(Press-News.org) UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 10AM (UK TIME) FRIDAY 3 JANUARY 2025.

Peer reviewed | Observational study | Cells

A genetic fault long believed to drive the development of oesophageal cancer may in fact play a protective role early in the disease, according to new research published in Nature Cancer. This unexpected discovery could help doctors identify which individuals are at greater risk of developing cancer, potentially leading to more personalised and effective preventive strategies.

“We often assume that mutations in cancer genes are bad news, but that’s not the whole story,” says lead researcher Francesca Ciccarelli, Professor of Cancer Genomics at Queen Mary University of London’s Barts Cancer Institute and Principal Group Leader at the Francis Crick Institute, where the experimental work in this study took place. “The context is crucial. These results support a paradigm shift in how we think about the effect of mutations in cancer.”

This research was funded by Cancer Research UK and the experimental work in this study took place at the Francis Crick Institute.

A new understanding of oesophageal cancer risk

Just 12% of patients with oesophageal cancer in England survive their disease for 10 years or more. The UK has one of the world’s highest incidences of a subtype called oesophageal adenocarcinoma, and cases continue to increase. This cancer type develops from a condition called Barrett’s oesophagus, in which the cells lining the oesophagus become abnormal. However, only around 1% of people with Barrett’s go on to develop cancer each year. In the new study, the research team sought to better understand why some cases of Barrett’s lead to cancer, while others do not, to support better prediction and treatment of oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

The team analysed a large gene sequencing dataset from more than 1,000 people with oesophageal adenocarcinoma and more than 350 people with Barrett’s oesophagus, including samples from the OCCAMS consortium*. They found that defects in a gene called CDKN2A were more common in people with Barrett’s oesophagus who never progressed to cancer. This finding was unexpected, as CDKN2A is commonly lost in various cancers and is well-known as a tumour suppressor gene – a molecular safeguard that stops cancer from forming.

The research showed that if normal cells in our oesophagus lose CDKN2A, it helps promote the development of Barrett’s oesophagus. However, it also protects cells against the loss of another key gene encoding p53 – a critical tumour suppressor often dubbed the ‘guardian of the genome’. Loss of p53 strongly drives the progression of disease from Barrett’s to cancer.

The team found that potentially cancerous cells that lost both CDKN2A and p53 were weakened and unable to compete with other cells around them, preventing cancer from taking root. In contrast, if cancer cells lose CDKN2A after the disease has had time to develop, it promotes a more aggressive disease and worse outcomes for patients.

A gene with two faces

Professor Ciccarelli likens the dual role of CDKN2A to the ancient Roman god of transitions Janus, after whom January is named. Janus has two faces – one looking to the past and one to the future.

“It can be tempting to look at cancer mutations as good or bad, black or white. But like Janus, they can have multiple faces – a dual nature,” she explains. “We’re increasingly learning that we all accumulate mutations as an inevitable part of ageing. Our findings challenge the simplistic perception that these mutations are ticking time bombs and show that, in some cases, they can even be protective.”

The findings could have significant implications for how we assess cancer risk. They suggest that if a person with Barrett’s oesophagus has an early CDKN2A mutation but no mutations in p53, it could indicate that their condition is less likely to progress to cancer. On the other hand, later in the disease, CDKN2A mutations may signal a poor prognosis. Further research is needed to determine how to best apply this new knowledge to benefit patients in the clinic.

Science Engagement Manager at Cancer Research UK, Dr Nisharnthi Duggan, said: “Survival for oesophageal cancer has improved since the 1970s, but it’s still one of the most challenging cancers to treat. This is largely because it’s often diagnosed at advanced stages, when treatments are less likely to be successful.

"Funding research like this is critical to advancing our understanding and improving outcomes for people affected by the disease. It shows the importance of discovery science in unravelling the complexities of cancer, so we can identify new ways to prevent, detect and treat it."

ENDS

NOTES FOR EDITORS:

*OCCAMS consortium = the Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification is a network of clinical centres across the UK recruiting patients with oesophageal and gastro oesophageal junction (GOJ) adenocarcinoma

Contact:

Honey Lucas, Faculty Communications Officer – Medicine and Dentistry

press@qmul.ac.uk

Paper details:

Piyali Ganguli, et al. “Context-dependent effects of CDKN2A and other 9p21 gene losses during the evolution of oesophageal cancer.” Published in Nature Cancer.

DOI: 10.1101/2024.01.24.576991

Available after publication at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43018-024-00876-0

Under strict embargo until 10AM (UK TIME) FRIDAY 3 JANUARY 2025

A copy of the paper is available upon request.

Funding information:

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK.

All computational work of this study was conducted using the High-Performance Computer facility of the Cancer Research UK City of London Centre: a world-leading centre of excellence in cancer biotherapeutics that brings together researchers from Queen Mary University of London (including the Barts Cancer Institute and Wolfson Institute of Population Health), University College London, King's College London and The Francis Crick Institute.

Competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

About Queen Mary University of London

At Queen Mary University of London, we believe that a diversity of ideas helps us achieve the previously unthinkable.

Throughout our history, we’ve fostered social justice and improved lives through academic excellence. And we continue to live and breathe this spirit today, not because it’s simply ‘the right thing to do’ but for what it helps us achieve and the intellectual brilliance it delivers.

Our reformer heritage informs our conviction that great ideas can and should come from anywhere. It’s an approach that has brought results across the globe, from the communities of east London to the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

We continue to embrace diversity of thought and opinion in everything we do, in the belief that when views collide, disciplines interact, and perspectives intersect, truly original thought takes form.

The Francis Crick Institute is a biomedical discovery institute dedicated to understanding the fundamental biology underlying health and disease. Its work is helping to understand why disease develops and to translate discoveries into new ways to prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

An independent organisation, its founding partners are the Medical Research Council (MRC), Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London and King’s College London.

The Crick was formed in 2015, and in 2016 it moved into a brand new state-of-the-art building in central London which brings together 1500 scientists and support staff working collaboratively across disciplines, making it the biggest biomedical research facility under a single roof in Europe.

http://crick.ac.uk/

END

Surprising ‘two-faced’ cancer gene role supports paradigm shift in predicting disease

2025-01-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Growing divide: Agricultural climate policies affect food prices differently in poor and wealthy countries

2025-01-03

“In high-income countries like the U.S. or Germany, farmers receive less than a quarter of food spending, compared to over 70 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa, where farming costs make up a larger portion of food prices,” says David Meng-Chuen Chen, PIK scientist and lead author of the study published in Nature Food. “This gap underscores how differently food systems function across regions.” The researchers project that as economies develop and food systems industrialise, farmers will increasingly receive a smaller share of consumer spending, a measure known as the ‘farm ...

New approaches against metastatic breast cancer: mini-tumors from circulating cancer cells

2025-01-03

Tumor cells circulating in the blood are the “germ cells” of breast cancer metastases. They are very rare and could not be propagated in the culture dish until now, which made research into therapy resistance difficult. A team from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), the Heidelberg Stem Cell Institute HI-STEM* and the NCT Heidelberg** has now succeeded for the first time in cultivating stable tumor organoids directly from blood samples of breast cancer patients. Using these mini-tumors, the researchers ...

Loneliness linked to higher risk of heart disease and stroke and susceptibility to infection

2025-01-03

Interactions with friends and family may keep us healthy because they boost our immune system and reduce our risk of diseases such as heart disease, stroke and type 2 diabetes, new research suggests.

Researchers from the UK and China drew this conclusion after studying proteins from blood samples taken from over 42,000 adults recruited to the UK Biobank. Their findings are published today in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Social relationships play an important role in our wellbeing. Evidence increasingly ...

Some bacteria evolve like clockwork with the seasons

2025-01-03

Like Bill Murray in the movie “Groundhog Day,” bacteria species in a Wisconsin lake are in a kind of endless loop that they can’t seem to shake. Except in this case, it’s more like Groundhog Year.

According to a new study in Nature Microbiology, researchers found that through the course of a year, most individual species of bacteria in Lake Mendota rapidly evolved, apparently in response to dramatically changing seasons. Gene variants would rise and fall over generations, yet hundreds of separate species would return, almost fully, to near copies of what they had been genetically prior to a thousand or so generations of evolutionary pressures. (Individual microbes ...

New imaging technique offers insight into Achilles tendon injury recovery

2025-01-03

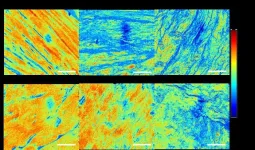

Achilles tendon injuries are common but challenging to monitor during recovery due to the limitations of current imaging techniques. Researchers, led by Associate Professor Zeng Nan from the International Graduate School at Shenzhen, Tsinghua University, have applied Mueller matrix polarimetry, a non-invasive imaging method, to more accurately observe and evaluate the healing of Achilles tendon injuries. This technique offers unique insights by capturing the subtle changes in tendon tissue without needing labels or dyes, allowing for more natural tissue characterization.

The study used Mueller ...

Bereavement science researcher provides insights on parasocial grief

2025-01-03

MIAMI, FLORIDA (Jan. 2, 2025) – Many people are surprised by the intensity of their response when a well-known person dies, and their feelings of sadness may last longer than they expect. In fact, that sadness and grief can be intense, and preliminary research suggests that grief after the death of a public figure looks very similar to grief over our personal relationships and can have comparable levels of intensity.

Wendy Lichtenthal, Ph.D., a bereavement science researcher, is available to discuss “parasocial grief” – that which occurs when a celebrity, political ...

New research aims to improve bridge construction in Texas

2025-01-02

A groundbreaking method for bridge construction is set to enhance performance, reduce construction time, and cut costs for future bridges across Texas.

Dr. Kinsey Skillen, assistant professor in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at Texas A&M University, was named Principal Investigator (PI) of the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) research project titled “Develop/Refine Design Provisions for Headed and Hooked Reinforcement.”

The 42-month project, which received nearly $1 million in funding, is a joint effort between the Texas Transportation Institute and the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) exploring more efficient methods ...

These bacteria perform a trick that could keep plants healthy

2025-01-02

To stay healthy, plants balance the energy they put into growing with the amount they use to defend against harmful bacteria. The mechanisms behind this equilibrium have largely remained mysterious.

Now, engineers at Princeton have found an answer in an unexpected place: the harmless, or sometimes beneficial, bacteria that cluster around plants’ roots.

In an article published Dec. 24 in the journal Cell Reports, researchers showed that some types of soil bacteria can influence a plant’s ...

Expanding the agenda for more just genomics

2025-01-02

Genomics is being integrated into biomedical research, medicine, and public health at a rapid pace, but the capacities necessary to ensure the fair, global distribution of benefits are lagging. A new special report outlines opportunities to enhance justice in genomics, toward a world in which genomic medicine promotes health equity, protects privacy, and respects the rights and values of individuals and communities.

The report, “Envisioning a More Just Genomics,” is a collaboration between ...

Detecting disease with only a single molecule

2025-01-02

UC Riverside scientists have developed a nanopore-based tool that could help diagnose illnesses much faster and with greater precision than current tests allow, by capturing signals from individual molecules.

Since the molecules scientists want to detect -- generally certain DNA or protein molecules -- are roughly one-billionth of a meter wide, the electrical signals they produce are very small and require specialized detection instruments.

“Right now, you need millions of molecules to detect ...