(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY--New work by Columbia researchers has turned a textbook principle of genetics on its head and revealed why some people who carry disease-causing genes experience no symptoms.

Every biology student learns that each cell in our body (except sperm and eggs) contains two copies of each gene, one from each parent, and each copy plays an equal part in the cell.

The new study shows that some cells are often biased when it comes to some genes and inactivate one parent’s copy. The phenomenon was discovered about a decade ago, but the new study shows how it can influence disease outcomes. The Columbia researchers looked at certain immune cells of ordinary people to get an estimate of the phenomenon and found that these cells had inactivated the maternal or paternal copy of a gene for one out of every 20 genes utilized by the cell.

“This is suggesting that there is more plasticity in our DNA than we thought before,” says study leader Dusan Bogunovic, professor of pediatric immunology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

“So in some cells in your body every 20th gene can be a little bit more Mom, a little bit less Dad, or vice versa. And to make thing even more complicated, this can be different in white blood cells than in the kidney cells, and it can perhaps change with time.”

The results were published Jan. 1 in the journal Nature.

Why it matters

The new study explains a longstanding puzzle in medicine: why do some people who’ve inherited a disease-causing mutation experience fewer symptoms than others with the same mutation? “In many diseases, we’ll see that 90% of people who carry a mutation are sick, but 10% who carry the mutation don’t get sick at all,” says Bogunovic, a scientist who studies children with rare immunological disorders at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Enlisting an international team of collaborators, the researchers looked at several families with different genetic disorders affecting their immune systems. In each case, the disease-causing copy was more likely to be active in sick patients and suppressed in healthy relatives who had inherited the same genes.

“There was some speculation that this bias toward one copy or the other could explain wide differences in the severity of a genetic disease, but no experimental evidence existed until now,” Bogunovic says.

Though the current work looked only at immune cells, Bogunovic says the selective bias for the maternal or paternal copy of a gene affected more than just immune-related genes. “We don’t see a preference for immune genes or any other class of genes, so we think this phenomenon can explain the wide variability in disease severity we see with many other genetic conditions,” he says, adding “this could be just the tip of the iceberg.”

The phenomenon could help explain diseases with flares, like lupus, or those that emerge following environmental triggers. It could also play a role in cancer.

Changing the future of treatments for genetic diseases?

The study’s findings point to an entirely new paradigm for diagnosing and perhaps even treating inherited diseases.

The investigators propose expanding the standard characterization of genetic diseases to include patients’ “transcriptotypes,” their gene activity patterns, in addition to their genotypes.

“This changes the paradigm of testing beyond your DNA to your RNA, which as we’ve shown in our study, is not equal in all cell types and can change over time,” says Bogunovic.

If researchers can identify the mechanisms behind selective gene inactivation, they may also be able to treat genetic diseases in a new way, by switching a patient’s gene expression pattern to suppress the undesirable copy. While emphasizing that such strategies are still far from clinical use, Bogunovic is optimistic: “At least in cell culture in the lab we can do it, so manipulation in that way is something that could turn somebody’s genetic disease into non-disease, assuming we are successful.”

Additional information

"Monoallelic expression can govern penetrance of inborn errors of immunity(link is external and opens in a new window)," was published Jan. 1 in Nature.

All authors: O’Jay Stewart (Columbia), Conor Gruber (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), Haley E. Randolph (Columbia), Roosheel Patel (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), Meredith Ramba (Columbia), Enrica Calzoni (Columbia), Lei Haley Huang (Columbia), Jay Levy (Columbia), Sofija Buta (Columbia), Angelica Lee (Columbia), Christos Sazeides (Columbia), Zoe Prue (Columbia), David P. Hoytema van Konijnenburg (Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School), Ivan K. Chinn (Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital), Luis A. Pedroza (Columbia), James R. Lupski (Baylor), Erica G. Schmitt (Washington University School of Medicine), Megan A. Cooper (Washington University School of Medicine), Anne Puel (INSERM, University of Paris Cité, and Necker Hospital for Sick Children), Xiao Peng (Johns Hopkins), Stéphanie Boisson-Dupuis (INSERM, University of Paris Cité, and Necker Hospital for Sick Children), Jacinta Bustamante (INSERM, University of Paris Cité, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, and Rockefeller University), Satoshi Okada (Hiroshima University), Marta Martin-Fernandez (Columbia and Instituto de Salud Carlos III), Jordan S. Orange (Columbia), Jean-Laurent Casanova (INSERM, University of Paris Cité, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, Rockefeller University, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute), Joshua D. Milner (Columbia) & Dusan Bogunovic (Columbia).

###

Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) is a clinical, research, and educational campus located in New York City. Founded in 1928, CUIMC was one of the first academic medical centers established in the United States of America. CUIMC is home to four professional colleges and schools that provide global leadership in scientific research, health and medical education, and patient care including the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing. For more information, please visit cuimc.columbia.edu.

END

What happens when some cells are more like Dad than Mom

A new study reveals why some people who carry disease-causing genes have no symptoms

2025-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

CAR-T cells hold memories of past encounters

2025-01-02

AURORA, Colo. (Jan. 2, 2025) - Researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have discovered that some CAR-T cells engineered to fight cancer and other conditions carry the memory of past encounters with bacteria, viruses and other antigens within them, a finding that may allow scientists to manufacture the cells in more precise and targeted ways.

The study, published today in the journal Nature Immunology, focused on chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, an effective therapy against ...

Quantity over quality? Different bees are attracted to different floral traits

2025-01-02

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — When it comes to deciding where they’re going to get their next meal, different species of bees may be attracted to different flower traits, according to a study led by researchers at Penn State and published in PNAS Nexus.

The study focused on two species of solitary bees: the horned-face bee, which helps pollinate crops like apples and blueberries, and the alfalfa leafcutting bee, which pollinates alfalfa.

The researchers found that the horned-face bees tended to prefer plants with a large number of flowers — for them, quantity was most important. ...

Cancer-preventing topical immunotherapy trains the immune system to fight precancers

2025-01-02

A new study by investigators from Mass General Brigham uncovers how a novel immunotherapy prevents squamous cell carcinoma, with benefits lasting five years after treatment. This therapy is the first to activate specific components of the adaptive immune system, particularly CD4+ T helper cells, which are not known to be involved in traditional cancer treatments. This work highlights the potential for similar immunotherapies to prevent other cancers throughout the body. Results are published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

“One of the unique challenges with squamous cell carcinoma is that individuals who develop it are at an increased risk of developing multiple new ...

Blood test can predict how long vaccine immunity will last, Stanford Medicine-led study shows

2025-01-02

When children receive their second measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, around the time they start kindergarten, they gain protection against all three viruses for all or most of their lives. Yet the effectiveness of an influenza vaccine given in October starts to wane by the following spring.

Scientists have long been stymied by why some vaccines can coax the body to produce antibodies for decades, while others last mere months. Now, a study led by researchers at Stanford Medicine has shown that variation in vaccine durability can, in part, be pinned on a surprising type ...

The nose knows: Nasal swab detects asthma type in kids

2025-01-02

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have developed a nasal swab test for kids that diagnoses specific asthma subtype, or endotype. This non-invasive approach could help clinicians prescribe medications more precisely and pave the way for research toward better treatments for lesser-studied asthma types, which have been difficult to diagnose accurately until now.

Published today in JAMA, the findings are based on data from three independent U.S.-based studies that focused on Puerto Rican and African American youths, who have higher rates of asthma and are more likely to die from the disease than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

“Asthma ...

Knowledge and worry following review of standard vs patient-centered pathology reports

2025-01-02

About The Study: Most study participants could not extract basic information—including whether they have cancer—from standard prostate cancer pathology reports but were able to understand this diagnostic information from the patient-centered pathology reports (PCPRs). Also, they discriminated between risk levels (i.e., lower levels of perceived worry in the low-risk condition) with PCPRs compared with standard reports. Hospital systems should consider including PCPRs with standard pathology reports to improve patient understanding.

Corresponding ...

Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer stage at diagnosis

2025-01-02

About The Study: This case-control study found that individuals with more advanced breast cancer at diagnosis were more likely to have prevalent cardiovascular disease. This finding may be specific to hormone receptor–positive and ERBB2-negative (formerly HER2) disease. Future studies are needed to confirm these findings and investigate interventions to improve patient outcomes, including personalized cancer screening.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Kevin T. Nead, MD, MPhil, email ktnead@mdanderson.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52890)

Editor’s ...

Herpes virus might drive Alzheimer's pathology, study suggests

2025-01-02

PITTSBURGH, Jan. 2, 2025 – University of Pittsburgh researchers uncovered a surprising link between Alzheimer’s disease and herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), suggesting that viral infections may play a role in the disease. The study results are published today in Cell Reports.

The study also revealed how tau protein, often viewed as harmful in Alzheimer’s, might initially protect the brain from the virus but contribute to brain damage later. These findings could lead to new treatments targeting infections and the brain’s immune response.

“Our study challenges ...

Patients with heart disease may be at increased risk for advanced breast cancer

2025-01-02

HOUSTON ― Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer are the two leading causes of death in the U.S. According to researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, patients diagnosed with late-stage or metastatic breast cancer have a statistically significant increased risk of pre-diagnosis CVD compared to those with early-stage cancer at diagnosis.

The study, published today in JAMA Network Open, found those with advanced breast cancer at diagnosis were 10% more likely to have had pre-existing ...

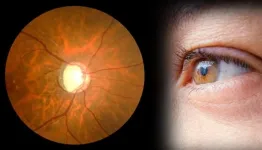

Chinese Medical Journal study reveals potential use of artificial intelligence (AI) in finding new glaucoma drugs

2025-01-02

Glaucoma is a progressive eye disorder characterized by fluid buildup inside the eye, causing ocular hypertension. By 2040, it is estimated that 111.8 million people worldwide will be affected by glaucoma, potentially leading to blindness if left untreated. Currently, there are treatments available to manage ocular hypertension, but a cure for glaucoma remains elusive.

Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are crucial for transmitting visual signals from the eyes to the brain, and their degeneration leads to optic nerve damage, which is a hallmark of glaucoma. In recent years, scientists ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

[Press-News.org] What happens when some cells are more like Dad than MomA new study reveals why some people who carry disease-causing genes have no symptoms