(Press-News.org) Birds are the undisputed champions of epic travel—but they are not the only long-haul fliers. A handful of bats are known to travel thousands of kilometers in continental migrations across North America, Europe, and Africa. The behavior is rare and difficult to observe, which is why long-distance bat migration has remained an enigma. Now, scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior (MPI-AB) have studied 71 common noctule bats on their spring migration across the European continent, providing a leap in understanding this mysterious behavior. Ultra-lightweight, intelligent sensors attached to bats uncovered a strategy used by the tiny mammals for travel: they surf the warm fronts of storms to fly further with less energy. The study is published in Science.

“The sensor data are amazing!” says first author Edward Hurme, a postdoctoral researcher at MPI-AB and the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behaviour at the University of Konstanz. “We don’t just see the path that bats took, we also see what they experienced in the environment as they migrated. It’s this context that gives us insight into the crucial decisions that bats made during their costly and dangerous journeys.”

Using novel sensor technology, the study examined a portion of the total migration of noctules, which scientists estimate to be around 1600-kilometers. “We are still far from observing the complete yearly cycle of long-distance bat migration,” says Hurme. “The behavior is still a black box, but at least we have a tool that has shed some light.”

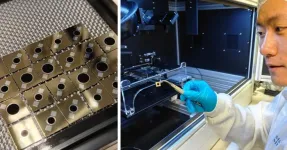

The study’s tracking device was developed by engineers at MPI-AB. Weighing only five percent of the bat’s total body mass, the tiny tag includes multiple sensors that recorded activity levels of bats and temperature of the surrounding air. Normally, scientists would need to find tagged animals and be close enough to download such detailed data. But the study’s tag compressed the data, totaling 1440 daily sensor measurements, into a 12-byte message that was transmitted via a novel long-range network. “The tags communicate with us from wherever the bats are because they have coverage across Europe much like a cell phone network,” says senior author Timm Wild, who led the development of the ICARUS-TinyFoxBatt tag in his Animal-borne Sensor Networks group at MPI-AB.

The team deployed the tags on common noctules, a bat that is wide-spread in Europe and one of only four bat species known to migrate across the continent. Every spring for three years, the scientists attached tags on common noctules in Switzerland, focusing exclusively on females which are more migratory than males. Females spend summers in northern Europe and winters in a range of southerly locations where they hibernate until spring.

The tags collected data for up to four weeks as the female noctules migrated back northeast, revealing trajectories far more variable than previously thought. “There is no migration corridor,” says senior author Dina Dechmann from MPI-AB. “We had assumed that bats were following a unified path, but we now see they are moving all over the landscape in a general northeast direction.”

The scientists teased apart the data to distinguish hour-long feeding flights from the much longer migratory flights, finding that noctules can migrate almost 400 kilometers in a single night—breaking the known record for the species. Bats alternated their migratory flights with frequent stops, likely because they needed to feed continuously. “Unlike migratory birds, bats don’t gain weight in preparation for migration,” says Dechmann. “They need to refuel every night, so their migration has a hopping pattern rather than a straight shot.”

The authors then detected a striking pattern. “On certain nights, we saw an explosion of departures that looked like bat fireworks,” says Hurme. “We needed to figure out what all these bats were responding to on those particular nights.”

They found that these migration waves could be explained by changes in weather. Bats left on nights when air pressure dropped and temperature spiked; in other words, the bats left before incoming storms. “They were riding storm fronts, using the support of warm tailwinds,” says Hurme. The tag’s sensors that measured activity levels further showed that bats used less energy flying on these nights of warm wind, confirming that the tiny mammals were harvesting invisible energy from the environment to power their continental flights. “It was known that birds use wind support during migration, and now we see that bats do too,” he adds.

The implications of these findings go beyond biological insight into this understudied behavior. Migratory bats are threatened by human activity, in particular wind turbines which are the cause of frequent collisions. Knowing where bats will be migrating, and when, could help to prevent deaths.

“Before this study, we didn’t know what triggered bats to start migrating,” says Hurme. “More studies like this will pave the way for a system to forecast bat migration. We can be stewards of bats, helping wind farms to turn off their turbines on nights when bats are streaming through. This is just a small glimpse of what we will find if we all keep working to open that black box.”

END

Bats surf storm fronts during continental migration

Scientists use ultra-light sensors connected “like cell phones” across Europe to study how bats migrate over the continent

2025-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Canadian forests are more prone to severe wildfires in recent decades

2025-01-02

Climate change is driving more intense wildfires in Canada, according to a new modeling study, with fuel aridity and rising temperatures amplifying burn severity, particularly over the last several decades. The findings underscore the growing impact of climate change on wildfire behavior, with the most severe effects concentrated in Canada’s northern forests. Fueled by ongoing climate change, Canada – one of the most forested and fire-prone regions in the Northern Hemisphere – is grappling with increasingly severe and prolonged wildfire seasons. ...

Secrets of migratory bats: They “surf” storm front winds to save energy

2025-01-02

A species of migrating bat “surfs” the warm winds of incoming storm fronts to conserve energy, according to a study that used tags to track the tiny animals on their long journeys across central Europe. The findings offer new insights into how weather, physiology, and environmental factors shape bats’ seasonal migration patterns. While bird migration is well-documented and studied, this is not the case for seasonal migration of bats – particularly the few long-distance, migratory species. These nocturnal travelers face substantial challenges, ...

Early life “luck” among competitive male mice leads to competitive advantage overall

2025-01-02

Early life "luck" plays a pivotal role in shaping individuality and success, particularly for males, according to a new study in mice. In male animals, competitive social dynamics amplified small initial differences into lifelong disparities in fitness. The findings highlight parallels between biological competition and societal inequalities and they demonstrate how chance events can drive divergent outcomes even among genetically identical individuals. Contingency (colloquially, “luck”) refers to the role of chance in shaping outcomes. It is a critical factor in both biological and social sciences, ...

A closer look at the role of rare germline structural variants in pediatric solid tumors

2025-01-02

Largescale changes in the genome inherited from parents are significant risk factors for pediatric solid tumors, such as Ewing sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and osteosarcoma, according to a new study. The findings, which highlight the role of germline structural variants (SVs) in early genome instability, provide new insights into the genetic underpinnings of pediatric cancers and open doors for improved diagnostic and treatment strategies. Unlike adult cancers, which often result from environmental factors or DNA damage built up over time, ...

Genetics of alternating sexes in walnuts

2025-01-02

The genetics behind the alternating sexes of walnut trees has been revealed by biologists at the University of California, Davis. The research, published Jan. 3 in Science, reveals a mechanism that has been stable in walnuts and their ancestors going back 40 million years — and which has some parallels to sex determination in humans and other animals.

Flowering plants have many ways to avoid pollinating themselves. Some do this by structuring flowers to make self-pollination difficult; some species have separate “male” and “female” plants. ...

Building better infrared sensors

2025-01-02

Detecting infrared light is critical in an enormous range of technologies, from remote controls to autofocus systems to self-driving cars and virtual reality headsets. That means there would be major benefits from improving the efficiency of infrared sensors, such as photodiodes.

Researchers at Aalto University have developed a new type of infrared photodiode that is 35% more responsive at 1.55 µm, the key wavelength for telecommunications, compared to other germanium-based components. Importantly, this new device can be manufactured using current production techniques, making it highly practical for adoption.

‘It ...

Increased wildfire activity may be a feature of past periods of abrupt climate change, study finds

2025-01-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new study investigating ancient methane trapped in Antarctic ice suggests that global increases in wildfire activity likely occurred during periods of abrupt climate change throughout the last Ice Age.

The study, just published in the journal Nature, reveals increased wildfire activity as a potential feature of these periods of abrupt climate change, which also saw significant shifts in tropical rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuations around the world.

“This study showed that the planet experienced these short, ...

Dogs trained to sniff out spotted lanternflies could help reduce spread

2025-01-02

Media note: Video of the Labrador retriever, Dia, in action is available for download, along with photos of the dogs and egg masses, here.

ITHACA, N.Y. - Growers and conservationists have a new weapon to detect invasive spotted lanternflies early and limit their spread: dogs trained to sniff out egg masses that overwinter in vineyards and forests.

A Cornell University study found that trained dogs – a Labrador retriever and a Belgian Malinois – were better than humans at detecting egg masses in forested areas near vineyards, while people spotted them better than the dogs in vineyards.

The spotted lanternfly, which was first ...

New resource available to help scientists better classify cancer subtypes

2025-01-02

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (Jan. 2, 2025) — A multi-institutional team of scientists has developed a free, publicly accessible resource to aid in classification of patient tumor samples based on distinct molecular features identified by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network.

The resource comprises classifier models that can accelerate the design of cancer subtype-specific test kits for use in clinical trials and cancer diagnosis. This is an important advance because tumors belonging to different subtypes may vary in their response to cancer therapies.

The resource is the first of its kind to bridge the gap between TCGA’s immense data library ...

What happens when some cells are more like Dad than Mom

2025-01-02

NEW YORK, NY--New work by Columbia researchers has turned a textbook principle of genetics on its head and revealed why some people who carry disease-causing genes experience no symptoms.

Every biology student learns that each cell in our body (except sperm and eggs) contains two copies of each gene, one from each parent, and each copy plays an equal part in the cell.

The new study shows that some cells are often biased when it comes to some genes and inactivate one parent’s copy. The phenomenon was discovered about a decade ago, but ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

In football players with repeated head impacts, inflammation related to brain changes

Being an early bird, getting more physical activity linked to lower risk of ALS

The Lancet: Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Black Americans face increasingly higher risk of gun homicide death than White Americans

Flagging claims about cancer treatment on social media as potentially false might help reduce spreading of misinformation, per online experiment with 1,051 US adults

Yawns in healthy fetuses might indicate mild distress

Conservation agriculture, including no-dig, crop-rotation and mulching methods, reduces water runoff and soil loss and boosts crop yield by as much as 122%, in Ethiopian trial

Tropical flowers are blooming weeks later than they used to through climate change

Risk of whale entanglement in fishing gear tied to size of cool-water habitat

Climate change could fragment habitat for monarch butterflies, disrupting mass migration

Neurosurgeons are really good at removing brain tumors, and they’re about to get even better

Almost 1-in-3 American adolescents has diabetes or prediabetes, with waist-to-height ratio the strongest independent predictor of prediabetes/diabetes, reveals survey of 1,998 adolescents (10-19 years

Researchers sharpen understanding of how the body responds to energy demands from exercise

New “lock-and-key” chemistry

Benzodiazepine use declines across the U.S., led by reductions in older adults

How recycled sewage could make the moon or Mars suitable for growing crops

Don’t Panic: ‘Humanity’s Last Exam’ has begun

A robust new telecom qubit in silicon

Vertebrate paleontology has a numbers problem. Computer vision can help

[Press-News.org] Bats surf storm fronts during continental migrationScientists use ultra-light sensors connected “like cell phones” across Europe to study how bats migrate over the continent