanation for how the gut rids itself of unwanted intruders, which could also help scientists ...

Partnership advances targeted therapies for blood cancers

2024-12-17

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah (the U) has joined other institutions in an innovative clinical trials program designed to match patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) with a clinical trial specifically designed for the genetic signature of their disease. Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the myeloMATCH program aims to improve precision medicine, the use of therapies ...

How loss of urban trees affects education outcomes

2024-12-17

It’s well established that urban tree cover provides numerous environmental and psychological benefits to city dwellers. Urban trees may also bolster education outcomes and their loss could disproportionately affect students from low-income families, according to new research by University of Utah social scientists.

Economics professor Alberto Garcia looked at changes in school attendance and standardized test scores at schools in the Chicago metropolitan region over the decade after a non-native ...

New virtual reality-tested system shows promise in aiding navigation of people with blindness or low vision

2024-12-17

A new study offers hope for people who are blind or have low vision (pBLV) through an innovative navigation system that was tested using virtual reality. The system, which combines vibrational and sound feedback, aims to help users navigate complex real-world environments more safely and effectively.

The research from NYU Tandon School of Engineering, published in JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology, advances work from John-Ross Rizzo, Maurizio Porfiri and colleagues toward developing a first-of-its-kind ...

Brain cells remain healthy after a month on the International Space Station, but mature faster than brain cells on Earth

2024-12-17

LA JOLLA, CA—Microgravity is known to alter the muscles, bones, the immune system and cognition, but little is known about its specific impact on the brain. To discover how brain cells respond to microgravity, Scripps Research scientists, in collaboration with the New York Stem Cell Foundation, sent tiny clumps of stem-cell derived brain cells called “organoids” to the International Space Station (ISS).

Surprisingly, the organoids were still healthy when they returned from orbit a month later, but the cells had matured faster compared ...

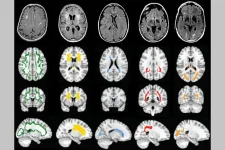

NIH grant funds study of cerebral small vessel disease

2024-12-17

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have been awarded $7.5 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to investigate a form of dementia caused by cerebral small vessel disease, the second-leading cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease.

The grant funds the Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (VCID) Center, which is a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke “Center Without Walls” initiative that will coordinate researchers at six sites across ...

Paranoia may be, in part, a visual problem

2024-12-17

New Haven, Conn. — Could complex beliefs like paranoia have roots in something as basic as vision? A new Yale study finds evidence that they might.

When completing a visual perception task, in which participants had to identify whether one moving dot was chasing another moving dot, those with greater tendencies toward paranoid thinking (believing others intend them harm) and teleological thinking (ascribing excessive meaning and purpose to events) performed worse than their counterparts, the study found. Those individuals more often — and confidently — claimed one dot was chasing the other when it wasn’t.

The findings, published Dec. 17 in ...

The high cost of carbon

2024-12-17

The social cost of carbon — an important figure that global policymakers use to analyze the benefits of climate and energy policies — is too low, according to a study led by the University of California, Davis.

The study, published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), shows that current estimates for the social cost of carbon, or SCC, fail to adequately represent important channels by which climate change could affect human welfare. When included, the SCC increases to just over $280 per ton of CO2 emitted in 2020 — more than double the ...

This mysterious plant fossil belongs to a family that no longer exists

2024-12-17

In 1969, fossilized leaves of the species Othniophyton elongatum — which translates to “alien plant” — were identified in eastern Utah. Initially, scientists theorized the extinct species may have belonged to the ginseng family (Araliaceae). However, a case once closed is now being revisited. New fossil specimens show that Othniophyton elongatum is even stranger than scientists first thought.

Steven Manchester, curator of paleobotany at the Florida Museum of Natural History, has studied 47-million-year-old fossils from Utah for several years. While visiting ...