(Press-News.org) If all the world's a stage and all the species merely players, then their exits and entrances can be found in the rock record.

Fossilized skeletons and shells clearly show how evolution and extinction unfolded over the past half a billion years, but a new Virginia Tech analysis extends the chart of life to nearly 2 billion years ago.

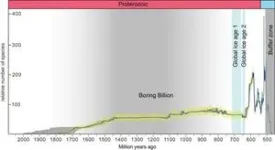

The chart shows the relative ups and downs in species counts, telling scientists about the origin, diversification, and extinction of ancient life.

With this new study, the chart of life now includes life forms from the Proterozoic Eon, 2,500 million to 539 million years ago. Proterozoic life was generally smaller and squishier — like sea sponges that didn’t develop mineral skeletons — and left fewer traces to fossilize in the first place.

Virginia Tech geobiologist Shuhai Xiao and collaborators published a high-resolution analysis of the global diversity of Proterozoic life based on a global compilation of fossil data, which was released Dec. 20 in the journal Science.

Xiao and his team looked specifically at records of ancient marine eukaryotes — organisms whose cells contain a nucleus. Early eukaryotes later evolved into the multicellular organisms credited for ushering in a whole new era for life on Earth, including animals, plants, and fungi.

“This is the most comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of this period to date,” said Xiao who recently was inducted into the National Academy of Sciences. “And more importantly, we’ve used a graphic correlation program that allowed us to achieve greater temporal resolution.”

The choreography of species offers critical insights into the parallel paths of the evolution of life and Earth.

Observed patterns and insights suggested by the analysis:

The first eukaryotes arose no later than 1.8 billion years ago and gradually evolved to a stable level of diversity from about 1,450 million to 720 million years ago, a period aptly known as the “boring billion,” when species turnover rates were remarkably low.

Eukaryotic species in the “boring billion” may have evolved slower and lasted longer than those came later.

Then cataclysm: Snowball Earth, a spiral of plunging temperatures, sealed the planet in ice at least twice between 720 million and 635 million years ago. When the ice eventually thawed, evolutionary activity picked up, and things weren’t so boring anymore.

“The ice ages were a major factor that reset the evolutionary path in terms of diversity and dynamics,” Xiao said. “We see rapid turnover of eukaryotic species immediately after glaciation. That’s a major finding.”

The patterns, Xiao said, raise a lot of interesting questions, including:

Why was eukaryotic evolution sluggish during the “boring billion”?

What factors contributed to the increased pace of evolution after snowball ice ages?

Was it environmental, such as climate changes and increases in atmospheric oxygen level?

Was it an evolutionary arms race between different organisms that could drive creatures to evolve quickly?

Future scientists can use the quantified pattern to answer these questions and better understand the complex interplay of life on Earth and the Earth itself.

Study collaborators include:

Qing Tang, first author, former graduate student and postdoctoral researcher, now at Nanjing University, as well as former graduate students Drew Muscente, now at Princeton Consultants, and Natalia Bykova, now at the University of Missouri, who worked in Xiao’s lab in the past decade

Researchers from the University of Hong Kong; University of California, Santa Barbara; Princeton Consultants; University of Missouri; Russian Academy of Sciences; University of California, Riverside; Chinese Academy of Sciences; and Northwest University (China) END

Virginia Tech study extends chart of life by nearly 1.5 billion years

Ancient species may have evolved slower and lasted longer, but the pace of evolution accelerated after global ice ages, according to a new Virginia Tech analysis. The study, published in the journal Science, maps the rise and fall of ancient life many tim

2024-12-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Seasonal flu vaccine study reveals host genetics’ role in vaccine response and informs way to improve vaccine

2024-12-19

Most people who get the seasonal influenza vaccine – which contains strains of viruses from distinct virus subtypes – mount a strong immune response to one strain, leaving them vulnerable to infection by the others, and researchers have long wondered what impacts such variable responses more – host genetics or prior exposure to virus strains. Now, researchers report that host genetics is a stronger driver of these individual differences in influenza vaccine response. Their study also presents a novel vaccine platform that improved protection against diverse influenza subtypes when tested in animal models and human organoids. ...

Filling a gap: New study uncovers Proterozoic eukaryote diversity, and how environment was a driver

2024-12-19

Advanced tools and expanded fossil datasets have painted a clearer picture of the eukaryotic diversity of the Proterozoic eon, which has been hard to quantify. The findings show that Earth's severe Cryogenian glaciations catalyzed a pivotal shift in the evolution and diversity of early eukaryotes during this eon, 2500 to 538 million years ago. This work underscores the interplay between Earth’s environmental perturbations and the evolutionary trajectories of early life. Quantifying global fossil diversity provides valuable insights into the evolutionary history of life on Earth and its relationship with environmental changes. This is exemplified by the well-known mass extinction ...

In aged mice with cognitive deficits, neuronal activity and mitochondrial function are decoupled

2024-12-19

New findings in mice have uncovered a crucial mechanism linking neuronal activity to mitochondrial function, researchers report, revealing a potential pathway to combat age-related cognitive decline. Mitochondria play a pivotal role in meeting the dynamic energy demands of neuronal activity, producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) primarily via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). However, in the aging mammalian brain, mitochondrial metabolism deteriorates, leading to profound effects on neuronal and circuit functionality. The breakdown of the OXPHOS pathway contributes to oxidative stress and ...

Discovered: A protein that helps make molecules for pest defense in Solanum species

2024-12-19

A protein – dubbed GAME15 – is the missing link in the pathway that Solanum plants like potatoes use to make molecules for chemical defense: steroidal glycoalkaloids (SGAs). The findings pave the way for engineering this biosynthetic pathway into other plants, enabling innovative applications in agriculture and biotechnology. “The discovery … provides a key to engineering SGAs for food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals,” write the authors. Plants produce a wide variety of secondary metabolites that are crucial for their growth ...

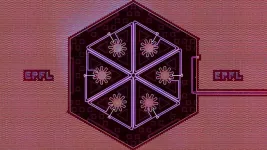

Macroscopic oscillators move as one at the quantum level

2024-12-19

Quantum technologies are radically transforming our understanding of the universe. One emerging technology are macroscopic mechanical oscillators, devices that are vital in quartz watches, mobile phones, and lasers used in telecommunications. In the quantum realm, macroscopic oscillators could enable ultra-sensitive sensors and components for quantum computing, opening new possibilities for innovation in various industries.

Controlling mechanical oscillators at the quantum level is essential for developing future technologies in quantum computing and ultra-precise ...

Early warning tool will help control huge locust swarms

2024-12-19

Desert locusts typically lead solitary lives until something - like intense rainfall - triggers them to swarm in vast numbers, often with devastating consequences.

This migratory pest can reach plague proportions, and a swarm covering one square kilometre can consume enough food in one day to feed 35,000 people. Such extensive crop destruction pushes up local food prices and can lead to riots and mass starvation.

Now a team led by the University of Cambridge has developed a way to predict when and where desert locusts will swarm, so they can be dealt with before the problem ...

Study shows role of cells’ own RNA in antiviral defense

2024-12-19

Scientists have uncovered a new role for a cell’s own RNA in fending off attacks by RNA viruses. Some of the cell’s RNA molecules, researchers found, help regulate antiviral signaling. These signals are part of the intricate coordination of immune responses against virus invasion.

A paper this week in Science reports how cellular RNA carries out its infection-controlling function.

“With RNA increasingly seen as both a drug and a druggable target,” the scientists wrote, “this opens the potential for RNA-based therapeutics for combating both infection and autoimmunity.”

The senior investigator is Ram Savan, professor of immunology at the ...

Are particle emissions from offshore wind farms harmful for blue mussels?

2024-12-19

After several years of service under harsh weather conditions, the rotor blades of offshore wind parks are subjected to degradation and surface erosion, releasing sizeable quantities of particle emissions into the environment. A team of researchers led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now investigated the effects of these particle on blue mussels – a species also being considered for the multi-use of wind parks for aquaculture. In the experiment, the mussels absorbed metals from the rotor blades’ coatings, as the team describes in a study just released in the journal Science of the Total Environment, where they also discuss ...

More is not always better: Hospitals can reduce the number of hand hygiene observations without affecting data quality

2024-12-19

Arlington, Va., December 19, 2024 – Hand hygiene (HH) monitoring in hospitals could be reduced significantly, allowing infection preventionists to redirect efforts toward quality improvement and patient safety initiatives, according to a new study published in the American Journal of Infection Control. The study’s findings suggest that hospitals could reduce the number of HH observations from 200 to as few as 50 observations per unit per month without compromising data quality.

Hand hygiene is the simplest ...

Genetic discovery links new gene to autism spectrum disorder

2024-12-19

TORONTO, CA – New research published in The American Journal of Human Genetics has identified a previously unknown genetic link to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The study found that variants in the DDX53 gene contribute to ASD, providing new insights into the genetic underpinnings of the condition.

ASD, which affects more males than females, encompasses a group of neurodevelopmental conditions that result in challenges related to communication, social understanding and behaviour. While DDX53, located on the X chromosome, is known to play a role in brain development and function, it was not previously definitively associated with autism.

In ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Carsten Bönnemann, MD, joins St. Jude to expand research on pediatric catastrophic neurological disorders

Women use professional and social networks to push past the glass ceiling

Trial finds vitamin D supplements don’t reduce covid severity but could reduce long COVID risk

Personalized support program improves smoking cessation for cervical cancer survivors

Adverse childhood experiences and treatment-resistant depression

Psilocybin trends in states that decriminalized use

New data signals high demand in aesthetic surgery in southern, rural U.S. despite access issues

$3.4 million grant to improve weight-management programs

Higher burnout rates among physicians who treat sickle cell disease

Wetlands in Brazil’s Cerrado are carbon-storage powerhouses

Brain diseases: certain neurons are especially susceptible to ALS and FTD

Father’s tobacco use may raise children’s diabetes risk

Structured exercise programs may help combat “chemo brain” according to new study in JNCCN

The ‘croak’ conundrum: Parasites complicate love signals in frogs

Global trends in the integration of traditional and modern medicine: challenges and opportunities

Medicinal plants with anti-entamoeba histolytica activity: phytochemistry, efficacy, and clinical potential

What a releaf: Tomatoes, carrots and lettuce store pharmaceutical byproducts in their leaves

Evaluating the effects of hypnotics for insomnia in obstructive sleep apnea

A new reagent makes living brains transparent for deeper, non-invasive imaging

Smaller insects more likely to escape fish mouths

Failed experiment by Cambridge scientists leads to surprise drug development breakthrough

Salad packs a healthy punch to meet a growing Vitamin B12 need

Capsule technology opens new window into individual cells

We are not alone: Our Sun escaped together with stellar “twins” from galaxy center

Scientists find new way of measuring activity of cell editors that fuel cancer

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

[Press-News.org] Virginia Tech study extends chart of life by nearly 1.5 billion yearsAncient species may have evolved slower and lasted longer, but the pace of evolution accelerated after global ice ages, according to a new Virginia Tech analysis. The study, published in the journal Science, maps the rise and fall of ancient life many tim