(Press-News.org) Octopus arms move with incredible dexterity, bending, twisting, and curling with nearly infinite degrees of freedom. New research from the University of Chicago revealed that the nervous system circuitry that controls arm movement in octopuses is segmented, giving these extraordinary creatures precise control across all eight arms and hundreds of suckers to explore their environment, grasp objects, and capture prey.

“If you're going to have a nervous system that's controlling such dynamic movement, that's a good way to set it up,” said Clifton Ragsdale, PhD, Professor of Neurobiology at UChicago and senior author of the study. “We think it’s a feature that specifically evolved in soft-bodied cephalopods with suckers to carry out these worm-like movements.”

The study, “Neuronal segmentation in cephalopod arms,” was published January 15, 2025, in Nature Communications.

Each octopus arm has a massive nervous system, with more neurons combined across the eight arms than in the animal’s brain. These neurons are concentrated in a large axial nerve cord (ANC), which snakes back and forth as it travels down the arm, every bend forming an enlargement over each sucker.

Cassady Olson, a graduate student in Computational Neuroscience who led the study, wanted to analyze the structure of the ANC and its connections to musculature in the arms of the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides), a small species native to the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California. She and her co-author Grace Schulz, a graduate student in Development, Regeneration and Stem Cell Biology, were trying to look at thin, circular cross-sections of the arms under a microscope, but the samples kept falling off the slides. They tried lengthwise strips of the arms and had better luck, which led to an unexpected discovery.

Using cellular markers and imaging tools to trace the structure and connections from the ANC, they saw that neuronal cell bodies were packed into columns that formed segments, like a corrugated pipe. These segments are separated by gaps called septa, where nerves and blood vessels exit to nearby muscles. Nerves from multiple segments connect to different regions of muscles, suggesting the segments work together to control movement.

“Thinking about this from a modeling perspective, the best way to set up a control system for this very long, flexible arm would be to divide it into segments,” Olson said. “There has to be some sort of communication between the segments, which you can imagine would help smooth out the movements.”

Nerves for the suckers also exited from the ANC through these septa, systematically connecting to the outer edge of each sucker. This indicates that the nervous system sets up a spatial, or topographical, map of each sucker. Octopuses can move and change the shape of their suckers independently. The suckers are also packed with sensory receptors that allow the octopus to taste and smell things that they touch—like combining a hand with a tongue and a nose. The researchers believe the “suckeroptopy,” as they called the map, facilitates this complex sensory-motor ability.

To see if this kind of structure is common to other soft-bodied cephalopods, Olson also studied longfin inshore squid (Doryteuthis pealeii), which are common in the Atlantic Ocean. These squid have eight arms with muscles and suckers like an octopus, plus two tentacles. The tentacles have a long stalk with no suckers, with a club at the end that does have suckers. While hunting, the squid can shoot the tentacles out and grab prey with the sucker-equipped clubs.

Using the same process to study long strips of the squid tentacles, Olson saw that the ANC in the stalks with no suckers are not segmented, but the clubs at the end are segmented the same way as the octopus. This suggests that a segmented ANC is specifically built for controlling any type of dexterous, sucker-laden appendage in cephalopods. The squid tentacle clubs have fewer segments per sucker, however, likely because they do not use the suckers for sensation the same way octopuses do. Squid rely more on their vision to hunt in the open water, whereas octopuses prowl the ocean floor and use their sensitive arms as tools for exploration.

While octopuses and squid diverged from each other more than 270 million years ago, the commonalities in how they control parts of their appendages with suckers—and differences in the parts that don’t—show how evolution always manages to find the best solution.

“Organisms with these sucker-laden appendages that have worm-like movements need the right kind of nervous system,” Ragsdale said. “Different cephalopods have come up with a segmental structure, the details of which vary according to the demands of their environments and the pressures of hundreds of millions of years of evolution.”

END

Octopus arms have segmented nervous systems to power extraordinary movements

The large nerve cord running down each octopus arm is separated into segments, giving it precise control over movements and creating a spatial map of its suckers.

2025-01-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Protein shapes can help untangle life’s ancient history

2025-01-15

The three-dimensional shape of a protein can be used to resolve deep, ancient evolutionary relationships in the tree of life, according to a study in Nature Communications.

It is the first time researchers use data from protein shapes and combine it with data from genomic sequences to improve the reliability of evolutionary trees, a critical resource used by the scientific community for understanding the history of life, monitor the spread of pathogens or create new treatments for disease.

Crucially, the approach works even with the ...

Memory systems in the brain drive food cravings that could influence body weight

2025-01-15

PHILADELPHIA, PA (January 15, 2025) - Can memory influence what and how much we eat? A groundbreaking Monell Chemical Senses Center study, which links food memory to overeating, answered that question with a resounding “Yes.” Led by Monell Associate Member Guillaume de Lartigue, PhD, the research team identified, for the first time, the brain’s food-specific memory system and its direct role in overeating and diet-induced obesity.

Published in Nature Metabolism, they describe a specific population of neurons in the mouse brain that encode memories for sugar and fat, profoundly impacting food intake and body ...

Indigenous students face cumbersome barriers to attaining post-secondary education

2025-01-15

Indigenous students identified inadequate funding as a major barrier to completing post-secondary education according to a new study published in AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples.

The study surveyed Indigenous university students at Algoma University. The students, who identified as either First Nations or Métis, reported that they required multiple sources of funding, including government student loans and personal savings, to afford their post-secondary education. About two-thirds (69%) of students received funding for their education from First Nations sources, including funding from federal programs for Indigenous students.

“This ...

Not all Hot Jupiters orbit solo

2025-01-15

Hot Jupiters are giant planets initially known to orbit alone close to their star. During their migration towards their star, these planets were thought to accrete or eject any other planets present. However, this paradigm has been overturned by recent observations, and the final blow could come from a new study led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE). A team including the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS, the Universities of Bern (UNIBE) and Zurich (UZH) and several foreign universities has just announced the existence of a planetary system, WASP-132, ...

Study shows connection between childhood maltreatment and disease in later life

2025-01-15

University of Birmingham venture Dexter has demonstrated the power of its Dexter software platform in a study showing that people whose childhoods featured abuse, neglect or domestic abuse carry a significantly increased risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis in later life.

The starting point for the recently published study was a database of over 16 million Electronic Health Records, from which the Dexter software defined a cohort, one arm that was exposed to childhood maltreatment, and one arm that was not.

The software then checked the records over a 26-year period ...

Discovery of two planets sheds new light on the formation of planetary systems

2025-01-15

The discovery of two new planets beyond our solar system by a team of astronomers from The University of Warwick and the University of Geneva (UNIGE), is challenging scientific understanding of how planetary systems form.

The existence of these two exoplanets - an inner super-Earth and an outer icy giant planet - within the WASP-132 system is overturning accepted paradigms of how ‘hot Jupiter’ planetary systems form and evolve.

Hot Jupiters are planets with masses similar to those of Jupiter, but which orbit closer to their star than Mercury orbits the Sun. There is not enough gas and dust for these giant planets to form ...

New West Health-Gallup survey finds incoming Trump administration faces high public skepticism over plans to lower healthcare costs

2025-01-15

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Weddnesday, Jan. 15, 2025 — Nearly half of Americans (46%) think the country is headed in the wrong direction when it comes to the incoming president’s policies to lower healthcare costs, while 31% say it’s on the right track, according to the latest West Health-Gallup survey released today.

When viewed through a political lens, only Republicans are more positive than negative about the future of healthcare costs under the Trump administration; nearly three-quarters (73%) think the incoming administration’s healthcare policies are headed in the right direction. In contrast, 24% of independents and 3% of Democrats say the same. Democrats ...

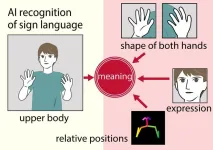

Reading signs: New method improves AI translation of sign language

2025-01-15

Sign languages have been developed by nations around the world to fit the local communication style, and each language consists of thousands of signs. This has made sign languages difficult to learn and understand. Using artificial intelligence to automatically translate the signs into words, known as word-level sign language recognition, has now gained a boost in accuracy through the work of an Osaka Metropolitan University-led research group.

Previous research methods have been focused on capturing information about the signer’s ...

Over 97 million US residents exposed to unregulated contaminants in their drinking water

2025-01-15

Nearly a third of people in the U.S. have been exposed to unregulated contaminants in their drinking water that could impact their health, according to a new analysis by scientists at Silent Spring Institute. What’s more, Hispanic and Black residents are more likely than other groups to have unsafe levels of contaminants in their drinking water and are more likely to live near pollution sources.

The findings, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, add to growing concern about the quality of drinking water in the United States and the disproportionate impact of contamination ...

New large-scale study suggests no link between common brain malignancy and hormone therapy

2025-01-15

CLEVELAND, Ohio (Jan 15, 2025)–It’s not easy being a woman. Just look at the statistics. Women are more likely to have such debilitating conditions as osteoporosis, migraines, Alzheimer disease, depression, multiple sclerosis, and brain tumors. Sex hormones are often blamed. However, a new study suggests no link between hormone therapy (HT) and common brain tumors known as gliomas. Results of the study are published online today in Menopause, the journal of The Menopause Society.

The debate over the risks and benefits ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

[Press-News.org] Octopus arms have segmented nervous systems to power extraordinary movementsThe large nerve cord running down each octopus arm is separated into segments, giving it precise control over movements and creating a spatial map of its suckers.