(Press-News.org) The genetics behind the alternating sexes of walnut trees has been revealed by biologists at the University of California, Davis. The research, published Jan. 3 in Science, reveals a mechanism that has been stable in walnuts and their ancestors going back 40 million years — and which has some parallels to sex determination in humans and other animals.

Flowering plants have many ways to avoid pollinating themselves. Some do this by structuring flowers to make self-pollination difficult; some species have separate “male” and “female” plants. Others separate their male and female flowers in time. Trees in the family which includes walnut, hickory and pecan take this one step further. A walnut tree produces flowers of one sex, then the other in the same season, but trees differ in which one comes first. Individual trees are consistently “male-first” or “female-first” in flowering, something noted by Charles Darwin in 1877. In the 1980s a UC Davis graduate student, Scott Gleeson, noted that this phenotype was controlled by a single genetic locus.

“Walnuts and pecans have a temporal dimorphism where they alternate male and female flowering through the season,” said Jeff Groh, graduate student in population biology at UC Davis and first author on the paper. “It’s been known since the 1800s but hasn’t been understood at the molecular level before.”

This occurs in both domesticated walnuts and wild relatives, like Northern California black walnut. In wild species, the ratio of male-first to female-first trees is almost 1:1.

Groh and his doctoral advisor, Professor Graham Coop of the Department of Evolution and Ecology, made use of data from UC Davis’ walnut breeding program and also tracked flowering in native Northern California black walnut trees growing around the UC Davis campus. Assigning them to male-first or female-first groups, the researchers sequenced their genomes and identified sequences associated with the trait.

Same mechanism, different genes

In walnuts, they found two variants of a gene linked to female-first or male-first flowering. This DNA polymorphism appears in at least nine species of walnut and has been stable for almost 40 million years.

“It’s pretty atypical to maintain variation over such a long time,” Groh said. In this case, the two flowering types balance each other. If one flowering type becomes more common in the population than the other, the less common type gains a mating advantage, so it becomes more common. This pushes the system to a 50:50 equilibrium and maintains genetic variation.

Pecans, Groh found, also have a balanced genetic polymorphism determining flowering order, but in a different part of the genome to walnut. The pecan polymorphism appears to be older than in walnut, at over 50 million years.

How did walnuts and pecans, which are related, arrive at the same flowering mechanism through quite different genes?

It could be that the ancestors of walnuts and pecans converged on similar solutions as they evolved. But it’s also possible that this time-separated flowering system appeared even longer ago in this family, about 70 million years ago, but over time the exact genetic mechanisms to achieve it have changed.

Intriguingly, this is similar to the way animal sex chromosomes work, with two structural variants (X and Y chromosomes in humans and other mammals) kept roughly in balance.

“There’s a clear parallel to a common mode of sex determination,” Groh said.

Additional authors on the paper are: Diane Vik, Matthew Davis, J. Grey Monroe, Kristian Stevens, Patrick Brown and Charles Langley, all at UC Davis. Funding was provided by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, the Davis Botanical Society and the American Society of Plant Taxonomists. This work made use of trees from the UC Davis Putah Creek Riparian Reserve; Gene Cripe of Turlock, Calif.; USDA Wolfskill Experimental Orchard; Sonoma Botanical Garden and the UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley.

END

Genetics of alternating sexes in walnuts

2025-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

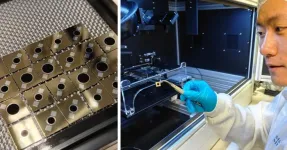

Building better infrared sensors

2025-01-02

Detecting infrared light is critical in an enormous range of technologies, from remote controls to autofocus systems to self-driving cars and virtual reality headsets. That means there would be major benefits from improving the efficiency of infrared sensors, such as photodiodes.

Researchers at Aalto University have developed a new type of infrared photodiode that is 35% more responsive at 1.55 µm, the key wavelength for telecommunications, compared to other germanium-based components. Importantly, this new device can be manufactured using current production techniques, making it highly practical for adoption.

‘It ...

Increased wildfire activity may be a feature of past periods of abrupt climate change, study finds

2025-01-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new study investigating ancient methane trapped in Antarctic ice suggests that global increases in wildfire activity likely occurred during periods of abrupt climate change throughout the last Ice Age.

The study, just published in the journal Nature, reveals increased wildfire activity as a potential feature of these periods of abrupt climate change, which also saw significant shifts in tropical rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuations around the world.

“This study showed that the planet experienced these short, ...

Dogs trained to sniff out spotted lanternflies could help reduce spread

2025-01-02

Media note: Video of the Labrador retriever, Dia, in action is available for download, along with photos of the dogs and egg masses, here.

ITHACA, N.Y. - Growers and conservationists have a new weapon to detect invasive spotted lanternflies early and limit their spread: dogs trained to sniff out egg masses that overwinter in vineyards and forests.

A Cornell University study found that trained dogs – a Labrador retriever and a Belgian Malinois – were better than humans at detecting egg masses in forested areas near vineyards, while people spotted them better than the dogs in vineyards.

The spotted lanternfly, which was first ...

New resource available to help scientists better classify cancer subtypes

2025-01-02

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (Jan. 2, 2025) — A multi-institutional team of scientists has developed a free, publicly accessible resource to aid in classification of patient tumor samples based on distinct molecular features identified by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network.

The resource comprises classifier models that can accelerate the design of cancer subtype-specific test kits for use in clinical trials and cancer diagnosis. This is an important advance because tumors belonging to different subtypes may vary in their response to cancer therapies.

The resource is the first of its kind to bridge the gap between TCGA’s immense data library ...

What happens when some cells are more like Dad than Mom

2025-01-02

NEW YORK, NY--New work by Columbia researchers has turned a textbook principle of genetics on its head and revealed why some people who carry disease-causing genes experience no symptoms.

Every biology student learns that each cell in our body (except sperm and eggs) contains two copies of each gene, one from each parent, and each copy plays an equal part in the cell.

The new study shows that some cells are often biased when it comes to some genes and inactivate one parent’s copy. The phenomenon was discovered about a decade ago, but ...

CAR-T cells hold memories of past encounters

2025-01-02

AURORA, Colo. (Jan. 2, 2025) - Researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have discovered that some CAR-T cells engineered to fight cancer and other conditions carry the memory of past encounters with bacteria, viruses and other antigens within them, a finding that may allow scientists to manufacture the cells in more precise and targeted ways.

The study, published today in the journal Nature Immunology, focused on chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, an effective therapy against ...

Quantity over quality? Different bees are attracted to different floral traits

2025-01-02

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — When it comes to deciding where they’re going to get their next meal, different species of bees may be attracted to different flower traits, according to a study led by researchers at Penn State and published in PNAS Nexus.

The study focused on two species of solitary bees: the horned-face bee, which helps pollinate crops like apples and blueberries, and the alfalfa leafcutting bee, which pollinates alfalfa.

The researchers found that the horned-face bees tended to prefer plants with a large number of flowers — for them, quantity was most important. ...

Cancer-preventing topical immunotherapy trains the immune system to fight precancers

2025-01-02

A new study by investigators from Mass General Brigham uncovers how a novel immunotherapy prevents squamous cell carcinoma, with benefits lasting five years after treatment. This therapy is the first to activate specific components of the adaptive immune system, particularly CD4+ T helper cells, which are not known to be involved in traditional cancer treatments. This work highlights the potential for similar immunotherapies to prevent other cancers throughout the body. Results are published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

“One of the unique challenges with squamous cell carcinoma is that individuals who develop it are at an increased risk of developing multiple new ...

Blood test can predict how long vaccine immunity will last, Stanford Medicine-led study shows

2025-01-02

When children receive their second measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, around the time they start kindergarten, they gain protection against all three viruses for all or most of their lives. Yet the effectiveness of an influenza vaccine given in October starts to wane by the following spring.

Scientists have long been stymied by why some vaccines can coax the body to produce antibodies for decades, while others last mere months. Now, a study led by researchers at Stanford Medicine has shown that variation in vaccine durability can, in part, be pinned on a surprising type ...

The nose knows: Nasal swab detects asthma type in kids

2025-01-02

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have developed a nasal swab test for kids that diagnoses specific asthma subtype, or endotype. This non-invasive approach could help clinicians prescribe medications more precisely and pave the way for research toward better treatments for lesser-studied asthma types, which have been difficult to diagnose accurately until now.

Published today in JAMA, the findings are based on data from three independent U.S.-based studies that focused on Puerto Rican and African American youths, who have higher rates of asthma and are more likely to die from the disease than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

“Asthma ...