(Press-News.org) An ancient brain circuit, which enables the eyes to reflexively rotate up as the body tilts down, tunes itself early in life as an animal develops, a new study finds.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the study revolves around how vertebrates, which includes humans and animals spanning evolution from primitive fish to mammals, stabilize their gaze as they move. To do so they use a brain circuit that turns any shifts in orientation sensed by the balance (vestibular) system in their ears into an instant counter-movement by their eyes.

Called the vestibulo-ocular reflex, the circuit enables the stable perception of surroundings. When it is broken — by trauma, stroke, or a genetic condition — a person may feel like the world bounces around every time their head or body moves. In adult vertebrates, it and other brain circuits are tuned by feedback from the senses (vision and balance organs). The current study authors were surprised to find that, in contrast, sensory input was not necessary for maturation of the reflex circuit in newborns.

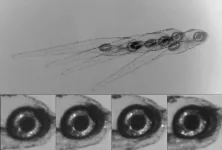

Published online January 2 in the journal Science, the study featured experiments done in zebrafish larvae, which have a similar gaze stabilizing reflex to the one in humans. Further, zebrafish are transparent, so researchers litterally watched brain cells called neurons mature to understand the changes that let a newborn fish rotate its eyes up appropriately as its body tilts down (or its eyes down as its body tilts up).

“Discovering how vestibular reflexes come to be may help us find new ways to counter pathologies that affect balance or eye movements," says study senior author David Schoppik, PhD, associate professor in the Departments of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, Neuroscience & Physiology, and the Neuroscience Institute, at NYU Langone Health.

Split-Second Tilts

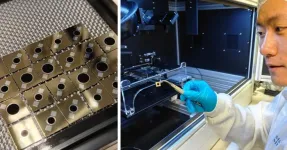

To test the long-held assumption that the reflex is tuned by visual feedback, the research team invented an apparatus to elicit the reflex by tilting and monitoring the eyes of zebrafish that were blind since birth. The team observed that the ability of the fish to counterrotate their eyes after tilt was comparable to larvae that could see.

Although past studies established that sensory input helps animals learn to move properly in their environment, the new work suggests that such tuning of the vestibulo-ocular reflex comes into play only after the reflex has fully matured. Remarkably, another set of experiments showed that the reflex circuit also reaches maturity during development without input from a gravity-sensing vestibular organ called the utricle.

Because the vestibulo-ocular reflex could mature without sensory feedback, the researchers theorized that the slowest-maturing part of the brain circuit must set the pace for the development of the reflex. To find the rate-limiting part, the research team measured the response of neurons throughout development as they gave zebrafish split-second body tilts.

The researchers found that central and motor neurons in the circuit showed mature responses before the reflex had finished developing. Consequently, the slowest part of the circuit to mature could not be in the brain as long assumed, but was found instead to be at the neuromuscular junction — the signaling space between motor neurons and the muscle cells that move the eye. A series of experiments revealed that only the pace of maturation of the junction matched the rate at which fish improved their ability to counter-rotate their eyes.

Moving forward, Dr. Schoppik’s team is funded to study their newly detailed circuit in the context of human disorders. Ongoing work explores how failures of motor neuron and neuromuscular junction development lead to disorders of the ocular motor system, including a common misalignment of the eyes called strabismus (a.k.a., lazy eye, crossed eyes).

Just upstream of motor neurons in the vestibulo-ocular circuit are interneurons that sculpt incoming sensory information and integrate what the eyes see with balance organs. Another of Dr. Schoppik’s grants seeks to better understand how the function of such cells is disrupted as balance circuits develop, with the goal of helping the five percent of children in the U.S. wrestling with some form of balance problem.

“Understanding the basic principles of how vestibular circuits emerge is a prerequisite to solving not only balance problems, but also brain disorders of development,” says first study author Paige Leary, PhD. She was a graduate student in Dr. Schoppik’s lab who led the study but has since left the institution.

Along with Drs. Schoppik and Leary, study authors from the departments of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, Neuroscience & Physiology, and the Neuroscience Institute, at NYU Langone Health included Celine Bellegarda, Cheryl Quainoo, Dena Goldblatt, and Basak Rosti. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders grants R01DC017489 and F31DC020910, and by National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant F99NS129179. The National Science Foundation also supported the study through graduate research fellowship DGE2041775.

END

Newborn brain circuit stabilizes gaze

Discovery may guide future research into eye movement and balance disorders

2025-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bats surf storm fronts during continental migration

2025-01-02

Birds are the undisputed champions of epic travel—but they are not the only long-haul fliers. A handful of bats are known to travel thousands of kilometers in continental migrations across North America, Europe, and Africa. The behavior is rare and difficult to observe, which is why long-distance bat migration has remained an enigma. Now, scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior (MPI-AB) have studied 71 common noctule bats on their spring migration across the European continent, providing a leap in understanding this mysterious behavior. Ultra-lightweight, intelligent sensors attached ...

Canadian forests are more prone to severe wildfires in recent decades

2025-01-02

Climate change is driving more intense wildfires in Canada, according to a new modeling study, with fuel aridity and rising temperatures amplifying burn severity, particularly over the last several decades. The findings underscore the growing impact of climate change on wildfire behavior, with the most severe effects concentrated in Canada’s northern forests. Fueled by ongoing climate change, Canada – one of the most forested and fire-prone regions in the Northern Hemisphere – is grappling with increasingly severe and prolonged wildfire seasons. ...

Secrets of migratory bats: They “surf” storm front winds to save energy

2025-01-02

A species of migrating bat “surfs” the warm winds of incoming storm fronts to conserve energy, according to a study that used tags to track the tiny animals on their long journeys across central Europe. The findings offer new insights into how weather, physiology, and environmental factors shape bats’ seasonal migration patterns. While bird migration is well-documented and studied, this is not the case for seasonal migration of bats – particularly the few long-distance, migratory species. These nocturnal travelers face substantial challenges, ...

Early life “luck” among competitive male mice leads to competitive advantage overall

2025-01-02

Early life "luck" plays a pivotal role in shaping individuality and success, particularly for males, according to a new study in mice. In male animals, competitive social dynamics amplified small initial differences into lifelong disparities in fitness. The findings highlight parallels between biological competition and societal inequalities and they demonstrate how chance events can drive divergent outcomes even among genetically identical individuals. Contingency (colloquially, “luck”) refers to the role of chance in shaping outcomes. It is a critical factor in both biological and social sciences, ...

A closer look at the role of rare germline structural variants in pediatric solid tumors

2025-01-02

Largescale changes in the genome inherited from parents are significant risk factors for pediatric solid tumors, such as Ewing sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and osteosarcoma, according to a new study. The findings, which highlight the role of germline structural variants (SVs) in early genome instability, provide new insights into the genetic underpinnings of pediatric cancers and open doors for improved diagnostic and treatment strategies. Unlike adult cancers, which often result from environmental factors or DNA damage built up over time, ...

Genetics of alternating sexes in walnuts

2025-01-02

The genetics behind the alternating sexes of walnut trees has been revealed by biologists at the University of California, Davis. The research, published Jan. 3 in Science, reveals a mechanism that has been stable in walnuts and their ancestors going back 40 million years — and which has some parallels to sex determination in humans and other animals.

Flowering plants have many ways to avoid pollinating themselves. Some do this by structuring flowers to make self-pollination difficult; some species have separate “male” and “female” plants. ...

Building better infrared sensors

2025-01-02

Detecting infrared light is critical in an enormous range of technologies, from remote controls to autofocus systems to self-driving cars and virtual reality headsets. That means there would be major benefits from improving the efficiency of infrared sensors, such as photodiodes.

Researchers at Aalto University have developed a new type of infrared photodiode that is 35% more responsive at 1.55 µm, the key wavelength for telecommunications, compared to other germanium-based components. Importantly, this new device can be manufactured using current production techniques, making it highly practical for adoption.

‘It ...

Increased wildfire activity may be a feature of past periods of abrupt climate change, study finds

2025-01-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new study investigating ancient methane trapped in Antarctic ice suggests that global increases in wildfire activity likely occurred during periods of abrupt climate change throughout the last Ice Age.

The study, just published in the journal Nature, reveals increased wildfire activity as a potential feature of these periods of abrupt climate change, which also saw significant shifts in tropical rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuations around the world.

“This study showed that the planet experienced these short, ...

Dogs trained to sniff out spotted lanternflies could help reduce spread

2025-01-02

Media note: Video of the Labrador retriever, Dia, in action is available for download, along with photos of the dogs and egg masses, here.

ITHACA, N.Y. - Growers and conservationists have a new weapon to detect invasive spotted lanternflies early and limit their spread: dogs trained to sniff out egg masses that overwinter in vineyards and forests.

A Cornell University study found that trained dogs – a Labrador retriever and a Belgian Malinois – were better than humans at detecting egg masses in forested areas near vineyards, while people spotted them better than the dogs in vineyards.

The spotted lanternfly, which was first ...

New resource available to help scientists better classify cancer subtypes

2025-01-02

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (Jan. 2, 2025) — A multi-institutional team of scientists has developed a free, publicly accessible resource to aid in classification of patient tumor samples based on distinct molecular features identified by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network.

The resource comprises classifier models that can accelerate the design of cancer subtype-specific test kits for use in clinical trials and cancer diagnosis. This is an important advance because tumors belonging to different subtypes may vary in their response to cancer therapies.

The resource is the first of its kind to bridge the gap between TCGA’s immense data library ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

New study finds deep ocean microbes already prepared to tackle climate change

ARLIS partners with industry leaders to improve safety of quantum computers

Modernization can increase differences between cultures

Cannabis intoxication disrupts many types of memory

Heat does not reduce prosociality

Advancing brain–computer interfaces for rehabilitation and assistive technologies

Detecting Alzheimer's with DNA aptamers—new tool for an easy blood test

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal study develops radiomics model to predict secondary decompressive craniectomy

New molecular switch that boosts tooth regeneration discovered

Jeonbuk National University researchers track mineral growth on bioorganic coatings in real time at nanoscale

Convergence in the Canopy: Why the Gracixalus weii treefrog sounds like a songbird

Subway systems are uncomfortably hot — and worsening

Granular activated carbon-sorbed PFAS can be used to extract lithium from brine

How AI is integrated into clinical workflow lowers medical liability perception

New biotech company to accelerate treatments for heart disease

One gene makes the difference: research team achieves breakthrough in breeding winter-hardy faba beans

Predicting brain health with a smartwatch

How boron helps to produce key proteins for new cancer therapies

Writing the catalog of plasma membrane repair proteins

A comprehensive review charts how psychiatry could finally diagnose what it actually treats

[Press-News.org] Newborn brain circuit stabilizes gazeDiscovery may guide future research into eye movement and balance disorders