(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA (January 14, 2025)—Like all cancers, bladder cancer develops when abnormal cells start to multiply out of control. But what if we could put a lid on their growth?

Previous studies showed that a protein called PIN1 helps cancers initiate and progress, but its exact role in tumor development has remained unclear. Now, cancer biologists at the Salk Institute have discovered that PIN1 is a significant driver of bladder cancer and revealed that it works by triggering the synthesis of cholesterol—a membrane lipid essential for cancer cells to grow.

After mapping out the molecular pathway between PIN1 and cholesterol, the researchers developed an effective treatment regimen that largely halted tumor growth in their mouse model of cancer. The therapy consists of two drugs: a PIN1 inhibitor called sulfopin, an experimental drug not yet tested in humans, and simvastatin, a statin that is already used in humans for lowering cholesterol levels to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

The findings were published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, on January 14, 2025.

“We’re excited to be the first to identify PIN1’s role in bladder cancer and to describe the mechanism it uses to drive tumor growth,” says senior author Tony Hunter, American Cancer Society professor and holder of the Renato Dulbecco Chair at Salk. “Given the high costs, morbidity, and mortality rates for bladder cancer, we’re especially thrilled to discover that targeting the cholesterol pathway with this therapeutic combination was so effective in suppressing bladder tumor growth in mice, and we hope to see this approach explored in a future clinical trial, once a PIN1 inhibitor is approved for clinical use.”

Bladder cancer is one of the most diagnosed cancers worldwide and the fourth most common cancer among men. It poses a serious threat to public health, as most cases result in either expensive, lifelong treatment, or rapid progression and mortality.

Hunter’s lab had originally discovered PIN1 in 1996 as a part of its work on phosphorylation, a process in which phosphate molecules are tacked onto proteins to change their structure and function. The lab showed that PIN1 is an enzyme that can recognize a protein when a phosphate is added to the amino acid serine while it’s next to the amino acid proline. PIN1 then changes that protein’s shape.

Phosphorylation of proteins at serine residues next to prolines is known to be a major signaling mechanism controlling cell proliferation and malignant transformation, and its dysregulation causes human cancers. PIN1 can target these phosphorylated areas and instigate structural and functional changes to the protein. Still, it’s been unclear exactly how this PIN1 activity contributes to tumor formation or which proteins PIN1 might be interacting with in bladder cancer cells.

In search of answers, the team compared normal human bladder cells with bladder cancer cells, in culture dishes and implanted in mice.

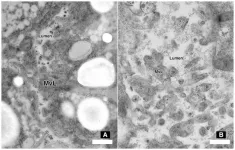

First, they demonstrated that PIN1 expression was higher in bladder cancer cells—specifically in the specialized tissue layer that lines the inside of the urinary tract, called the urothelium. Then, they used genetic scissors to eliminate the PIN1 gene in the cancer cells. Without PIN1, they saw fewer cancerous cells develop, and those that did develop migrated less aggressively within and beyond the urothelium.

These findings indicated that PIN1 was contributing to the development of bladder cancer, but how?

The researchers returned to the cells that were missing PIN1 and looked to see if any other biological processes had been altered. Surprisingly, they found that one of the most affected pathways was the cholesterol synthesis pathway, mediated by a protein called SREBP2. Without PIN1, the bladder cells contained much lower levels of cholesterol.

“Cancer cells need a lot of cholesterol to accomplish their trademark excess growth,” says first author Xue Wang, a postdoctoral researcher in Hunter’s lab. “Our findings show that PIN1 plays an important role in cholesterol production, and removing it leads to lower cholesterol and therefore less out-of-control tumor growth.”

Through a series of experiments, the researchers confirmed that PIN1 was working with the SREBP2 protein to stimulate cholesterol production. Removing PIN1 effectively put a lid on the cancer’s fuel supply, but reinstating PIN1 reversed those anti-cancer effects. Without intervention, the high level of PIN1 in bladder cancer assists in tumor growth and metastasis.

How can we stop PIN1? One obvious answer is to inhibit the protein itself, but it’s also possible to inhibit an enzyme in the cholesterol pathway that PIN1 stimulates. One class of drugs, called statins, is already very widely used to control cholesterol levels. Statins work by blocking a protein in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway called HMGCR. The idea was to attack the cholesterol pathway from two angles by combining simvastatin, a widely prescribed statin, to block HMGCR, and sulfopin to disable PIN1 and prevent its activation of SREBP2, thus drastically reducing the ability of the bladder cancer cells to make cholesterol.

When the researchers treated the mice with bladder cancer tumors with the PIN1 inhibitor sulfopin and the HMGCR inhibitor simvastatin, they found the combination suppressed cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth—importantly, the two worked better in tandem than as individual treatments.

“This is likely just one of many roles that PIN1 plays in cancers,” says Hunter. “What’s exciting about this discovery, though, is that statins are already in human use to prevent cardiovascular disease, and our work suggests an opportunity to use statins in combination with other drugs for bladder cancer therapy. And beyond this, we’ll continue to study whether PIN1 plays a similar role in other cancers, so our findings can hopefully improve lives regardless of cancer type.”

Not only did the team confirm PIN1’s role in bladder cancer progression, they also connected PIN1 to cholesterol biosynthesis and created viable treatment solutions to improve treatment outcomes.

Other authors include Yuan Sui and Jill Meisenhelder of Salk, Derrick Lee of UC San Diego, and Haibo Xu of Shenzhen University in China.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CCSG P30CA023100, CCSG CA014159, 5 R35 CA242443) and a Pioneer Fund Postdoctoral Scholar Award.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology, and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge. Learn more at www.salk.edu.

END

Putting a lid on excess cholesterol to halt bladder cancer cell growth

Salk researchers discover novel targets for bladder cancer therapeutics and demonstrate that a new combination of existing drugs, including statins, blocks tumor growth in mice

2025-01-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genetic mutation linked to higher SARS-CoV-2 risk

2025-01-14

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Researchers have identified a novel genetic risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection, providing new insights into the virus’ ability to invade human cells. SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that spreads COVID-19.

The study, led by immunologist Declan McCole at the University of California, Riverside, shows that a loss-of-function variant in the phosphatase gene PTPN2, commonly associated with autoimmune diseases, can increase expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2, making cells more susceptible to viral invasion.

A loss-of-function ...

UC Irvine, Columbia University researchers invent soft, bioelectronic sensor implant

2025-01-14

Irvine, Calif., Jan. 14, 2025 — Researchers at the University of California, Irvine and New York’s Columbia University have embedded transistors in a soft, conformable material to create a biocompatible sensor implant that monitors neurological functions through successive phases of a patient’s development.

In a paper published recently in Nature Communications, the UC Irvine scientists describe their construction of complementary, internal, ion-gated, organic electrochemical transistors that are more amenable ...

Harnessing nature to defend soybean roots

2025-01-14

The microscopic soybean cyst nematode (SCN) may be small, but it has a massive impact. This pest latches onto soybean roots, feeding on their nutrients and leaving a trail of destruction that costs farmers billions in yield losses each year. Unfortunately, current methods to combat SCN are faltering as the pest grows resistant to traditional controls. But new research is now offering a glimmer of hope.

A collaborative team of scientists from BASF Agricultural Solutions and the Advanced Bioimaging Laboratory at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center are working on a potential solution: ...

Yes, college students gain holiday weight too—but in the form of muscle not fat

2025-01-14

With the holidays behind us, many Americans are seeing the numbers on the scale go up a pound or two. In fact, data shows that many American midlife and older adults gain 1 to 1.5 pounds over the November through January holiday period. Though not harmful on its own, even a small amount of holiday weight gain in the form of fat can negatively affect health. People often fail to lose the extra weight, which leads to significant cumulative weight gain over the years and contributes to health concerns.

Based on new research, we now know that college students gain the same amount of weight as older ...

Beach guardians: How hidden microbes protect coastal waters in a changing climate

2025-01-14

A hidden world teeming with life lies below beach sands. New Stanford-led research sheds light on how microbial communities in coastal groundwater respond to infiltrating seawater. The study, published Dec. 22 in Environmental Microbiology, reveals the diversity of microbial life inhabiting these critical ecosystems and what might happen if they are inundated by rising seas.

“Beaches can act as a filter between land and sea, processing groundwater and associated chemicals before they reach the ocean,” said study co-first author Jessica Bullington, a Ph.D. student in Earth system science in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “Understanding ...

Rice researchers unlock new insights into tellurene, paving the way for next-gen electronics

2025-01-14

HOUSTON – (Jan. 14, 2025) – To describe how matter works at infinitesimal scales, researchers designate collective behaviors with single concepts ⎯ like calling a group of birds flying in sync a “flock” or “murmuration.” Known as quasiparticles, the phenomena these concepts refer to could be the key to next-generation technologies.

In a recent study published in Science Advances, a team of researchers led by Shengxi Huang, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and materials science and nanoengineering at Rice, describe how one such type of quasiparticle ⎯ polarons ⎯ behaves in tellurene, a nanomaterial first synthesized ...

New potential treatment for inherited blinding disease retinitis pigmentosa

2025-01-14

Two new compounds may be able to treat retinitis pigmentosa, a group of inherited eye diseases that cause blindness. The compounds, described in a study published January 14th in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Beata Jastrzebska from Case Western Reserve University, US, and colleagues, were identified using a virtual screening approach.

In retinitis pigmentosa, the retina protein rhodopsin is often misfolded due to genetic mutations, causing retinal cells to die off and leading to progressive blindness. Small molecules to correct rhodopsin folding are urgently needed to treat the estimated 100,000 ...

Following a 2005 policy, episiotomy rates have reduced in France without an overall increase in anal sphincter injuries during labor, with more research needed to confirm the safest rate of episiotomi

2025-01-14

Following a 2005 policy, episiotomy rates have reduced in France without an overall increase in anal sphincter injuries during labor, with more research needed to confirm the safest rate of episiotomies and the risks to specific subgroups

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Medicine: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004501

Article title: Episiotomies and obstetric anal sphincter injuries following a restrictive episiotomy policy in France: An analysis of the 2010, 2016, and 2021 National Perinatal Surveys

Author countries: France, Switzerland

Funding: ...

Rats anticipate location of food-guarding robots when foraging

2025-01-14

Researchers find that rats create neurological maps of places to avoid after experiencing a threat and think about these locations when exhibiting worry-related behaviors. These findings—which A. David Redish of the University of Minnesota, US, and colleagues presented in the open-access journal PLOS Biology on January 14th—may provide insight into the neuroscience of common psychological conditions like anxiety.

There are many theories as to why people experience anxiety. One is that anxiety is associated with a psychological phenomenon called “approach-avoidance conflict,” where ...

The American Association for Anatomy announces their Highest Distinctions of 2025

2025-01-14

ROCKVILLE, MD—January 14, 2025—The American Association for Anatomy (AAA) is thrilled to announce the recipients of their 2025 Spring Awards. Each awardee will be formally recognized at the Anatomy Connected 2025 Closing Awards Ceremony on March 31, in Portland, Oregon.

The Spring Awards include the three highest distinctions awarded by AAA: the Henry Gray Scientific Award, the A.J. Ladman Exemplary Service Award, and the Henry Gray Distinguished Educator Award. The winners of these awards, along with the others on this list, are gathered through a nomination process conducted by their peers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New research finds heart health benefits in combining mango and avocado daily

New research finds peanut butter consumption builds muscle power in older adults

Study identifies aging-associated mitochondrial circular RNAs

The brain’s primitive ‘fear center’ is actually a sophisticated mediator

Brain Healthy Campus Collaborative announces winner of first-ever Brain Health Prize

Tokyo Bay’s night lights reveal hidden boundaries between species

As worms and jellyfish wriggle, new AI tools track their neurons

ATG14 identified as a central guardian against liver injury and fibrosis

Research identifies blind spots in AI medical triage

$9M for exploring the fundamental limits of entangled quantum sensor networks

Study shows marine plastic pollution alters octopus predator-prey encounters

Night lights can structure ecosystems

A parasitic origin for the ribosome?

A gold-standard survey of the American mood

Tool for identifying children at risk of speech disorders

How Japanese medical trainees view artificial intelligence in medicine

MambaAlign fusion framework for detecting defects missed by inspection systems

Children born with upper limb difference show the incredible adaptability of the young brain

How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

Fast-paced lives demand faster vision: ecology shapes how “quickly” animals see time

Global warming and heat stress risk close in on the Tour de France

New technology reveals hidden DNA scaffolding built before life ‘switches on’

New study reveals early healthy eating shapes lifelong brain health

Trashing cancer’s ‘undruggable’ proteins

Industrial research labs were invented in Europe but made the U.S. a tech superpower

Enzymes work as Maxwell's demon by using memory stored as motion

Methane’s missing emissions: The underestimated impact of small sources

Beating cancer by eating cancer

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

[Press-News.org] Putting a lid on excess cholesterol to halt bladder cancer cell growthSalk researchers discover novel targets for bladder cancer therapeutics and demonstrate that a new combination of existing drugs, including statins, blocks tumor growth in mice