(Press-News.org) UC Riverside scientists have developed a nanopore-based tool that could help diagnose illnesses much faster and with greater precision than current tests allow, by capturing signals from individual molecules.

Since the molecules scientists want to detect -- generally certain DNA or protein molecules -- are roughly one-billionth of a meter wide, the electrical signals they produce are very small and require specialized detection instruments.

“Right now, you need millions of molecules to detect diseases. We’re showing that it’s possible to get useful data from just a single molecule,” said Kevin Freedman, assistant professor of bioengineering at UCR and lead author of a paper about the tool in Nature Nanotechnology. “This level of sensitivity could make a real difference in disease diagnostics.”

Freedman’s lab aims to build electronic detectors that behave like neurons in the brain and can retain memories: specifically, memories of which molecules previously passed through the sensor. To do this, the UCR scientists developed a new circuit model that accounts for small changes to the sensor’s behavior.

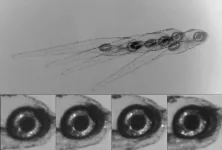

At the core of their circuit is a nanopore—a tiny opening through which molecules pass one at a time. Biological samples are loaded into the circuit along with salts, which dissociate into ions.

If protein or DNA molecules from the sample pass through the pore, this reduces the flow of ions that can pass. “Our detector measures the reduction in flow caused by a protein or bit of DNA passing through and blocking the passage of ions,” Freedman said.

To analyze the electrical signals generated by the ions, Freedman suggests, the system needs to account for the likelihood that some molecules may not be detected as they pass through the nanopore.

What distinguishes this discovery is that the nanopore is not just a sensor but itself acts as a filter, reducing background noise from other molecules in a sample that could obscure critical signals.

Traditional sensors require external filters to remove unwanted signals, and these filters can accidentally remove valuable information from the samples. Freedman’s approach ensures that each molecule’s signal is preserved, boosting accuracy for diagnostic applications.

Freedman envisions the device being used to develop a small, portable diagnostic kit—no larger than a USB drive—that could detect infections in the earliest stages. While today’s tests may not register infections for several days after exposure, nanopore sensors could detect infections within 24 to 48 hours. This capability would provide a significant advantage for fast-spreading diseases, enabling earlier intervention and treatment.

“Nanopores offer a way to catch infections sooner—before symptoms appear and before the disease spreads,” Freedman said. “This kind of tool could make early diagnosis much more practical for both viral infections and chronic conditions.”

In addition to diagnostics, the device holds promise for advancing protein research. Proteins perform essential roles in cells, and even slight changes in their structure can affect health. Current diagnostic tools struggle to tell the difference between healthy and disease-causing proteins because of their similarities. The nanopore device, however, can measure subtle differences between individual proteins, which could help doctors design more personalized treatments.

The research also brings scientists closer to achieving single molecule protein sequencing, a long-sought goal in biology. While DNA sequencing reveals genetic instructions, protein sequencing provides insight into how those instructions are expressed and modified in real time. This deeper understanding could lead to earlier detection of diseases and more precise therapies tailored to each patient.

“There’s a lot of momentum toward developing protein sequencing because it will give us insights we can’t get from DNA alone,” Freedman said. “Nanopores allow us to study proteins in ways that weren’t possible before.”

Nanopores are the focus of a funded research grant that Freedman was awarded by the National Human Genome Research Institute in which his team will attempt to sequence single proteins. This work builds on Freedman’s previous research on refining the use of nanopores for sensing molecules, viruses, and other nanoscale entities. He sees these advances as a sign of how molecular diagnostics and biological research may shift in the future.

“There’s still a lot to learn about the molecules driving health and disease,” Freedman said. “This tool moves us one step closer to personalized medicine.”

Freedman expects that nanopore technology will soon become a standard feature in both research and healthcare tools. As the devices become more affordable and accessible, they could find a place in everyday diagnostic kits used at home or in clinics.

“I’m confident that nanopores will become part of everyday life,” Freedman said. “This discovery could change how we’ll use them moving forward.”

END

Detecting disease with only a single molecule

Nanopore-based sensors could transform diagnostics

2025-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Robert McKeown recognized for a half century of distinguished service

2025-01-02

NEWPORT NEWS, VA – For nearly half a century, Robert D. “Bob” McKeown has probed nuclear particles and educated rising generations of physicists. Now, the former deputy director for science at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility is being honored for his outstanding career contributions with the 2024 American Physical Society’s Division of Nuclear Physics (DNP) Distinguished Service Award.

McKeown is recognized for his work in experimental physics and his extensive leadership in the broader ...

University of Maryland awarded $7.8 million to revolutionize renewable energy for ocean monitoring devices

2025-01-02

University of Maryland researcher Stephanie Lansing received a Phase 1 $7.8M award from Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop and test a biologically fueled energy source to power research and sensing devices throughout the world’s oceans.

There is a vast array of ocean sensing devices that provide critical information for understanding marine environments, monitoring climate change and maintaining national security. Many of these sensors are currently powered by long underwater cables or lithium-ion batteries.

Lansing is leading a large, collaborative effort that will overcome the need for batteries and ship-based or shore-based ...

Update: T cells may offer some protection in an H5N1 ‘spillover’ scenario

2025-01-02

Update: This LJI study was previously shared on bioRxiv in September 2024. Since then, health officials have reported a rise in H5N1 “bird flu” infections in humans, including the first severe H5N1 human case requiring hospitalization. Officials have also reported increased cases in feline species, including an outbreak among big cats at a wildlife sanctuary. In California, the recent spread of H5N1 to dairy herds in Southern California prompted Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a “State of Emergency” on Dec. 18, 2024.

LA JOLLA, CA—New research led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) ...

Newborn brain circuit stabilizes gaze

2025-01-02

An ancient brain circuit, which enables the eyes to reflexively rotate up as the body tilts down, tunes itself early in life as an animal develops, a new study finds.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the study revolves around how vertebrates, which includes humans and animals spanning evolution from primitive fish to mammals, stabilize their gaze as they move. To do so they use a brain circuit that turns any shifts in orientation sensed by the balance (vestibular) system in their ears into an instant counter-movement by their eyes.

Called ...

Bats surf storm fronts during continental migration

2025-01-02

Birds are the undisputed champions of epic travel—but they are not the only long-haul fliers. A handful of bats are known to travel thousands of kilometers in continental migrations across North America, Europe, and Africa. The behavior is rare and difficult to observe, which is why long-distance bat migration has remained an enigma. Now, scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior (MPI-AB) have studied 71 common noctule bats on their spring migration across the European continent, providing a leap in understanding this mysterious behavior. Ultra-lightweight, intelligent sensors attached ...

Canadian forests are more prone to severe wildfires in recent decades

2025-01-02

Climate change is driving more intense wildfires in Canada, according to a new modeling study, with fuel aridity and rising temperatures amplifying burn severity, particularly over the last several decades. The findings underscore the growing impact of climate change on wildfire behavior, with the most severe effects concentrated in Canada’s northern forests. Fueled by ongoing climate change, Canada – one of the most forested and fire-prone regions in the Northern Hemisphere – is grappling with increasingly severe and prolonged wildfire seasons. ...

Secrets of migratory bats: They “surf” storm front winds to save energy

2025-01-02

A species of migrating bat “surfs” the warm winds of incoming storm fronts to conserve energy, according to a study that used tags to track the tiny animals on their long journeys across central Europe. The findings offer new insights into how weather, physiology, and environmental factors shape bats’ seasonal migration patterns. While bird migration is well-documented and studied, this is not the case for seasonal migration of bats – particularly the few long-distance, migratory species. These nocturnal travelers face substantial challenges, ...

Early life “luck” among competitive male mice leads to competitive advantage overall

2025-01-02

Early life "luck" plays a pivotal role in shaping individuality and success, particularly for males, according to a new study in mice. In male animals, competitive social dynamics amplified small initial differences into lifelong disparities in fitness. The findings highlight parallels between biological competition and societal inequalities and they demonstrate how chance events can drive divergent outcomes even among genetically identical individuals. Contingency (colloquially, “luck”) refers to the role of chance in shaping outcomes. It is a critical factor in both biological and social sciences, ...

A closer look at the role of rare germline structural variants in pediatric solid tumors

2025-01-02

Largescale changes in the genome inherited from parents are significant risk factors for pediatric solid tumors, such as Ewing sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and osteosarcoma, according to a new study. The findings, which highlight the role of germline structural variants (SVs) in early genome instability, provide new insights into the genetic underpinnings of pediatric cancers and open doors for improved diagnostic and treatment strategies. Unlike adult cancers, which often result from environmental factors or DNA damage built up over time, ...

Genetics of alternating sexes in walnuts

2025-01-02

The genetics behind the alternating sexes of walnut trees has been revealed by biologists at the University of California, Davis. The research, published Jan. 3 in Science, reveals a mechanism that has been stable in walnuts and their ancestors going back 40 million years — and which has some parallels to sex determination in humans and other animals.

Flowering plants have many ways to avoid pollinating themselves. Some do this by structuring flowers to make self-pollination difficult; some species have separate “male” and “female” plants. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

[Press-News.org] Detecting disease with only a single moleculeNanopore-based sensors could transform diagnostics